In science, change is expected, embraced, and created in the context of community. What if Christians approached faith deconstruction this way?

Faith deconstruction is a process of questioning – of pulling apart the teachings, stories, and cultures that make up our faith, and trying to discern what’s true.

This process is as varied as the humans who go through it. For some, deconstruction turns into demolition: after questioning and examining their faith, some Christians walk away entirely. But for other Christians, the process of faith deconstruction brings them to a richer understanding of their faith and a deeper relationship with God.[1]

One thing is certain: faith deconstruction is happening. Christians have always questioned their faith, but the public visibility of #deconstruction is growing.

As we walk alongside questioning Christians or work through deconstruction ourselves, I wonder if borrowing an analogy of scientific change might help us navigate faith deconstruction a bit better.

——–

I love the history of atomic theory because the changing nature of science is essentially written into the name “atom”. The word (originally the Greek “atomos”) literally translates as “indivisible”,[2] and yet, as scientists like Lise Meitner and her colleagues later proved, the atom can definitely be divided![3]

In the misnomer “atom”, there is a wonderful and messy story of scientific learning and change.

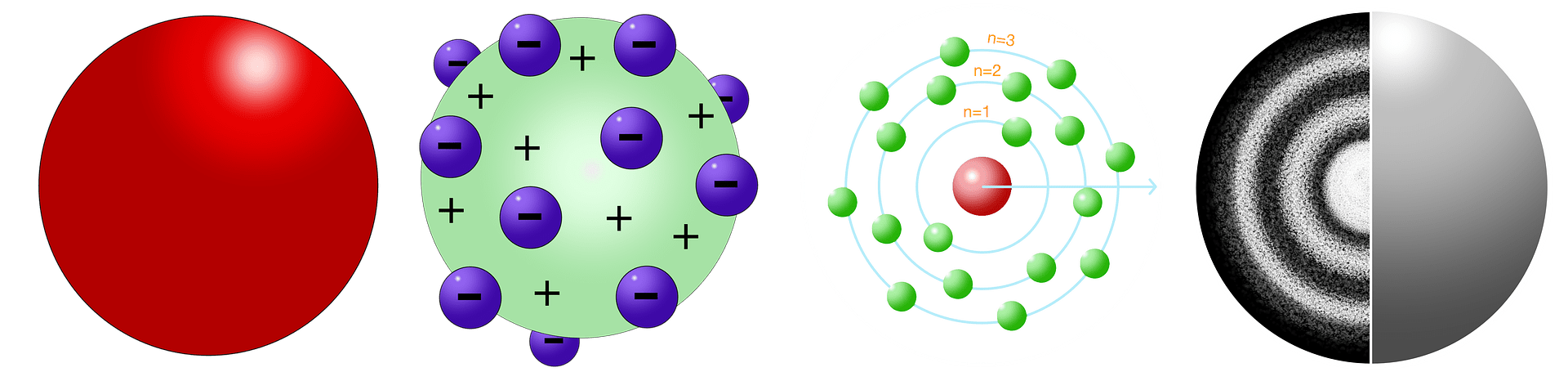

From an indivisible particle to J.J. Thomson’s plum pudding model; from Niels Bohr and Ernest Rutherford’s orbiting electrons to surprising quantum clouds of probabilities [2]; from a jumble of protons and neutrons to Maria Goeppert-Mayer’s onion-like nuclear structure[4] – the atomic model has changed a lot. And (I expect), we’re not at the end of that story.

But through this process of change, the core framework of science remains the same. The scientific method – the process of testing hypotheses with well-designed experiments – is a constant foundation upon which all the changing atomic models are built.

——–

Change (combined with constancy) is a part of the Christian faith too. Reformation is literally written into the name of my own denomination (Christian Reformed).

Sometimes, change in Christianity is driven by new scientific knowledge. Discoveries about God’s world cause us to re-think our interpretations of God’s word with new contexts.

Other times, change comes from listening to Jesus and reading the Bible with new eyes, making new connections, and understanding its meaning in new ways.

I don’t think it’s surprising that our interpretations of the Bible change. Even the disciples (who were with Jesus in person!) couldn’t always figure out when Jesus was speaking literally vs. metaphorically, sometimes with funny results. In John 4, Jesus mentions to his disciples, “I have food to eat that you know nothing about”. The disciples start wracking their brains trying to figure out where he got food’ until Jesus explains that this is a metaphor. If even the disciples struggled to discern when Jesus was speaking literally and when he wasn’t, then shouldn’t I hold my Biblical interpretations with humility and the awareness that I could be wrong?

“Thanks be to God for his indescribable gift!”, Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 9:15. On an episode of The Danielle Strickland Podcast, Darrell Johnson interprets this verse as thanking God for a gift that is “not yet fully unwrapped”.[5] What a beautiful metaphor for how our reading of scripture will change as we discover more of Jesus! We are constantly unwrapping an indescribable gift.

However, change in our faith isn’t always as positive as the experience of unwrapping a gift. Too often, change is necessary because we sin – both as individuals and collectively as the church.

We need change because the systems we build harm the people God loves. We misuse scripture to silence women. We protect reputations and ministries instead of protecting the abused. We build kingdoms of our own power and influence instead of the mustard seed Kingdom of God. We perpetrate and ignore racism. We manipulate faith for political gain. Too many Christians who are deconstructing their faith do so because they have experienced hurt and abuse at the hands of Christians and the church.

The New Testament tells story after story of people who have endured spiritual trauma – the woman at the well and many of the people who Jesus healed come to mind. The religious leaders of Jesus’ day had painted a distorted picture of God’s character that excluded the unclean and marginalized. So, in his ministry, Jesus led a change that embraced the marginalized – including (perhaps especially?) those who were hurt by religion.

This kind of change is still needed today.

—–

But change is difficult everywhere. Even in science, where change is supposed to be the outcome of the scientific method, change is hard. Scientists who propose new models to replace old ones often face long and daunting battles.

On my bookshelf, I have an Ontario High School Physics textbook printed in 1944 that teaches the necessity of “ether” for the propagation of light waves in space.[6] But the Michelson-Morley experiment, performed in 1887 and further explained by Einstein in 1905, demonstrated that the ether does not exist![7] We’re not very good at change.

My husband, Jeremy, recently published a social psychology paper that looked at the impact of changes in public health guidelines during the pandemic. He and his colleagues found that our reaction to changing science around COVID-19 is initially negative: people viewed scientists and public health authorities less favourably when told that public health guidelines have changed. However, he also found that a brief forewarning intervention – simply telling people to expect scientific guidelines to change and framing that change positively – erased this negative response to change.[8] When people expected science to change, they were more able to embrace change.

What might it mean for Christians to approach faith deconstruction this way?

In some Christian communities, there is an undercurrent of belief that change is bad. If a Christian re-reads a Biblical passage and interprets it in a new way, they risk being accused of “watering down the Bible” or “devaluing scripture”. And to change the systems we’ve built that marginalize and harm people is terrifying because it involves looking in the mirror and seeing the cause of someone’s trauma.

But if we expect our faith to change – in the same way that we expect and celebrate scientific change – then we may be more ready to embrace the change that is needed. If we give ourselves a “forewarning intervention” of sorts, we might be able to face change without abandoning our faith all together.

—–

At first glance, the idea of expecting and embracing change in our faith might sound terrifying and probably wrong.

God hasn’t changed. So why should we expect our understanding of God to change? Why should our interpretations of scripture change if the words remain the same?

Underlying these questions, I hear a legitimate fear from Christians: Will people who are deconstructing their faith abandon rich centuries-old theology in favour of an unmoored pick-and-choose faith – or no faith at all?

I don’t have an answer to this fear, but I can share my hope: Jeremiah 29:13-14a says “ ‘You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart. I will be found by you,’ declares the Lord”. King David often voiced lament and asked really hard questions of God in his Psalms. But through his questioning, David sought God – and he found Him.

I realize that the idea of seeking Jesus sounds ridiculous to someone who doesn’t believe. Why would you seek someone who you don’t believe exists?

But I can’t deny the truth of it in my own faith journey. When I have sought God openly and with all my heart, I have always found Him – and I’ve always been found by Him.

I don’t know how to interpret plenty of passages of scripture. I really don’t know how to right the grave wrongs done by the church. But I am convinced that when we seek Jesus, we will find Him. And so I have hope that this indescribable gift – finding and being found by God – is available to anyone who seeks Him.

——

Our analogy to scientific change might also be helpful here.

Scientific change is rarely driven by scientists working alone. There’s a 2015 paper measuring the mass of the Higgs boson that has more than 5,000 coauthors! The paper describing their findings is only 9 pages long, but it takes another 15 pages simply to list the names of the scientists who wrote it.[9]

The large global community of science helps to hold it accountable. Peer review has its issues, but – at least when it’s functioning well – the scientific community can ensure that change is driven by rigorous process.

Can we do faith deconstruction together as a community of believers?

I believe that God made us for community. We need faith communities throughout our lives, but especially through the destabilizing and difficult times of questioning our faith. And yet, there is a tendency for Christians to step away from faith communities when deconstructing their faith.

Unfortunately, it’s not surprising that Christians who are deconstructing often do so outside the church. For some, the church was the place where they experienced trauma. Others face poor hospitality – or even hostility – when they share their struggles and questions within their faith communities. Sitting with questions that have no answers is hard, and faith communities sometimes respond by rejecting those questions – and the questioner.

But what if faith deconstruction was more like the Luke 24 story of two disciples walking along the road to Emmaus? These two disciples were burdened with so many hard questions about the events that had just occurred: Jesus’ horrible death and the mind-boggling reports of His resurrection. As they walk and discuss together, Jesus joins them. He opens the scriptures to them, stays with them, and eats with them. It takes quite a while, but after He breaks bread, finally, they recognize Him.

I imagine that those two disciples were not so unlike Christians who are deconstructing faith today. And I see two beautiful elements in their journey:

First, the two disciples chose to walk together and support each other in their questions.

Second, it wasn’t the disciples’ intellectual analysis that finally brought them understanding and insight. It was Jesus reaching out to them and walking with them.

This is where our analogy to scientific change falls short. In science, knowing comes from studying, testing, and analysing. But in faith, knowing is relational. It is knowing a person – Jesus. So, the disciples on the road to Emmaus achieve understanding through Jesus breaking bread with them.

And that is my hope for Christians – that we can walk together like the disciples on the road to Emmaus, humbly listening to each other and recognizing Jesus.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Peter Schuurman and Bob Trube for your thoughtful feedback on this piece and your insightful questions – you challenged me to think about faith deconstruction from different perspectives, and you made this piece better. Thank you to Syd Heilema who helped to unwrap the road to Emmaus story for me several years ago by telling it as a dramatic monologue.

And thank you to the friends and students who have been vulnerable enough to share parts of your deconstruction journeys with me. As you question, I pray that you are able to walk in community and meet Jesus like the disciples on the road to Emmaus.

_______________

[1] Schuurman, Peter. “Deconstructing Faith, Growing up in Christ.” Faith Today, October 2, 2021. https://www.faithtoday.ca/DeconstructingFaith.

[2] Helmenstine, Anne Marie. “A Brief History of Atomic Theory.” ThoughtCo, November 19, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-atomic-theory-4129185.

[3] Bradford, Alina. “Lise Meitner: Life, Findings and Legacy.” Live Science, March 28, 2018. https://www.livescience.com/62162-lise-meitner-biography.html.

[4] Barral, Miguel. “The Woman Who Reached the Heart of the Atom.” OpenMind, February 19, 2020. https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/science/leading-figures/the-woman-who-reached-the-heart-of-the-atom/.

[5] Strickland, Danielle, and Darrell Johnson. Servant Love w/ Darrell Johnson. The Danielle Strickland Podcast, March 25, 2021. https://www.iheart.com/podcast/256-djstrickland-podcast-31083565/episode/servant-love-w-darrell-johnson-80167360/.

[6] Merchant, F. W., and C. A. Chant. Elements of Physics for Canadian Schools. Toronto, Ontario: The Copp Clark Press, 1944.

[7] Richmond, Michael. “The Surprising Results of the Michelson-Morley Experiment.” http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys150/lectures/mm_results/mm_results.html.

[8] Gretton, Jeremy D., Ethan A. Meyers, Alexander C. Walker, Jonathan A. Fugelsand, and Derek J. Koehler. “A brief forewarning intervention overcomes negative effects of salient changes in COVID-19 guidance.” Judgment & Decision Making 16, no. 6 (2021).

[9] Aad, Georges et al. “Combined Measurement of the Higgs Boson Mass in pp Collisions at √s = 7 and 8 TeV with the ATLAS and CMS Experiments.” Physical Review Letters 114, no. 19 (2015): 191803.

Anneke Gretton serves alongside a fantastic team at Toronto District Christian High School as Vice Principal of Learning. After completing her M.Sc. in Physics Education Research, Anneke taught math and science in Christian high schools for eight years before diving into school leadership this summer. She is so thankful for her two awesome kids, aged one and three, her highly supportive husband, and her extended family who regularly jump in to help and encourage.

Leave a Reply