How do we know this is what John Locke looked like? (Photo by deemikay

)

)Let’s try a Google hangout to chat about the book in person. Use this link to indicate your availability.

Welcome (back) to our ongoing discussion of The War on Science. Last week we looked at chapters 1 and 2 which basically introduce Shawn Otto’s thesis about the relationship of science and democracy and its current state. That material already spurred several lines of discussion, including the role of interpretation in understanding observations which will be relevant this week as well. This week’s chapters begin Otto’s highlights of American history and the roots of its democratic and scientific traditions, with a dollop of religious history as well. Let’s take a look and see what he has to say.

In Which Otto Illustrates His Point about the Need for Careful Inference from Observation

Overall, I appreciated the tour through history these chapters took us on. While this brief treatment of substantial trends and threads should not be mistaken for a comprehensive history, the choice of moments to highlight felt broad and balanced. I thought there was a reasonable mix of both well-worn touchpoints—Locke and Newton and the Scopes trial—and less familiar anecdotes—the Muslim scientists who influenced European science and the conservative roots of some American academic institutions including both of my almae matres.

We’re in the territory of facts and observations, which Otto frequently reminds us are reliable markers of the path to truth. At the same time, perhaps because of the tone of the first chapters, I am still a little wary of how he discusses this historical data and the conclusions he draws. For example, chapter three opens with these questions: “Was America always a nation of science? Or was it founded as a Christian nation?” This feels like a false dichotomy, both because those aren’t mutually exclusive options and because they don’t represent the full range of possibilities. As a rhetorical gambit such questions may be a fine way to get the discussion rolling, but in the very next paragraph we get a fairly definitive answer: America was founded on science and not as a Christian nation.

What follows is the data from which Otto draws this conclusion, and to my mind they paint a more complex picture. There is legitimacy in asserting that America was not founded as a Christian nation, especially if the alternative involves weaving modern theology into eighteenth century history. The founders were a diverse bunch theologically, perhaps giving them an appreciation for preserving religious freedom. But that doesn’t mean America was founded on purely areligious scientific principles. Through the details recounted in the book, we see scientific principles and the motivation for applying them to governance both rooted in Biblical theology. Otto makes much of Benjamin Franklin’s suggested edit to the Declaration of Independence which replaced “sacred and undeniable” with “self-evident” but the idea of a Creator God remains in the text as well.

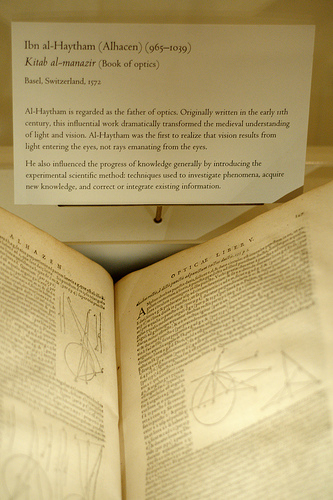

As Otto continues to explore the history, he highlights a number of other religious scientists, including Islamic scholars Muhammad ibn Musa al-KhwÄrizmÄ« and Ibn al-Haytham, Isaac Newton, and Georges Lemaître. He acknowledges their theology which place the book of nature alongside scripture as a source of knowledge about the divine. Clearly he recognizes that scientific investigation and religious belief are not incompatible. Yet every now and then we get a reminder that he considers those scriptures to be just “old books” in contrast to the contemporary immediacy of scientific observation.

)

)Compel Him to Include Epistemology in the Sequel

Otto has this to say about Franklin’s famous edit: “This was a self-evident truth that proceeded from careful observation of nature through our knowledge-building process—the same process that we use in science.” He traces the phrasing to Locke’s concept of intuitive knowledge, but what he actually describes sounds more like Locke’s demonstrative knowledge to me. And so the idea that liberal democratic ideals are a matter of scientific inference, which Otto seems to be suggesting, does not appear to actually be what Franklin and Jefferson had in mind. And even if it were, epistemology has come a long way since Locke. Self-evident axioms are not universally recognized, even within the more formal and precise domain of mathematics. Perhaps going forward we’ll get a contemporary updating of the philosophical foundations of democracy and science.

And as a biologist, I am not quite ready to base a system of government on observations of sheep grazing. For one, I’m not persuaded the sheep are really voting. Yes, there is bottom-up emergent organization to herd dynamics. But is there a sense of a binding agreement? Do the sheep enforce the decision of the group on possible dissenters? For another, and more importantly, is there evidence that majority-rules decision making leads to better grazing than an authoritative top-down approach would? Just because a solution exists in nature doesn’t mean it is the best one.

Voting and democracy are abstractions. Even if they can be derived from biological data, that level of abstraction requires interpretation. They do not simply follow from a ‘plain reading’ of the facts. And this is a key concept that hasn’t really been addressed in the book yet. There are a few references to human fallibility and the possibility of reaching wrong conclusions, but the general sense is that if we following the scientific method, we’ll collectively arrive at objective truth. And yet just in these chapters we have conclusions that don’t seem to follow from the data offered in support of them.

The Authoritarian Axis

Perhaps some of the confusion comes from projecting everything onto the axis of authority. In many ways, authoritarianism is a helpful lens. It shifts emphasis away from the conservative/liberal axis along which many stake their political identity, allowing Otto to highlight examples of both conservative and liberal support for science. At the same time, he clearly wants to establish both science and democracy as anti-authoritarian, which requires downplaying the role authority plays in each, particularly the specific republican democracy the founders instituted. Meanwhile, despite discussing anti-authoritarian strains of theology, religion winds up being cast in more of an authoritarian role, appealing to the authority of “old books.” Having been plotted on opposite sides of this spectrum, religion and science appear in tension even though ample examples to the contrary are presented. In light of this authority lens, I’m curious how Otto will handle anti-authoritarian rejection of science rooted in suspicion of experts and elites.

Discussion Questions

- Such a brief historical survey is bound to have omissions. Are there any events or people whose inclusion might significantly shift the conclusions?

- The United States was described as a land of pragmatic tinkerers and engineers, in contrast to the European tradition of learning for its own sake. Do you think that was true in the era to which it was applied? Do you think that is still true?

- How do you describe the foundational principles of the United States?

- In describing the United States as the oldest democracy, is the significance of classical influences on the founders being minimized?

Feel free to ask and answer your own questions as well.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

Thank you again, Andy.

The historical information is indeed valuable and appreciated.

Your question about omissions in this brief history brings B.B. Warfield of Princeton Seminary to mind. Prior to the height of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy and the Scopes Monkey Trial, which Otto holds up as a model of Christian anti-science sentiment, Warfield was open to Darwin’s theory of evolution. (http://biologos.org/blogs/archive/b-b-warfield-biblical-inerrancy-and-evolution/). Yet Otto overlooks this important figure in early twentieth century Evangelicalism.

I am also troubled by the assertion in on page 66 in Chapter 3 that Christian fundamentalism believes that God is the only cause at work in the physical world. He also makes a similar assertion about Muslim fundamentalism, but I lack the background to explore that in any depth.

Thank you again.

That’s a good point about Warfield. What particularly stuck out to me in that link was that one hundred years ago, Warfield was already making a distinction between Charles Darwin the man and Darwinism, and further distinguishing mechanistic study of evolutionary biology from materialist world views. Even now, those categories are conflated.

The work of Ted Davis, who has also written for BioLogos (http://biologos.org/author/ted-davis), is another good resource for the nuances of Christian engagement with evolutionary biology over the years. Another earlier figure he often references is Asa Grey, a Christian botanist contemporary of Darwin, although Grey is perhaps less relevant to Otto’s points about Evangelicalism.

I’m not sure about fundamentalist theology, but in practice it does not seem that theologically conservative Christians believe God is the only cause of anything/everything. Perhaps he is the ultimate cause, but not the only cause to the exclusion of more proximal agents. Plenty of such Christians find science to be a fruitful field of study and are happy to apply and make use of many of its findings. Not to mention that such a theology would eliminate free will and make God responsible for all sin. The assertion feels like an unhelpful oversimplification, if not an outright misunderstanding. This week’s reading (ch 5-6) largely stays away from religion; we may need to return to this issue when we get to chapter 9 to see if Otto adds more nuance when he goes into more detail on religion.

Thanks for the comments.