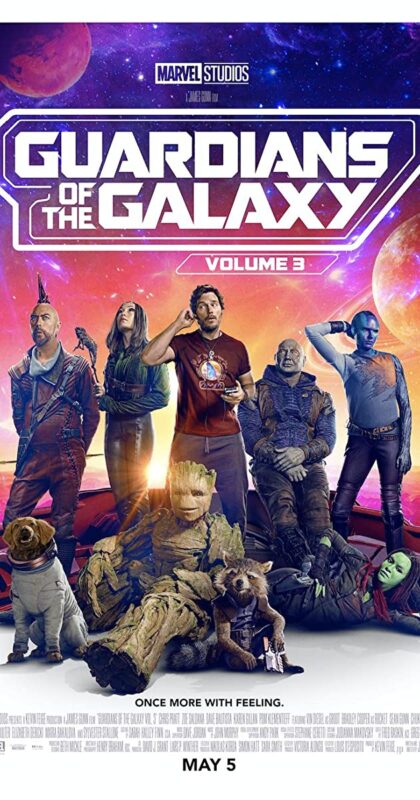

This summer’s installment of “If you don’t teach your kids theology, Marvel Studios will” comes in the form of Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3. Sure, it’s not a Scorsesian theological treatise. At times it felt very much like a roller coaster ride–an impression helped along by the fact that just a month ago I was riding an actual Guardians of the Galaxy coaster with filmed story elements featuring the same cast. But every now and again, this technicolor space opera takes a breath between virtuosic cadenzas of violence and Zune tunes for a melodramatic musing. The question weighty enough to pull away from the black hole of bombast: What does a creator owe its creation?

In case you missed the first two volumes, the Guardians are a found family of alien assassins and Terran thieves whose moral sextants sometimes land them in a position to prevent existential problems. Within their ranks is Rocket, a technically gifted master of mayhem who is adamantly not a talking raccoon no matter how much you might think otherwise. After hinting at a tragic backstory across two Guardians films plus appearances in a pair of Avengers events and last summer’s Thor installment, Marvel finally makes us privy to his past. His scars and technological implants already heavily implied a brush with an unscrupulous scientist. That scientist turns out to be a character known as High Evolutionary and the experiments that left Rocket scarred were part of a sequence intended to yield a perfect species.

If the film is a roller coaster, that information is the chain lift that carries the Guardians and the audience to the top of the first hill. From there we are shuttled to some frankly silly places, pulled along by the weight of what has been done to Rocket. While we enjoy a few laughs, he wonders what purpose any of it could serve beyond the pain. The closest thing to an answer he is given is a distinction between the hands that made him–the High Evolutionary’s–and the hands that guide those hands.

Who those hands belong to remains a mystery. The other ‘g’ word gets thrown around a fair bit in this film and many other Marvel movies. We are told some of High Evolutionary’s creations worship him as a god. The Guardians have their headquarters in the head of a dead Celestial or “space god” (we have previously learned that the Eternals consider Celestials their gods). Thor: Love and Thunder where we last saw Rocket & friends on the big screen showed us that all the Earthly pantheons and many alien ones as well exist alongside the Asgardians (who themselves were first introduced as advanced aliens who merely inspired Norse beliefs but who have drifted towards a status more akin to actual deities). Maybe it’s even a sly reference to Marvel Studios boss Kevin Feige–or his in-universe robotic avatar K.E.V.I.N.

Any of those could be the answer, although just as likely they all cancel each other out. Plenty of epic poems and plays and operas (and one overlong sitcom opening credits) have already illustrated the potential pitfalls of pantheons with their competing agendas and all-too-human character flaws. Wouldn’t a singular vision be preferable? That’s certainly the argument across much of the Old Testament. Marvel Comics have also entertained the possibility of monotheism, if for no other reason than to stay onside with the cultural context of their audience.

Personally, I am less curious about the ‘who’ and more curious as to whether that one step of removal (“the hands that guide those hands”) actually affords any absolution. We are clearly meant to understand that what the High Evolutionary did caused harm and reduced Rocket to a mere research object for whom empathy was neither warranted nor possible. There is no question this is reprehensible. But what if, in some round about way, it served some higher purpose? If the guiding hands were working toward that higher purpose and if there were no other way to achieve it, would that make them less guilty?

Voltaire struggled with that line of thinking, and if I’m honest, so do I. Yes, people respond to adversity and suffering by making positive and constructive choices all the time, and that is commendable. Psychologically, looking for silver linings seems to be a healthy approach. But we’re not talking about how to cope with the reality of specific difficulties, we’re talking in the abstract about whether they are actually necessary. While we can never actually explore all of the counterfactuals to answer that question, I can understand why the question comes up.

Now, I would not be me if I didn’t mention that the High Evolutionary should really be called the High Engineer. There is very little evolutionary about the processes he employs in pursuit of what he deems to be perfect. Yes, it is an iterative process, but there is no continuity from one iteration to the next. And while it might appear he is iterating towards the fittest species, even a casual glance around should reveal that in reality the fittest aren’t confined to a single species. The High Evolutionary would seem to have a roller coaster model of biology: there is a single highest point and a single path to reach it. But evolution only works because there are in fact many paths to the same biological outcome. And there are many equally viable outcomes, as demonstrated by the diversity of species. Even further, the “tracks” are dynamic; what works today may not work so well tomorrow, which is what makes evolvability advantageous in the first place. In short, the idea of a single, fixed perfect species makes very little evolutionary (or ecological) sense.

For story purposes, that’s perfectly fine. I’m not pointing that out to critique the movie (which is really just reiterating High Evolutionary’s schtick from the comics). Instead, I am wondering how much of the usual theodicy discussion involves a roller coaster-like view of reality. Maybe there isn’t a single best of all possible worlds, and a single way to realize it. Maybe the guiding hands didn’t lay a single set of tracks. Maybe the guiding hands are waving us on, beckoning us forward, pointing out problems and picking us up when we trip over them anyway. Maybe those are the hands of Voltaire’s gardener. I didn’t say it was a new answer. After all, there is nothing new under the sun–except maybe a talking raccoon.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply