Religious nationalism is not a new phenomenon. In this two part series (Part One here) GFM staff minister Bill Nelson will explore the elements of religious nationalism and how the book of Jonah serves as a call to repentance and restoration.

A bewildering array of images emerged amid the chaos of the Capitol riots on January 6, 2021. Rioters carried wooden crosses and erected wooden gallows with hanging nooses. Insurrectionists carried Confederate flags, first flown by states that supported secession from the United States and the continuation of slavery. Others paraded Christian flags alongside the Confederate flag bearers. Such toxic mixtures of racism and Christendom are also found in Christian social studies textbooks. As shown in Part 1, mainstream Christian curricula teach history through an ethnocentric lens, mirroring and providing a religious covering for white supremacy.

To the toxic mix of racism and religion, I add American exceptionalism. Racism, religion, and American exceptionalism provide the foundational pillars of Christian nationalism, the belief that America is and must remain a uniquely virtuous “Christian nation.”

Christian nationalism is an idolatrous ideology that distorts our witness for Christ and undermines the Gospel. The Old Testament book of Jonah speaks as a corrective call to repentance and a hopeful message of restoration.

American Exceptionalism

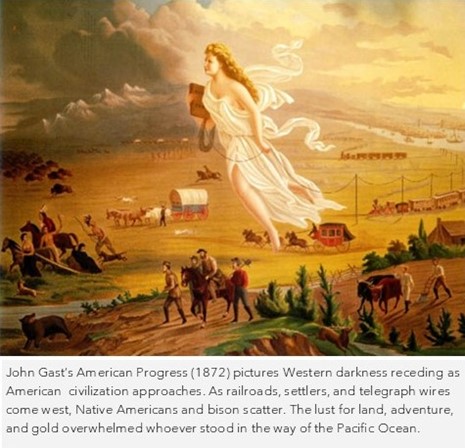

American exceptionalism proposes that God uniquely and providentially chose the US for a unique mission to transform the world. Christian curricula’s pseudo-historical narratives cast the settlers, founders, and leaders of European descent in early America heroically as God’s new chosen people. They idealize the United States’ past “golden age.” An Abeka US history textbook opens by stating, “God in His wisdom allowed America to remain hidden until the Modern Age [brought] important changes that would profoundly affect the course of American history.”[i]

Of course, First Nations peoples occupied the” hidden land” for millennia until White European settlers drove them out. America’s colonists stole livestock, burned, and looted houses and towns, and committed mass murder. They left a legacy of stolen lands, broken treaties, massacres, boarding schools, and forced assimilation. Their lust for land and power conflicted with America’s proclaimed moral superiority.

Christian textbooks ignore the brutal mistreatment and genocide of Native communities. “Certainly, the colonists’ harsh treatment of Native Americans has no part of this [American] heroic tale,” writes Kathleen Wellman, author of Hijacking History: How the Christian Right Teaches History and Why It Matters.[ii]

Instead, Christian curricula call Jesus’ followers to arise and lead the way back to America’s “golden age of moral and spiritual purity.” Abeka states, “As salt and light, Christians must strive to hold back the evil and preserve the good in America.”[iii] A Bob Jones University textbook adds, “At no time in American history has there been a greater need for such spiritual leaders [as the U.S. patriots at Valley Forge and Stonewall Jackson, the Confederate Civil War general] driven by the demands of Calvary.”[iv]

Christian textbooks claim “that the United States was founded as a Christian nation and that Christianity should have a privileged public position, […] that America is exceptional and its history entirely admirable,” says Dr. Wellman, “[Their] positions are widely diffused in school board meetings, on the floors of state legislatures, in the sermons of megachurches, and the speeches of political candidates.”

“Our Nation, Not Theirs”

In events leading up to the January 6 Capitol riots, Christian nationalism advocates used historical narratives resembling those in Christian textbooks to call God’s people to arms. Promoters incited Christian “patriots” to fight the outside invaders —socialists, secularists, Muslims, and Black radicals. Crusading “prophets” charged the “Lord’s mighty armies” to restore a mythical version of America to its rightful owners: those “right for God.”[v]

Jonah and Religious Nationalism

Jonah embraced similarly toxic views of religious nationalism. As a court prophet within evil King Jeroboam’s militaristic administration, Jonah spoke of God restoring the northern kingdom of Israel’s fortunes and lands (2 Kings 14:23-27). Jonah personified how the Israelites perceived themselves as exceptional. They had a special covenant with God that “inferior others” lacked.

The Lord connects Israel’s great calling (“you only have I chosen”) with the grave consequences of their unfaithfulness (“therefore I will punish you”) (Am 3:2). Amos, roughly Jonah’s contemporary, delivers scathing accusations and judgments against Israel’s northern kingdom three times longer and more intense than those against seven of Israel’s enemies (Am. 3-6; cf. 1:3-2:6). The Lord passionately calls Israel to repentance (Am. 5:14-15).

The book of Jonah similarly prompts God’s people to repentance. The narrator of Jonah’s story casts “pagans,” various animals, and a plant as Jonah’s literary foils. They highlight the prophet’s ridiculous attitudes, inviting critique of Jonah and correcting those he represents.

Jonah’s first self-identifying words: “I’m a Hebrew” (1:9), suggest his nationalistic pride. Jonah frames himself as religiously superior to “those who cling to worthless idols” (2:8-9).

In Nineveh, the Lord’s compassion towards the humbled and repentant Ninevites ignites Jonah’s outrage. His morbid hot anger mirrors the blazing desert sun.

The Lord prods Jonah to self-examination, trying to help him comprehend unsettling truths. He provides Jonah a shade plant “to ease his discomfort (ra’ah)” (4:6). The narrator puns on the word (ra’ah) for an ironic twist.[vi] The term refers to Jonah’s physical discomfort and his inner evil. Subsequent events show that God intends to deliver Jonah from his inner evil.

The Lord appoints a worm to devour the shade plant, re-exposing Jonah to the scorching sun. He also adds a second layer of misery —hot desert winds.

Jonah’s meltdown resumes. His exuberant rejoicing over his shade plant reverts into a bitter tirade and a second death wish. He feels entitled to a plant he neither planted nor caused to grow. He pities his soulless shade plant, but not Ninevite souls. Jonah cares only for himself.

Jonah’s story ends with him sulking, morbidly peering down on the city of Nineveh. But he is not alone. The Lord continues relentlessly pursuing His wayward prophet.

Should I Not Have Concern?

God appeals, “You [Jonah] have been concerned about this plant, though you did not tend it or make it grow. It sprang up overnight and died overnight. And should I not have concern for the great city of Nineveh in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left—and also many animals?” (4:10-11).

The Lord’s rhetorical question to Jonah orients us toward self-awareness, seeing others from God’s perspective, and embracing His universal concern for all peoples.

We join in God’s restoration of our hearts and world as we mourn losses, ask the Lord to show us our complicity, confess sin, and pray for His just intervention. Dr. Soong-Chan Rah shows how lament can shape us into better Christ-followers, advocates, reformers, and friends, in Prophetic Lament: An Interview (5-minute read).

The Gospel calls us to look beyond our communal and national borders to engage our broken world. We cannot ignore urban poverty and the rights of workers who provide us with cheap goods from abroad. Nor can we ignore global warming because we have air conditioning and environmental exploitation that does not affect our neighborhood. And we cannot turn our backs on impoverished refugees. Jesus identifies himself with the “foreigner,” warning those who fail to recognize him, “I was a stranger, and you did not welcome me in” (Mt. 25:43).

White Christian Nationalism conflates white supremacy and Jesus’ teachings with delusional patriotism. In The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism, Georgetown University Professor Paul Miller clarifies what Christian nationalism is and explains its dangers. Dr. Miller also equips us to address these issues in our public witness and within the church. Christians Against Christian Nationalism also provides resources for understanding and communal engagement.

Join the Emerging Scholars Network and Paul D. Miller, author of The Religion of American Greatness for a discussion of Christian nationalism. This live conversation will be on September 15, 2022 at 12 pm ET. Sign up at https://tinyurl.com/ESNAmericanGreatness.

[i] Michael R. Lowman, George Thompson and Kurt Grussendorf, United States History in Christian Perspective: Heritage of Freedom (Pensacola, FL: Abeka, 1996), 678.

[ii] Wellman, Kathleen. Hijacking History: How the Christian Right Teaches History and Why It Matters, (Oxford University Press, 2021), 163.

[iii] Abeka, US, 5.

[iv] Timothy Keesee and Mark Sidwell, United States History (Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University Press, 2001), 656.

[v] For example, at the December 12 Jericho March’s “Let the Church ROAR” event, the blowing of shofars echoed the summoning of an invasion. Bishop Leon Benjamin pronounced, “We are here in the mighty name of Jesus today to declare that every Jericho wall must come down!” Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano prayed, “As in the time of Joshua, […] break down the walls of the City of darkness, granting victory to those who serve under Thy holy banner.”

[vi] The NIV captures the term’s broad semantic range translating (ra’ah) in Jonah variously as “wickedness” (1:2), “calamity” (1:7), “trouble” (1:8), “evil” (3:8), “evil” and “destruction” (3:10), “seemed very wrong,” (4:1), and “discomfort” (4:6). Evil (ra’ah) now applies to Jonah as it did previously to the Ninevites (Jon. 4:6; cf. 1:2; 3:8, 10).

God has privileged Bill Nelson to represent Him among students and scholars gathered from over 50 nations at Johns Hopkins University over the past 25 years. Bill is an ordained minister through the Evangelical Free Church of America (EFCA), having received his theological and ministry training at Dallas and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminaries. He and his wife Michele enjoy hiking in the mountains and other activities with friends and family, including their three grown children.

Leave a Reply