Like most who are part of the academe, I consider myself a well-read person, though we all admit that the more of an expert you become in one area, the more you realize how ignorant you are in others. My focus is the 19th Century American religious environment and even when I stray from there to another research focus, I always come back because I find the century so interesting. Sometimes, to get a more complete view of the period, I will read fiction from the era since it gives a window into the period’s views about religion which theologians do not and cannot. In addition, I am just interested in literature and I listen to a lot of books during my commute time. Rarely do I intentionally put one down unfinished, though several have challenged me in that regard. One book which I started but just could not finish was Moby Dick; it was just so long, and seemed so disconnected from the tale of Ahab that I just couldn’t finish it. Consequently, I became very critical of the book; how could a book filled with so much detail about whales and whaling be considered such a great American classic? But in the best way that students can, my own hypocrisy was pointed out: how could I be so critical of book I openly admitted I had not read completely? I hate it when people point out my own inconsistencies. So, this summer I committed to reading the whole of Moby Dick, even though I had previously failed and I already knew how the book ends.

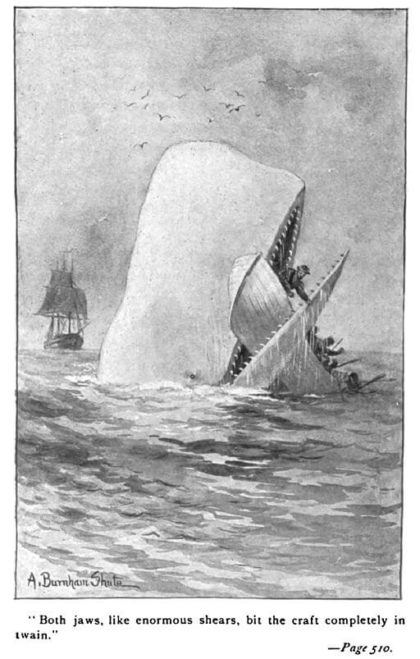

And that’s the rub. Nearly everyone knows the story of Moby Dick, though many have only interacted with it through an abridged version of the book, or through one of the movies made about the story. The story has obtained near universal cultural penetration. Nearly everyone associates the story of Ahab and his search for Moby Dick with any kind of obsession which borders on the self-destructive. Anyone who moves into the category of “I don’t care what it costs me” is bordering on the “white whale” monomania which Herman Melville makes the core of the drama of his story. Ahab’s obsession cost his life and the lives of his crew, save one, who lived to tell the tale.

Moby Dick is a story we know, at least culturally. And yet, most do not actually read the book. I won’t go into a diatribe about how people don’t really read books anymore, because I think in the end it is not really much different than it has always been. Distractions have changed, but basically since the advent of television, we as a society do not read as much as we used to. And much of modern education does not focus on the classics or even on reading whole books. So, no finger waggling; the culture has made us thus and thus we are.

With Moby Dick, however, I think the reason we don’t read the book is because it is intimidating, and frankly, really dull in sections. My edition is 560+ pages, and much of those are disconnected from the story of Ahab, the Pequod, and the hunt for Moby Dick. Most of the book is about whaling, rather than about the whale, even though that was Melville’s original title for the book. In fact, if you get right down to it, the main action of the story, the chase of Moby Dick, really only occupies the final three chapters of the book. The rest of the book is one really long plot development. Those looking for an adventure story, like myself, get bogged down in the details about whales.

And that is the difficulty with the book: it really isn’t a novel or even a story in the way we think of stories today. My edition has a short commentary at the end of the book, written by Howard Mumford Jones, in which he claims that the book is best understood as a journey book, like The Odyssey or Dante’s Divine Comedy. And I think that makes some sense; perhaps it can be likened to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books in that regard. Both are about long journeys, and both books are written by authors who have an excellent command of the English language. Additionally, both create a world, often with excruciating detail, which creates a backdrop on which the story takes place. Of course, not many would have read (and reread) all three volumes of Tolkien’s tome if Frodo had gotten to Mt. Doom, only to die and Sauron gets the ring.

So, if this is truly a journey book, which is as good of genre placement as any, how does that change the way we read Moby Dick? Because here is the problem: Moby Dick is as long as it is because it is filled with details about whales, whaling ships, life aboard whaling ships, whaling in general, whaling traditions, whaling history, the science of whales, the whaling industry in the early 19th century’well, you get the idea. It’s a lot of stuff about whales. My first attempt to read the book stalled at chapter 32, “Cetology,” in which Melville discusses the sizes of whales compared to book sizes (folios, octavos, duodecimos). This means that you also have to know pre-20th century book sizes for that chapter to make much sense and even then you get the end of the chapter and wonder why I had to read this to understand the search for Moby Dick. He discusses the whaling industry in great detail, sometimes mind-numbing detail about the hunt, harvesting, profitability, and uses of whale oil – the erstwhile reason the Pequod was sailing in the first place.

If you can survive through the minutia, what makes Moby Dick such an iconic book, and further, why should anyone bother taking up the massive tome (assuming they haven’t been guilted into it!) and read 500+ pages when anyone knows how the book will end? First, let me say that the book is in fact a masterpiece of English language literature. Melville certainly deserves his place among the great writers for his mastery of the craft of writing. His command of the language is followed closely by his command of detail. Even though this story is not real, at least in the sense that Melville was on a whaling vessel which was hunting for Moby Dick, Melville nevertheless places the story in a world which was very real. And in the end, this richness of detail does help us understand the world as it might have existed if we were to go back in time and join the crew of an early 19th century whaling vessel.

Secondly, he gives us an excellent picture of life in the 19th century. Melville does not simply create a fictional world, as does Tolkien, he creates a world which operates in an existing tradition; actually, many traditions. The Nantucket whale men are Quakers and they act as Quakers of the 19th century might have, were we able to transport ourselves to Nantucket. Many of the crew are men of different non-American and non-European cultures, each with their own traditions. Melville does not treat these men or traditions as inferiors whose cultures are to be bulldozed over by the superiority of the white man’s traditions. Does he speak with the many of the prejudices of the 19th century? Yes, however that is also a tradition which he presents correctly. Moby Dick is many things; political commentary is not one of them. However, you would also have a hard time reading 19th century imperialism into Melville’s treatment of non-white cultures and peoples. Queequeg is a pagan for Melville, but a pagan with honor, dignity, and a tradition worthy of being respected.

Thirdly, and perhaps finally (I would love to spend some time talking about Melville’s use of religion, but perhaps that needs to be its own post), Melville weaves his characters into a story in a masterful way. We are introduced to the monomaniacal Ahab as an apparition; more spirit than man. And monomaniacal he is – the white whale took his leg and now he wants revenge, consequences be damned. But as the book unfolds, and Melville unpacks the character of Ahab, he becomes more man, and less spirit. He even regrets bringing the whole of the crew into his mania. This is especially true of Starbuck, his first mate. When we finally get to the chase, Ahab insists that Starbuck remain on the ship to protect him in order that he might be able to return to his family. But in the end, Ahab’s bloodlust overwhelms him, the ship, and all hands. And this is the part of the book which gets the most airtime, especially in sermons on Romans 12:19 (I will always hear this verse in the sternness of the King James Version which works well in the story of Moby Dick). Perhaps rightfully so. But my worry is that by reducing the story of Ahab’s search of the whale to a morality tale, we miss the greatness which is Melville. Moby Dick is not The Lord of the Rings told through Gollum’s eyes. To make it thus, is to do what I did – miss the greatness of the book by focusing on one part of the book rather than the whole.

Moby Dick is a long book about, ostensibly, the search for a single whale by a single ship in the vast oceans of the world. However, it is more than that: it is the story about humanity and its search for meaning in a world which, by the 19th century, was becoming smaller, and more mechanized, and more disconnected from the world which had given birth not only to humanity, but Western civilization. Into this Enlightenment-driven world, which literally demanded a way to stave-off the dark (thus the search for whale oil) a small boat leaves a small island in search for a single whale. The world which Melville records is not the world tamed by man; it is a world which fights back, and sometimes, through the lens of a white leviathan, even wins. Moby Dick is a romanticized, nearly mythical world, and yet it is a world which did exist for the men who ventured forth to do battle with the great beasts of the globe. Whaling, despite Melville’s predictions, went the way of all things in the 19th century and industrialized. As a result, the whales of the oceans were hunted nearly to extinction in man’s quest for mastery over nature. Had not petroleum been refined to be used as a light source, a new “dark” age might have ensued. But the monomaniacal spirit of man survived, and we limp forward on our peg leg, the symbol of our mania, always searching for meaning in a world in which we are both hunting and hunted. In the end, we are Ahab; this is the genius of Melville.

I am a PhD student in theology at Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. I am studying the theology of John Williamson Nevin, who taught in the seminary of the German Reformed Church in America in the mid-nineteenth century. He was also the president of Franklin and Marshall College and a friend to James Buchanan, the 15th president of the United States. I am currently a teaching fellow at CUA, teaching undergraduate theology and Church History classes. My goal is to teach at a college or university after completing my degree program. I am also the current vice-president of the graduate student association at CUA. Before life as a grad student (if that were an acronym it would be BLaaGS) I was a teacher and principal in secondary education at various Christian schools in the Northeast. My family and I currently live in Hagerstown, MD.

Michael, you worked thru Moby Dick! Well done! You laid out the problems reading very well. It took me about 5 tries to finish it but more to work thru it. Ihave read biographies on Melville as weliIl as read his other works. MB was not recognized as great until about 1920. Melville was ahead of his time. I th-ink you have a good grasp of the bk – it’s just that often it feels like there is so much more to be gleaned. Meville was friends with Hawthorne, but it didnt work out as Meviie hoped. So much there! Thanks Michael.

A genius review, Mr. Stell. That last paragraph deserves a standing ovation. Who would have thought that such a seemingly boring book could have so much to unfold and explore? Melville would be proud in my opinion— you understood him. I’m honored that I was challenged to read it too.