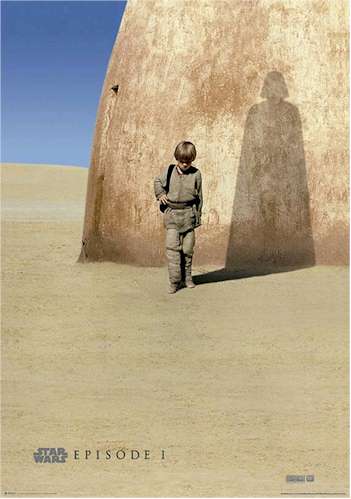

Welcome to the first Emerging Scholars Network Sci-Fi Film Festival! I’ll be having a conversation here on the blog on various classic and current science fiction movies. Feel free to watch along and join the conversation. This week’s film is 1999’s Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace. I’m joined by Mike Beidler. Mike is a retired U.S. Navy commander who is active with the American Scientific Affiliation (ASA) and BioLogos and who has connections to Star Wars stories that I’ll let him explain.

Andy Walsh: This December, the Skywalker Saga portion of the Star Wars story reaches its conclusion… again. Twenty years ago, that saga “began” with The Phantom Menace (TPM) as we all learned the word ‘prequel.’ Seems like a good excuse to revisit what has become a divisive moment in Star Wars and sci-fi fandom. For me, Star Wars was part of my childhood but not central. Return of the Jedi had come and gone by the time I was watching movies and there was no new Star Wars material on the horizon. The expanded universe novels drew me in further as the first Star Wars stories I experienced fresh, and then the Special Edition theatrical releases primed me to be enthusiastic for a new cinematic story in TPM. And so I was.

After I chose this film to chat about, I learned you have a more unique history with Star Wars. Can you share a little bit of your background and your initial reaction to the film?

Mike Beidler: I call those years between Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983) and the near-simultaneous release in 1991 of Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire novel and Tom Veitch’s Dark Empire comic mini-series the “dark times” of Star Wars fandom. Sure, you had the less-than-stellar Ewok television movies and their Saturday morning cartoon followup alongside the better-than-average but short-lived Droids animated series in the mid-80s, but that just wasn’t the same. In 1986, when Marvel Comics ceased publication of its decade-long run of Star Wars, I had a feeling something was wrong with the franchise’s “motivator.” As much of a fan that I was, I had actually stopped thinking much about Star Wars through high school and most of college. That is, until the Zahn-Veitch one-two punch. Seeing that book on the shelf and that comic on the rack, I knew good things were just around the corner!

Little did I know that, with the advent of the Internet and affordability of home computing, my own life would be altered by the Force in ways I couldn’t possibly imagine. In late 1994 or early 1995, after having received my Wings of Gold, I fired off a fan email to comic book writer Tom Veitch. To my surprise, he emailed me back, and we struck up a conversation that, over the course of time, resulted in Tom inviting me to work with him on the Dark Empire saga’s two-issue conclusion Empire’s End (1995). That job led to other Star Wars work, including working with the late A. C. Crispin on the final installment of her popular Han Solo trilogy, Rebel Dawn (1998), which features a Hutt-employed forensic specialist named (wait for it…) Myk Bidlor. Although my involvement in the Star Wars franchise waned as my Naval Aviation career and family life took a front seat, I’ve had the honor of returning occasionally to provide my services to various authors and publishers over the decades. As a member of the extended Lucasfilm family, I even had the (still-surreal) opportunity to visit Skywalker Ranch and rummage through the legendary Archives.

My involvement with the Star Wars franchise probably made me hungrier than your average diehard fan for its return to the big screen, and I actually took the day off of work on TPM‘s opening day to ensure I was the first in line! At the time, I ranked Episode I: The Phantom Menace #3, following Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Episode IV: A New Hope (1977). Looking back, I think that I ranked TPM that high for two primary reasons: (1) it was brand-new (not merely “tweaked”) Star Wars on the big screen again and (2) it took advantage of the recent leaps in CGI technology to great effect (pun not intended). However, over the last two decades, my overall assessment of the film has declined considerably; sadly, I now rank it the “worst” of the entire saga. Every year or so, I give the entire saga a run-through, and such an exercise only reinforces my belief that TPM simply hasn’t aged well.

AW: What elements, if any, still stand out to you as worthwhile?

MB: There are aspects of the movie that I love, such as the pod race, Anakin’s rise from slave to padawan learner, Palpatine’s delicious political machinations, and the discovery of what Jedi could really do beyond lifting seaweed-covered starfighters out of swamps, crush windpipes, and redirect blaster fire. Of course, there’s that one sequence worth the price of admission: the lightsaber battle between the underused Darth Maul and the tag-teamed Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi. Everything else paled in comparison. The acting abilities of Liam Neeson, Ewan MacGregor (Dennis “Wedge” Lawson’s real-life nephew), and Ian McDiarmid carried the movie far beyond George Lucas’ inferior and bloated script, leaving me somewhat discouraged with Natalie Portman’s wooden performance as Queen Amidala and the too-young casting of Jake Lloyd as young Anakin Skywalker. These days, I also find A New Hope‘s groundbreaking miniatures work and matte paintings superior to TPM‘s sorely-dated CGI. Clearly, we’re spoiled by how good CGI has become. I watched a video that gives a peek into the extent to which J. J. Abrams used CGI on Episode VII: The Force Awakens (2015), and I was astounded; I initially believed much of it to be old-school miniature work. Do you also find the CGI dated?

AW: Absolutely. I feel similarly about the Special Edition CGI additions; they look more dated now than the matte paintings and models they share the screen with. At the same time, I think it’s only right to mention that the comparison isn’t exactly fair. The work on the original films, while innovative, built on techniques that had been refined for decades. By contrast, the CGI of TPM was the product of early-generation technology. George Lucas may have jumped the gun on declaring the tools and resulting visuals ready for primetime, but I can’t fault him for correctly recognizing their potential and wanting to help advance the field. In that regard, and also with respect to elements like the dialogue and underdirected performances, I find it helpful to think of the prequels as the most expensive and populist experimental art films of all time. And as a result of those experiments, we now have photorealistic films that we call live action but, as you noted, when you go behind the scenes, they are closer to animation than we realize. A “more machine now than man” joke is tempting here.

Do you think TPM could have benefited from waiting a decade or so for the technology to mature? Or was it a necessary step in that maturation process?

MB: You make a good point about my somewhat unfair comparison of TPM‘s dated CGI. I appreciate your recommendation to think of the prequels as “the most expensive and populist experimental art films”! I’ve not heard that particular description before and, at first blush, it blunts my criticism’s sharpness a bit. While I think TPM as a movie experience would certainly have benefited from a decade’s worth of CGI technology maturation, I believe a decade-long delay in bringing Star Wars back into the forefront of the public’s movie-going consciousness would have been disastrous for the franchise. Thus, I don’t fault George for jumping into the fray when he did, as I don’t believe novels and comics alone would have carried the franchise beyond Star Wars‘ 50th anniversary, which it is now well-positioned to do. The one thing I’ve admired about George Lucas is his willingness to take chances and take an early lead in terms of movie-making techniques and digital film distribution/projection. I’m of the opinion that, with TPM, George singlehandedly led a cinematic revolution that “democratized” movie production, making it easier and more affordable, leading directly to an uptick in movie-making creativity. Nevertheless, I think that George’s same pioneering spirit also led to some of his more unforgivable movie-making excesses and missteps mentioned earlier. Allow me to adapt one of Dr. Ian Malcolm’s lines from the original Jurassic Park: “George Lucas was so preoccupied with whether or not he could, he didn’t stop to think if he should!”

AW: He has certainly seemed willing to allow the fan community to make films inspired by his galaxy far, far away when others might have lawyered up. And he did pioneer shooting movies digitally with these prequels; as I recall he intended to do so with TPM, but the pipeline wasn’t quite there until Episode II. Now we have the likes of Steven Soderbergh shooting feature-length films on a phone, and Gareth Edwards making Monsters using consumer cameras, laptops, and visual effects software (and then being hired to direct Rogue One: A Star Wars Story). While Lucas wasn’t the one pushing all of the hardware innovation, I think it’s fair to say he was a pioneer in using that tech for cinema.

)

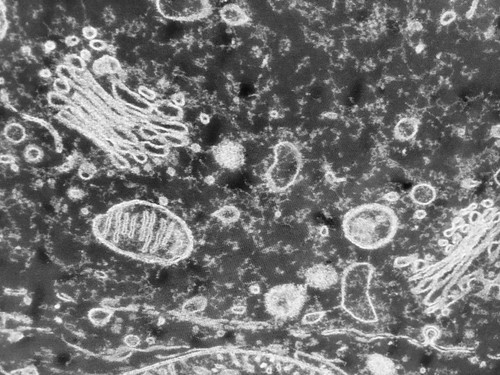

)Do you have any views on the film that go against the consensus? I have gone on the record as actually liking the idea of midichlorians, because they bring some cell biology to a world of lasers and hyperspace.

MB: I’m not sure if I have any anti-consensus views about the movie, although perhaps Shmi Skywalker’s virginal conception of The Chosen One may qualify. I actually appreciated George Lucas’ interweaving of mythical beats (the good, Tolkienesque kind, of course) into his stories about the star wars. I loved the idea of the Force willing a savior into existence. What did you think about Anakin being born of a virgin? Too close to Jesus for comfort?

AW: I don’t have strong feelings about that particular story point, I think in part because the film itself doesn’t seem to have strong feelings about it. I agree that it adds a mythic quality. You can see where Lucas is playing with our expectations. He is layering Anakin’s backstory with the trappings of heroic origins and being the Chosen One. Subverting those expectations by having Anakin turn to the Dark Side and become Darth Vader could have been a very effective twist, but of course everyone knew that was coming. The end result is still somewhat operatic, but not actually engaging.

The similarities to Jesus are not troubling to me. I don’t think it takes anything away from the story of Jesus. On the other hand, it does add a curious wrinkle to Anakin’s tale. Why was it so important to the Force that Anakin be born? Did the Force know everything that would result? Did the Force will or intend those outcomes? Are we meant to think of the Force as benevolent given the lengths it went to murder all those younglings?

And while we making Jesus comparisons, I think it’s worth noting that the Gospels have the good sense to look in briefly on pre-teen Jesus before focusing mostly on his adulthood. Even though we still would have known where it was going, I wonder if we would have bought into the journey if Anakin was more of a young adult. Corrupting an earnest adult Anakin who could have possibly chosen differently sounds like a more compelling story than one of a child being unwittingly tricked. No one wanted to learn that Darth Vader was a patsy. The model here I suppose is Michael Corleone’s story in The Godfather. I don’t know how much we were meant to expect Michael to stay out of the family business, but there is still real tragedy to the story even if you know the ending.

MB: I think you’re spot on, and I wish George would have thought more along the lines of The Godfather, which is ironic given his close relationship with director Francis Ford Coppola. I think this is a great example of George having too much control over his own creation. George’s better Star Wars movies, it seems, occur when he’s in a more collaborative mood.

Next week, Mike and I will continue chatting about The Phantom Menace as we explore issues of canon and prophecy. I hope you’ll join us; we’ll save a seat for you!

Mike Beidler is a retired U.S. Navy commander whose combination of military aviation experience and Star Wars fandom pedigree launched him, beginning in the mid-’90s, into a decades-long relationship with numerous Star Wars authors. His direct contributions to the Star Wars universe include work on Tom Veitch’s Dark Empire saga, A. C. Crispin’s Han Solo trilogy, and John Whitman’s Galaxy of Fear series. He has, in a galaxy far, far away, worked as a forensic specialist for a Hutt crimelord, studied with the B’omarr monks of Tatooine, and hunted down a bounty or two. He has also written about Star Wars and Blade Runner for Sequart Organization. In this galaxy, however, he lives in northern Virginia with his wife and three children and takes advantage of his daily 45-minute commute to/from the Pentagon to read theology and science fiction. Mike is President of the Washington DC chapter of the American Scientific Affiliation (ASA), a contributing writer to BioLogos, and a member of the both the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and the National Center for Science Education (NCSE).

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Leave a Reply