Religious nationalism is not a new phenomenon. In this two part series GFM staff minister Bill Nelson will explore the elements of religious nationalism and how the book of Jonah serves as a call to repentance and restoration.

As a new Christian fresh out of college, I taught at a private Christian school with godly and dedicated colleagues. We pledged our allegiance to the American and Christian flags and the Holy Bible alongside our students each school day. Our school used mainstream Christian curricula, including social studies textbooks that advanced nativist, ahistorical narratives. Their biases continue to misrepresent Jesus and distort His kingdom.

In Part 1 of our two-part series, I show how Christendom too often provides religious cover for bigotry and prejudice, reflected by Christian textbooks’ teaching of history through an ethnocentric lens. Part 2 explains how these textbooks’ dysfunctional narratives portray and lend credibility to Christian nationalism, a toxic combination of racism, religion, and politics. Throughout our series, the Old Testament book of Jonah speaks as a corrective call to repentance and a hopeful message of restoration.

Heretical Othering

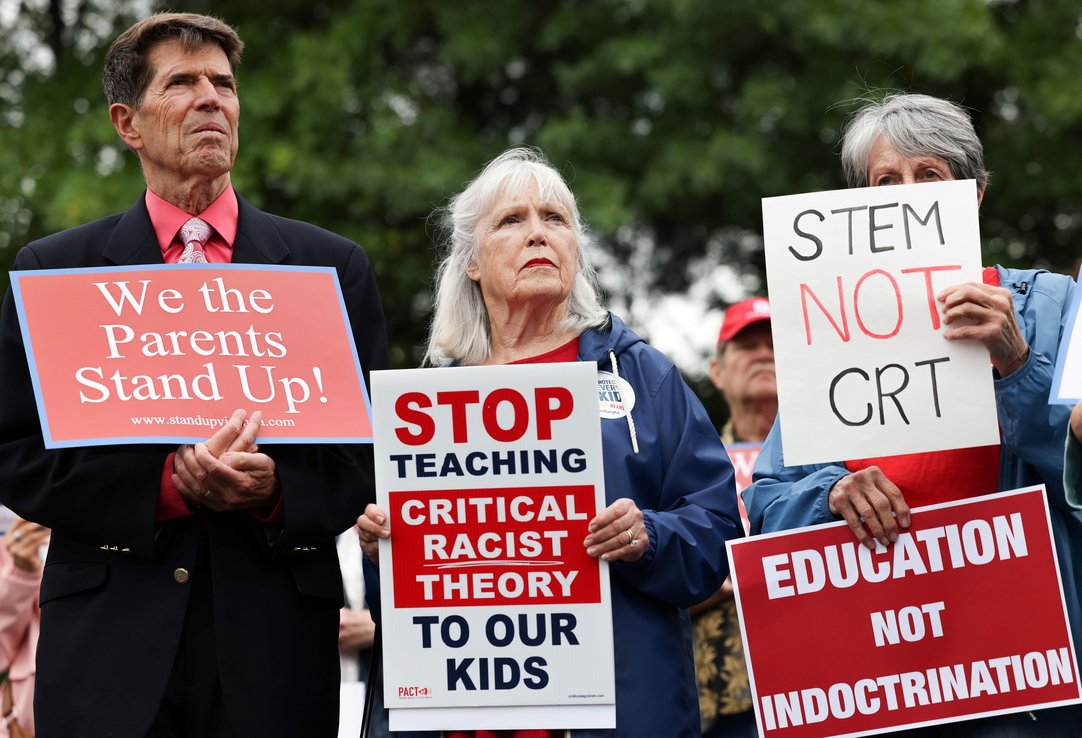

Political competition in America is “a poisonous cocktail of othering, aversion, and moralization,” reads the subtitle of the article, “Political Sectarianism in America,” recently published by fifteen prominent scholars in Science magazine. “Othering” pits the worthy “us” against the undeserving “them.” Tribal members weaponize words in tropes, inciting derision and contempt within political arenas, media spaces, school board meetings, and Christian communities. Some frame fellow Christ-followers as “heretical others” for their stances on social issues.[1]

In November 2021, alarmed Grove City College parents appealed to GCC’s president, outlining their perceptions of Critical Race Theory (CRT) as “a destructive and profoundly unbiblical worldview, threatening the academic and spiritual foundations that make the school distinctly Christian.” GCC’s student body is 92 percent white, with one black faculty member. Many of GCC’s undergraduates come from private Christian high schools or were homeschooled.

The self-identified “Save GCC from CRT” petitioners cited NYT’s best-selling author, Jemar Tisby’s chapel message a year earlier as an example of CRT’s pervasive spread. In his 21-minute talk, Dr. Tisby, a Reformed Theological Seminary graduate, charged GCC students to pursue racial justice, pairing the Old Testament book of Esther with quotes from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Responding to the petitioners’ concerns, GCC’s Trustees called for an internal investigation of “creeping wokeness.” In May 2022, the Trustees accepted and adopted the committee’s report, which libeled Tisby and his racial justice work and called GCC’s chapel invitation to him “a mistake.”

Tisby countered by denying that he is a Critical Race Theorist “out of respect for the scholars and experts who have devoted years […] to learning about and developing this theory utilized most often in legal studies.” He suggested that the real issue with his chapel talk “was not how I spoke about racism but that I spoke about it at all.”

GCC president Paul McNulty recently lamented, “I worry that our polarization is extended to the point where I don’t know how we come out of it.”

Dysfunctional Narrative Othering

The recent conflict at GCC reflects the current national debate. Since January 2021, 19 states have passed laws or rules restricting how race or racism can be addressed in classrooms.[2] College campuses are now in legislators’ crosshairs.

With public schools on the defensive and boosted by the June 2022 Supreme Court ruling that backs the use of tax dollars at religious schools, K-12 Christian schools are booming. Many use curricula that malign justice advocates and dismiss systemic injustices.[3]

Enslaved people in the antebellum South constituted about one-third of the southern population. They suffered rape, molestation, torture, murder, theft, and kidnapping, among other evils. Slave families were often split up through trade, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

Mainstream Christian textbooks whitewash slavery, says John Wilsey, a Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary church history professor. With one publisher, “the problems of slavery were social and economic, not moral,” according to Dr. Wisley.[4] ”State rights, not slavery, was the central issue of the American Civil War,” reads the text from another publisher’s book.[5] A third suggests, “If masters had treated their slaves ethically, and if slaves had submitted humbly, according to biblical standards, American slavery could have survived.”[6]

Abeka’s textbooks are the most popular, with millions of users since 1972, including over 2.5 million homeschoolers in 2020 and more than 1 million Christian school students in 2017. Their sixth-grade American history textbook suggests that Martin Luther King facilitated violence. “Dr. King’s teaching that people should break the law in nonviolent ways to bring about change opened the door to other kinds of lawbreaking,” the text reads. “As violence began to take over, Dr. King found he could not control all the radical groups.”[7]

Like Dr. King, Gandhi led a nonviolent resistance movement bringing freedom to the oppressed. Gandhi freely credited Jesus for his life principles of forgiveness, love for enemies, and returning evil with good. Abeka alleges that Gandhi was corrupted by “fanatical devotion to Hinduism” and exposure to “Fabian socialism” in British universities.[8]

Abeka also claims that Nelson Mandela was “a Marxist agitator” who led South Africa to ”communist tyranny and radical affirmative action.”[9] As South Africa’s first black president, Mandela dismantled apartheid and brought healing to the divided nation.

In modern history, Abeka attributes vandalized and neglected housing within inner cities to a “lack of homeowner’s pride.” Their textbooks also criticize President Barack Obama for escalating racial tensions and fault Black Lives Matters groups for inciting racial strife and conflict between police and communities with “divisive rhetoric.” Abeka fails to mention systemic and institutional factors contributing to urban poverty and unrest.

Other contemporary Christian curricula targets include Muslims, Native Americans, Atheists, environmentalists, the LGBTQ community, and feminists.

Mainstream Christian curricula frame ethnic and religious minorities and the non-religious as “inferior others.” Their narratives minimize systemic injustices and marginalize voices of change.

Majority Church Othering

Christian textbooks mirror how American Christendom too often sacrifices ethnic justice for (white) national unity. Christians of color say that “White Christians, by their actions, seem to favor being white over being Christian,” according to Sociologist Michael Emerson based on intensive nationwide surveys over the past three years.[10] The CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, Dr. Robert Jones, argues that Christendom is the dominant cultural power protecting white supremacy.[11]

Generation Z (those born between 1995-2010) is the most unchurched in American history. Many young people believe the church does not share their social justice concerns.[12] Sadly, some are exiting the church to search for Jesus and re-examine church teachings.[13]

Jonah and Othering

Amid a sifting and reckoning within American churches, the story of Jonah speaks powerfully as a corrective call to repentance and a hopeful message of restoration.

As a court prophet within evil King Jeroboam II’s administration, Jonah proclaims the Lord’s restoration of ancient Israel’s fortunes and lands.[14] During Jeroboam’s 40-year reign, Israel’s northern kingdom experiences unprecedented prosperity.

The prophet Amos warns the prosperous nation of looming catastrophe and imminent exile.[15] “Woe to you who […] “turn justice into bitterness and cast righteousness to the ground” (Am. 5:7), the Lord declares to Israel’s wealthy and complacent upper-class, “Are not you Israelites the same to me as the Cushites?” (Am. 9:7). Israelites considered the Cushites as those living at the world’s end. The Lord underscores that His concern extends equally to everyone.

To move God’s people to repentance, Jonah’s narrator casts “pagans,” various animals, and a plant as Jonah’s literary foils. They highlight the prophet’s ridiculous attitudes, inviting his critique and correction of those he represents.

God tells Jonah to go to Nineveh; Jonah runs to hide.

God relentlessly pursues His runaway prophet in scenes full of irony and satire.

The Lord initially intervenes through a life-threatening storm at sea. The desperate “pagan” ship’s captain confronts Jonah, “‘How can you sleep? Get up and call on your god!” (1:6).

Despite sleeping amid a crisis onboard a ship far from where God calls him, Jonah presumptuously asserts, “I fear the Lord” (1:9).

God rescues His sinking prophet in the depths of the sea through a great fish.

From inside the fish, Jonah frames himself as superior to “those who cling to worthless idols” (2:8-9).[16] Ironically, the “pagans” Jonah compares himself to “fear the Lord exceedingly” (1:16; cf. 3:6-9).

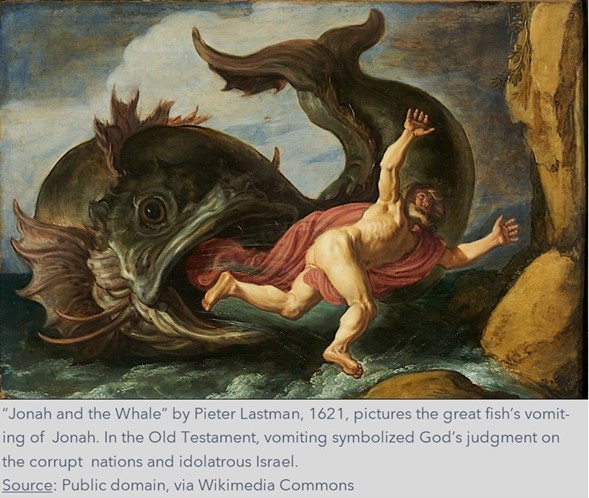

The Great Fish cannot stomach Jonah’s pious self-righteousness. Sickened by his hypocritical piety, it vomits Jonah onto dry land in immediate obedience to God’s command.[17]

Jonah reluctantly obeys God’s second call to his unwanted urban assignment. Counter to God’s intentions, he still desperately wants Nineveh, “the city of bloodshed” (Nah. 3:1) obliterated.[18]

Jonah’s attitudes personify Israel’s. Thirty years after Jeroboam II, their prosperous kingdom becomes an Assyrian province.[19] Israel’s elite march first in the line of captives.[20] The Promised Land vomits them out just as it vomited the wicked Canaanites before them.[21]

Jesus and Othering

Similarly, Jesus warns the Laodicean church: “I am going to vomit you out of my mouth” (Rev. 3:16).[22] Jesus exposes the materially wealthy, socially complacent, and spiritually presumptuous Laodiceans as “wretched, pitiful, poor, blind and naked” (Rev. 3:17).[23]

Jonah and the Laodicean church speak to our complacency. “Evangelical silence reinforces the dominant cultural narrative, which says that Christians don’t care, that the message of Jesus aligns with xenophobia, and that if we want more racial justice in America, we need less Christianity,” says Dr. Robert Chao Romero, a Chicana/o and Asian American Studies professor at UCLA.[24] When we fail to seek justice, we abdicate our calling as signposts of Jesus’ kingdom.

Returning To Jesus

God sees, hears, and responds to brokenness. Jesus sends us in community to bring shalom (God’s peace). Shalom up-ends the systems of power that oppress. God calls us to seek justice for the violated and to be a voice for the voiceless.

We join the Holy Spirit in restoring the brokenness within us and our world by resting our hope and confidence in King Jesus. When Jesus returns, He will completely and permanently eradicate evil and injustice and renew us and all creation.

As we long for His coming, Jesus extends the same grace and patience He extended to the Laodicean church (and Jonah, as we’ll see in Part 2). Longing for a relationship, Jesus knocks at our door. He invites us to share an intimate meal with Him (Rev. 3:19-20). We open the door to Jesus’ intimate presence through our sincere repentance.

Confessional Prayer

Eternal God, our judge, and redeemer, we confess that we have tried to hide from you, for we have done wrong. We have lived for ourselves and turned from our neighbors. We have refused to bear the troubles of others. We have ignored the world’s pain and passed by the hungry, the poor, and the oppressed. O God, in your great mercy, forgive our sin and free us from selfishness, that we may choose your will and obey your commandments, through Jesus Christ our Savior. Amen. — Episcopal Book of Common Prayer

Resources

The Christian non-profit, Be the Bridge provides small group resources to equip us to move toward deeper relationships for understanding racial brokenness and systemic injustice.

Join the Emerging Scholars Network and Paul D. Miller, author of The Religion of American Greatness for a discussion of Christian nationalism. This live conversation will be on September 15, 2022 at 12 pm ET. Sign up at https://tinyurl.com/ESNAmericanGreatness.

[1] See here, here, and here for recent examples.

[2] Since January 2021, 42 states have introduced bills or taken other steps that would restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism, according to an Education Week analysis.

[3] Privileged people typically overlook systemic inequities that disproportionately impact minority communities. For example, the typical American White family has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times that of the typical Hispanic family. In 2018, black Americans represented 33% of the sentenced prison population, nearly triple their 12% share of the U.S. adult population. With just 4.2 % of the global population, the U.S. has roughly 25% of the world’s prison population.

[4] Wilsey, John D. American Exceptionalism and Civil Religion: Reassessing the History of an Idea. (InterVarsity Press, 2015), 209.

[5] Wilsey, 209.

[6] Wilsey, 208-211. In his survey of curricula published by three leading Christian textbook publishers, Dr. Wilsey notes that Omnibus III includes the essay “Slave Narratives,” co-authored by Douglas Wilson and G. Tyler Fisher, which argues that “slavery per see was not necessarily ethically wrong in part because Jesus did not preach against it.”

[7] Abeka, New World History, and Geography: In Christian Perspective (Pensacola, Fl: A Beka, 2018). 4th Ed

[8] Cited in Kathleen Wellman, Hijacking History: How the Christian Right Teaches History and Why It Matters, (Oxford University Press, 2021), 261.

[9] Abeka, World History And Cultures, 450.

[10] Dr. Emerson concludes: “Through extensive statistical analyses, we found that two-thirds of practicing white Christians are following, in effect, a religion of whiteness.”

[11] Jones, Robert. White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity (Simon & Schuster; Illustrated edition, 2020). PRRI polling measures both interpersonal and systemic racism. Dr. Jones concludes, “the more racist attitudes a person holds, the more likely they are to identify as a white Christian.” The correlation applies both to frequent (weekly or more) and infrequent (seldom or never) church attendees (175, 176).

[12] Barna researchers conclude that the church’s perceived absence of impact among 18-35-year-olds on issues of poverty and justice should be taken seriously.

[13] Among disaffiliated youth raised in religious homes, 69% say religion causes problems more than provides solutions.

[14] see 2 Kngs. 14:23-27

[15] Amos 4:1-3, 5:25-27, 6:1-14, and 7:7-17

[16] Jonah’s prayer in chapter 2 is a parody of lament. Parody imitates a current literary form with an inverted effect. The narrator includes Jonah’s use of the conventional lament Psalm language to expose his pious hypocrisy. Hosea also records a parody-like prayer in which the Lord responds with exasperation to His peoples’ empty words of superficial repentance (Hos. 6:3-7).

[17] While vomiting rescued Jonah from his underwater threat, it is also a biblical image of revulsion. God vomited out depraved Canaanites and rebellious Israelites from the Promised Land (Lev. 18:28; 20:20). Jesus warned the Church at Laodicea, “I am going to vomit you out of my mouth!” (Rev. 3:16). The Old Testament prophets used vomiting to picture God’s judgment upon the nations (Jer. 25:15, 27, 48:26; Is. 19:14, 28:8). – Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, InterVarsity Press, 1998, 919.

[18] Nineveh is called the “City of bloodshed” in Nahum 1:3.

[19] 2 Kngs.17:18, 20

[20] Am. 6:7

[21] Lev. 18:28; 20:20

[22] “Vomit” is the literal meaning of the Greek verb (emeÅ).

[23] The Laodiceans relied upon external water supplies sourced in hot and cold springs. While traveling through several miles of pipe, the water temperature moderated. In effect, Jesus says, if you were hot, you’d bring healing and comfort to the suffering. Likewise, you’d refresh and encourage those hurting if you were cold. Instead, you are lukewarm; you don’t do anyone any good.

[24] Labberton, Mark. Still Evangelical? (InterVarsity Press, 2018), Kindle Locations 1034-1036.

God has privileged Bill Nelson to represent Him among students and scholars gathered from over 50 nations at Johns Hopkins University over the past 25 years. Bill is an ordained minister through the Evangelical Free Church of America (EFCA), having received his theological and ministry training at Dallas and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminaries. He and his wife Michele enjoy hiking in the mountains and other activities with friends and family, including their three grown children.

Thank you Bill, for being willing to address this, and ESB for being willing to print it.

Thank you Gerald for your kind encouragement.