Mark Hansard shares another exploration of faith in Victorian literature. See previous posts exploring Browning and faith and Gerard Manley Hopkins and how aesthetic experience can point to God.

Robert Browning’s “An Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish, the Arab Physician” is another fine example of dramatic monologue in which the character speaking reveals things about himself he is unaware of, but through the irony of self-disclosure, the reader readily sees. As I explained in my previous post, Browning was a Christian in Victorian England who, in many of his poems, engaged serious intellectual objections to Christianity.

“Karshish the Arab Physician” is a poem that purports to be a letter from Karshish to his mentor in the medical arts, Abib. Karshish wants to report an unusual encounter he’s had with Lazarus, a Jewish man in Palestine who claims to have been raised from the dead by a “Nazarene physician” (line 100). But Karshish does not want to appear credulous to his esteemed colleague, and wants to keep up scientific appearances so he is not dismissed as crazy or naïve. Thus, he endeavors to restrain himself in his descriptions of Lazarus, while sprinkling his epistle with various medical observations and his skepticism regarding Lazarus’ account.[1]

The poem is pregnant with irony as Karshish attempts to present himself as someone who uses the latest in medical technique, which the reader can clearly see is primitive and archaic. While Karshish drops various ludicrous medical observations, he is attempting to prove to his medical mentor that he is a scientist, unaffected and objective about even the strangest stories, like someone rising from the dead. Instead, the reader knows the truth: not only is Karshish not a scientist, he is not successful in hiding his curiosity and enthusiasm for Lazarus’ story.

Karshish begins his letter by describing himself as “the picker-up of learning’s crumbs,” a “vagrant scholar” who sends to “Abib, all sagacious in our art” “three samples of true snakestone—rarer still,/ One of the other sort, the melon shaped . . .” (1, 15, 7, 17-18). The reader is struck here with the irony that a “scholar” would believe snakestone is any kind of a cure worth collecting, as well as Karshish’s lack of a scientific name for one that is “melon-shaped.” This sampling of medical knowledge is just the beginning of Karshish’s ironic self-disclosures. In fact, he declares that he doesn’t know whether the Syrian who is carrying the letter to Abib will steal it and the enclosed (valuable!) cure, as Karshish had “blown up his nose to help the ailing eye” (51). What cure for the Syrian’s eye he had squirted up the man’s nose is anyone’s guess, but the Syrian man was delivering the letter as payment for the treatment.

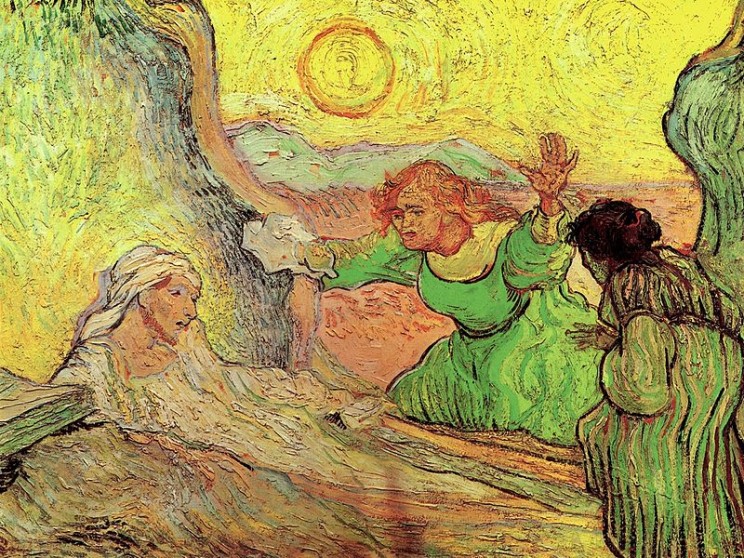

After he has introduced himself and proven his medical prowess, Karshish goes on to delicately introduce the Lazarus story by saying, “’Tis but a case of mania . . . of trance prolonged unduly some three days . . .” that was caused by epilepsy or “some drug” (79-81, 82). He is at pains to seem scientific and not naïve, but after his description of the “mania” he describes Lazarus’ peculiar situation as if “flinging (so to speak) life’s gates too wide,” the “just-returned, newly established soul” had something inscribed upon it, “that nothing subsequent/Attaineth to erase those fancy scrawls” (87, 94, 92-93). In other words, Lazarus appears to have had an unusual experience which caused his soul to be inscribed with unusual knowledge. Karshish says he claims “he was dead (in fact they buried him)/–That he was dead and then restored to life/ By a Nazarene physician” (98-100). Lest Abib think he has gone mad, Karshish hastily adds, “’Such cases are diurnal,’ thou wilt cry . . .” And then goes on to defend his observations of Lazarus.

Apparently, Lazarus was so taken with the eternal, he is no good for this earthly life now, “obedient as a sheep,” he “eyes the world now like a child” (119, 117). “The man is witless of the size, the sum,/The value in proportion of things” because “Heaven opened to [his] soul while yet on earth” (143-44, 141). And Karshish finds this astounding and compelling in spite of himself.

In what is perhaps the most ironic passage in the poem, Karshish identifies with Lazarus’ impatience. While Lazarus is impatient at “carelessness and sin” because of his otherworldly experience, Karshish feels he understands as he is impatient with those who pretend to know what good medicine is: When I “happed to hear the land’s practitioners,/ Steeped in conceit sublimed by ignorance, Prattle fantastically on disease,/Its cause and cure—and I must hold me peace!” (239-42). Here the reader, no doubt chuckling by now, knows that it is Karshish himself who is “steeped in conceit . . . sublimed by ignorance.”

There are many Browning scholars who believe the irony in the poem is a satiric comment on German Higher Criticism, a well-known assault on the historicity of the Scriptures in Browning’s day. On this view, Karshish and Abib represent historians and theologians who, thinking they are using the latest in research techniques, are hopelessly unable to apprehend the truth of traditional Christianity. Knowing Browning’s critique of Higher Criticism in a number of his other poems, this view seems likely. If so, it is a brilliant comment on the intellectual problems of his day.

As Karshish ends the poem, he again gushes over Lazarus’ story in spite of himself. Even though he has just pleaded, “For the time this letter wastes, thy time and mine/ . . . once more thy pardon and farewell!” (302-03), he cannot stop there:

The very God! think, Abib; dost thou think?

So, the All-Great, were the All-Loving too—

So, through the thunder comes a human voice

Saying, “O heart I made, a heart beats here!

Face, my hands fashioned, see it in myself!

Thou hast no power nor mayst conceive of mine,

But love I gave thee, with myself to love,

And thou must love me who have died for thee!”

The madman saith He said so: it is strange. (304-12)

Strange indeed.

Questions for Reflection

- Do you think intellectual pride is a problem in the Academy today? Why or why not?

- Does Academic pride sometimes blind one to the obvious? Can you think of an example in your own career or others in your field where you have seen this?

- Have you sensed your own struggle with pride? What do you do when you are tempted to feel prideful?

For Further Reading

- Browning, Robert. “An Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish the Arab Physician.” In The Works of Robert Browning, with introductions by Sir F.G. Kenyon. Vol IV. Barnes and Noble, 1966, pp. 89-98.

- Crowell, Norton B. “An Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish the Arab Physician” in A Reader’s Guide to Robert Browning. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972. 131-39.

- DeVane, William Clyde. A Browning Handbook. New York: F.S. Crofts and Co., 1935. 199-201.

Notes

[1] For this analysis I am indebted to Norton B. Crowell, A Reader’s Guide to Robert Browning (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972), 131-39.

Mark is on staff with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship in Manhattan, Kansas, where he ministers to Faculty at Kansas State University and surrounding campuses. He has been in campus ministry 25 years, 14 of those years in faculty ministry. He has a Master’s degree in philosophy and theology from Talbot School of Theology, La Mirada, CA, and is passionate about Jesus Christ and the life of the mind. Mark, his wife and three daughters make their home in Manhattan.

Leave a Reply