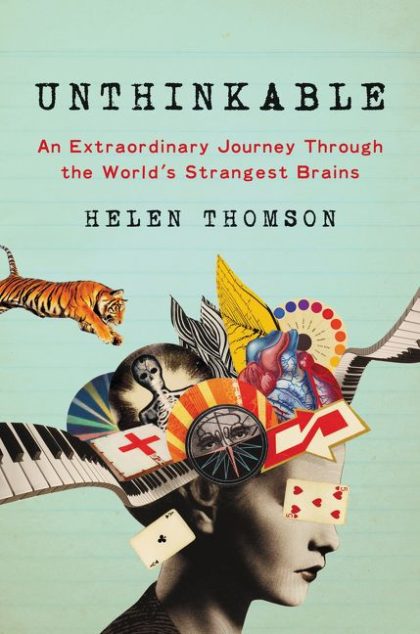

Helen Thomson closes Unthinkable by describing it as “romantic science,” an approach that emphasizes human connection alongside data and clinical reports. The humans in question are not the practitioners of science but the subjects of its investigations. Thomson profiles nine people from all over the world whose subjective experiences of that world push the limits of our ability to communicate about them. She feels compelled to employ rich, high bandwidth personal accounts because an abstraction like “lycanthropy” needs to be grounded somewhere to be comprehensible.

I didn’t know that lycanthropy could be a clinical diagnosis, but a few people genuinely feel they are or can become animals such as wolves, or a tiger in the case of Matar who is profiled in the book. Sure, they can see their external lack of fur or fangs; nevertheless, their internal senses seem to be reporting something different about their bodies than what is visible. Other diagnoses discussed are even more rare. Sharon’s experience of suddenly feeling disoriented, as if everything has shifted around her in an instant, is so uncommon it didn’t have a name–developmental topographical disorientation disorder–until she came forward. Bob’s remarkable autobiographical memory has been clinically documented in 6 people, although other people are believed to have it as well.

As a result of this rarity, we are also at the boundaries of science, a pursuit which relies on repeatability to make progress in reducing uncertainty. Anyone with at least a semester of statistics can tell you a study population of 6 has limited power, but what else can you do when there are only 6 people anywhere with the same experience?

Although Thomson’s emphasis is on introducing us to these remarkable people, their lives, and the positive and negative consequences of their distinctive ways of experiencing the world, she is also interested in how these experiences arise. She supplements her profiles with research on related conditions as well as whatever literature is available for these folks. None of the answers are definitive, but many of the possibilities are intriguing. For example, Sharon’s experience may have something to do with communication between different regions of her brain responsible for integrating and assessing navigational information. Under this hypothesis, a communication breakdown causes errors to accumulate in her mental picture of her surroundings; at some point her mind decides the differences between what her senses are reporting and that mental map are too great and completely reorients the mental version in an attempt to resolve the issues.

As we discussed when looking at Ian Hutchinson’s book Can a Scientist Believe in Miracles?, miracles pose a similar challenge to scientific inquiry. Consequently, both rely heavily on personal accounts. All of the individuals in Unthinkable are notable for their inner experiences. We have a limited ability to quantify or interrogate the minds’ of others; Bob’s memory can be tested in some cases against historical documentation or his previous accounts, but can we ever really be sure Matar is not just claiming to be tiger? Based on how dramatically his life is affected, I can’t imagine why he or anyone would choose to invent such an experience. Still, when profound differences in reported experiences come up, such questions often lurk nearby. Thomson acknowledges such questions fairly early on, shares some of her own initial skepticism about some of her subjects. Ultimately she finds them convincing and wrote these detailed profiles in part to provide enough depth to convince us as well.

Finally, one small detail from the book which struck me came from a discussion of related phenomena in the wider literature. Thomson mentioned a study on body congruence in transgender persons. The findings (on an admittedly small sample) suggest that the brains of transgender individuals process sensory input from gendered parts of their body differently, in a way that makes it seem less like part of themselves. I was unfamiliar with such research, but given the widespread discussion of transgender biology and the policy decisions being made regarding transgender individuals, it seemed important to highlight this work. And I think that’s in line with the overall tone of the book, which encourages both a greater understanding of how our brains and minds work and a greater empathy for people who have substantially different ways of experiencing the world we share.

Next week ESN is hosting a webinar with mathematician Francis Su about his new book Mathematics for Human Flourishing. If this is anything like his last webinar (and why wouldn’t it be?), this will be worth your time. RSVP to Bob Trube (bob.trube at intervarsity.org) to get the link and a discount code for the book.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply