In honor of Women’s History Month, I’ve gathered for our readers the stories of a few of my favorite women saints. Sadly, even though we’ve been celebrating Women’s History Month in the U.S. since 1987, the Church remains of one of the few places in our society where the contributions of women have not been celebrated like they could be and should be.

One reason for the lack of acknowledgement and celebration of women’s achievements throughout Church history is that many of the Early Church Fathers embraced Greek ideas about the inferiority of women. This thinking also affected the medieval Scholastics[1] and the Reformers.[2] How could women be viewed as Christian role models or manage to achieve anything substantive for God when they were ontologically incapable of such things?

Another (and in our time, more influential) reason for this failure to commend the example and impact of women in the Church is a faulty and wooden reading of Paul in 1 Timothy 2:12-14, “I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent. For Adam was formed first, then Eve; and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor.” (NRSV)

The idea derived from this understanding of the text is that both the order of the creation of the sexes and the fact that Eve was deceived by Satan are reasons for forbidding women to teach men in the Church. Something about being created first puts men in a leadership role. The Satanic deception means that women have been shown to be constitutionally more gullible than men, and thus more easily deceived and unsuited for teaching.[3] This view of women as naïve or foolish subordinates has meant that the Church has failed to invite the contributions of women and to notice or celebrate the contributions our sisters have made.

Some of that is changing! Michael Bird, Australian professor of New Testament, has recently published a post in his Substack newsletter, Word From the Bird entitled, Men Need Female Heroes! And he’s right. They do. So let’s meet a few’

Perpetua and Felicitas: Martyrs at Carthage (d. 202)

During a persecution of Christians under the emperor Septimius Severus, a group of Christians died together in the arena at Carthage in North Africa. We know precise details of their imprisonment because Vivia Perpetua, a twenty-two year old noble woman, kept a journal–the first known document in Christian history written by a woman. The story of their Passion, concludes with an eye-witness account by an anonymous narrator (who some believe to be Tertullian).

Vivia Perpetua was a well-educated catechumen (i.e. a convert to Christianity who was not yet baptized), from a prosperous family, with a nursing baby. Perpetua, Felicitas, a slave woman in advanced pregnancy, and three men, Revocatus (also a slave), Saturninus, and Secundulus were arrested and placed in a dungeon together. During this time, Perpetua had a dream that she interpreted to mean that their martyrdom was certain. Afterward, her non-believing father came to try to convince her to deny Christ and thus save her own life and that of her baby.

In her own words:

“’there was a report that we were to have a hearing in court. And my father came to me from the city, worn out with anxiety. He came up to me, that he might cast me down, saying: ‘Have pity, my daughter, on my grey hairs. Have pity on your father’do not deliver me up to the scorn of men. Have regard to your brothers, have regard to your mother and your aunt, have regard to your son, who will not be able to live after you. Lay aside your courage, and do not bring us all to destruction; for none of us will speak in freedom if you should suffer anything.’’And I grieved over the grey hairs of my father, that he alone of all my kindred would have no joy in my death. And I comforted him, saying, ‘On that scaffold, whatever God wills shall happen. For know that we are not placed in our own power but in that of God.’ And he departed from me in sorrow.”

Perpetua had another vision, in which she saw herself fighting against a gladiator in the arena, and winning. She understood this to signify victory over the devil.

The narrator writes:

“Now Felicitas was eight months pregnant, and the law did not allow a pregnant woman to be executed. She was accordingly fearful that her death would be postponed, and instead of dying with her fellow Christians she would be put to death later in the company of some group of criminals. She and her companions accordingly prayed, and Felicity went into labor, with the pains normal to an eight-month delivery. And a servant of the jailers said to her, “If you cry out like that now, what will you do when you are thrown to the beasts, which you despised when you refused to sacrifice?” And she replied: “Now it is I that suffer what I suffer; but then Another will be in me, who will suffer for me, because I also am about to suffer for Him.” Thus she brought forth a little girl, whom a certain sister brought up as her own.

When the day of their martyrdom arrived, the guards tried to dress them in the robes of those dedicated to the gods Saturn and Ceres. But Perpetua said, “We are here precisely for refusing to honor your gods. By our deaths we earn the right not to wear such garments.” The guards let them wear their own clothing.

The men of their company died first. The women faced a wild and vicious cow which tossed and wounded them. Perpetua saw Felicitas wounded and took her hand to help her up. Then all prisoners still alive went to the center of the arena to die by the sword. They exchanged a farewell kiss of peace, as was the custom among the Christians, and went to their reward.

Their feast day has always been called by both their names, Perpetua and Felicitas, even though one was a privileged noble woman and the other a slave. Perpetua’s journal became such a beloved text among North African Christians that St. Augustine, then bishop of Hippo, felt the need to warn his people not to give it the same reverence that is due to Scripture alone!

Hilda of Whitby: Spiritual Mother of the English Church (614-680)

We chiefly know about Hilda (or “Hild” as she was known in her own time) from the Ecclesiastical History of the English People by St. Bede the Venerable. She was baptized in 627 by St. Paulinus, a missionary sent from Rome, along with other members of the royal household of her great-uncle, King Edwin of Northumbria. She became a nun. When Aidan, bishop of Lindisfarne was establishing mission outposts and abbeys at the behest of another Northumbrian king, he requested that Hilda establish several monasteries in Northumbria.

That request, in and of itself, is an indication of her reputation at the time, a reputation for wisdom and sanctity. Abbeys in the Celtic Christian tradition of the period were often “double houses”, that is monasteries of men and women with separate housing and a joint chapel, headed by a single abbot or abbess. And so in 657, Hilda founded such a “double house” at Whitby and became it’s abbess for the remainder of her lengthy and influential career.

She herself was a notable teacher. Her advice was sought by kings and churchmen alike while her monastery became a famed center of learning, one of the best in the then known world. She wanted her nuns and monks to grow in wisdom and understanding and so she emphasized Biblical study especially, but education in the arts and sciences as well. Her monastery soon attracted students and became known for both its spirituality and learning. Whitby Abbey produced many leaders for the Church, among them five bishops– Aetla, bishop of Dorchester; Bosa, bishop of York; John of Beverley, bishop of Hexham and York; Oftfor, bishop of Hwicce; and Wilfrid II who became bishop of York after John of Beverley. John of Beverly baptized Bede, who went on to write so affectionately of Hilda.

The normal duties of an abbess during this period included administration, discipline, and caring for the spiritual welfare of her community. An abbess ruled not only her community of nuns (and monks, in the case of double houses), but often exercised authority in both civil and religious matters in neighboring towns and villages and the countryside surrounding her community. Hilda is typically depicted in art holding a crozier, a sign of her authority and responsibility as abbess.

In 664, the Synod of Whitby convened at Hilda’s monastery to consider matters dividing the Celtic and Roman Christians of the time. Patricia Ranft has written of this event, “The fact that the synod, attended by all the leading churchmen of the [British] isles, was held at a monastery ruled by a woman is a tribute to Hilda’s importance among her contemporaries.”[4]

Hildegard of Bingen: Abbess and Polymath (1097-1179)

Hildegard of Bingen has been called one of the most important figures in the history of the Middle Ages and the greatest woman of her time. I think these are not exaggerations.

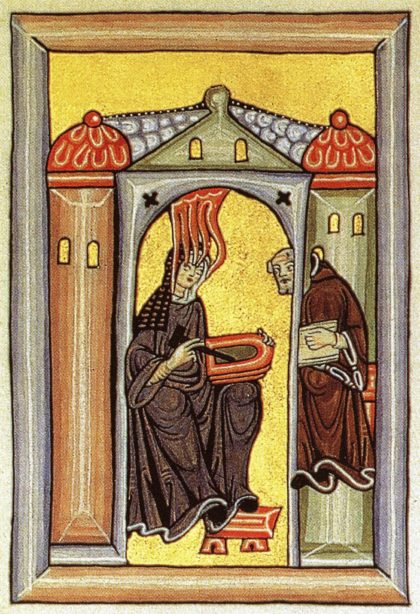

She was educated in a double house and became a nun at eighteen. In her early forties, after being made head of the women’s community of her house, she began to have a series of visions. She spent ten years writing them down, illustrating them, and interpreting their theological significance. The pope got wind of her work, enquired into it and found it to be both orthodox and beneficial. He encouraged her to keep going. She wrote back and challenged him to work harder for the reform of the Church!

Thus began a long career of “speaking truth to power” as she addressed prominent churchmen and statesmen, calling out wrong and demanding that they do better (more than 100 of her letters to such leaders survive.) At the age of 60, she began traveling extensively in her part of Europe, preaching to male clerical gatherings, calling out the corruption of the Church and demanding reform. She said she did so because God had called her to; this despite the fact that she was, in her words, a “poor weak woman”!

In addition to her theological and church work, she composed seventy-two songs and one play set to music–at a time when musical notation had just been invented. This musical play is thought to be the first morality play. She had a deep respect for nature as God’s creation, brimming with His vitality and bearing witness to His glory, something she called Viriditas or “greenness”.

She left about seventy poems and nine books. In addition to her theological treatises, one of her books is a compilation of all the best known medical advice of the period and another is an extensive herbal pharmacopoeia for the treatment of ailments. She invented an alphabet and a language for her own use. Despite these and many other accomplishments, she never thought highly of herself and her advice to others was that, “Those who desire to do the work of God, should never forget that they are fragile vessels.”

There are hundreds more stories I could tell, but time and space limit the number I can tell here. I encourage you to go and find out more. Women have helped to build the Church from the very beginning and still are doing so today!

_______________

[1] Consider this famous quotation of Thomas Aquinas on the ontological inferiority of women, drawn straight from the Greeks: “As regards the individual nature, woman is defective and misbegotten, for the active force in the male seed tends to the production of a perfect likeness in the masculine sex; while the production of woman comes from defect in the active force or from some material indisposition, or even from some external influence; such as that of a south wind, which is moist, as the Philosopher observes’” (De Gener. Animal. iv, 2.)

[2] Martin Luther comments: “’woman seems to be a creature somewhat different from man, in that she has dissimilar members, a varied form and a mind weaker than man. Although Eve was a most excellent and beautiful creature, like unto Adam in reference to the image of God, that is with respect to righteousness, wisdom and salvation, yet she was a woman’though she was a most beautiful work of God, yet she did not equal the glory of the male creature’The male is as the sun in the heaven, the female as the moon, while the other animals are the stars, over which the sun and the moon have influence and rule. The principal thing to be remarked therefore in the text before us, that it is thus written to show that the female sex is not excluded from all the glory of the human nature, although inferior to the male sex.” (Commentary on Genesis, Ch. 1, 1545.)

[3] For a better reading of this and other “problematic” texts, I recommend Lucy Peppiatt’s Rediscovering Scripture’s Vision for Women: Fresh Perspectives on Disputed Texts, 2019, IVP Academic.

[4] Patricia Ranft, Women and Spiritual Equality in Christian Tradition, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 118.

Robin Capcara has worked in university and church-based ministry for forty years. She currently serves with InterVarsity Faculty Ministry in Pittsburgh, ministering to professors at Carnegie Mellon, Pitt, and Duquesne universities and as a spiritual director in private practice. She holds a M.A. in Higher Education from Geneva College and studied at Trinity School for Ministry (Anglican.)

Leave a Reply