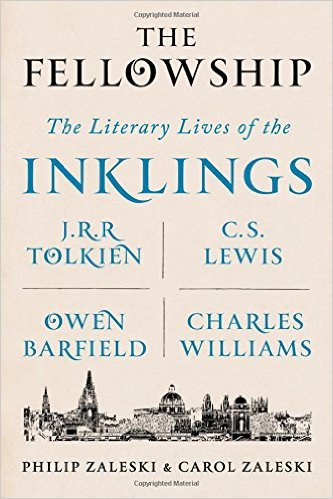

The Fellowship, Philip Zaleski and Carol Zaleski. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2015.

Summary: This traces the literary lives of the four principle Inklings (Lewis, Tolkien, Barfield, and Williams) the literary club they formed and its impact on literature, faith, and culture.

This is a magnificent book for any Inklings lover! It serves at one and the same time as a quadruple biography of the four principle Inklings and traces the formation, life and impact of this literary gathering of scholars (all men) and their wider impact on many others, including women like Dorothy L. Sayers.

As biography, it brings to life these four figures as well as biographies I’ve read on any individual Inkling. Lewis has been written on the most, and yet I thought the Zaleskis teased out more about his relationship with Warnie (who submerged his own career to a certain degree for that of his brother, and who in turn was cared for by Lewis as he struggled with alcoholism), as well as Lewis’s relationship with Mrs. Moore. We see Tolkien as a deeply devout Catholic often concerned over the spiritual lives of his sons, and his lifelong struggle to bring forth the tale of Middle Earth. We learn of Owen Barfield’s obsession with anthroposophy, and the often affectionate, sometimes not relationship with Lewis as his most significant sparring partner (he later, for a time, had an influence on the American writer, Saul Bellow). And last, we learn of the mystical romantic Charles Williams, the Oxford University Press editor who wrote “supernatural shockers” and had “interesting” though chaste relationships with a number of women attracted to his romantic vision, and whose early death in 1945 was deeply grieved by Lewis.

We also learn of the formation and inner life of this all-male discussion group. Serious discussions occurred on Thursday evenings, usually in Lewis’s rooms in Oxford. Often these consisted of the reading and critique of works in progress. It was here that Barfield’s works on language, Lewis’s Space Trilogy and Tolkien’s Hobbit and Fellowship of the Ring first made the light of day. If it weren’t for the encouragement of this group, as well as Tolkien’s publisher, this latter work may never have been published during Tolkien’s lifetime. More informal conversations took place on Tuesday mornings at the Eagle and Child (the “Bird and Baby” as it was known) and was marked by rollicking male laughter and repartee. It was also fascinating to see the critical role Williams, one of the later to join, had on the vitality of this group. When he died, something died among them as well and the gatherings began to dwindle.

We also have briefer portraits of other Inkling members: theatrical producer and Chaucer scholar Nevill Coghill, biographer Lord David Cecil, poet and scholar Adam Fox, the classicist Colin Hardie, and the scholar, who along with Tolkien labored for Lewis’s return to Christian faith, Hugo Dyson. There are others as well, like novelist John Wain, and those not in the circle, but who contributed and were inspired as well, like Dorothy L. Sayers and Sister Penelope Lawson.

The Zaleskis also explore key episodes in the lives of these different figures. Perhaps most striking was Lewis’s debate with Elizabeth Anscombe. The Zaleskis are more nuanced than some, seeing this both as a serious challenge to Lewis’s ideas on Miracles(he later re-wrote portions in response) and yet not as the utterly devastating setback to his apologetics that turned him to writing children’s stories. They observe that he continued to publish numerous articles on apologetic themes and that the greater concern for Lewis was the effect of apologetic argument on the soul of the apologist.

What was most significant to me was the tale of how this informal gathering sparked literary scholarship, literature in a variety of genre, and for Lewis to a greater extent, and others to a lesser, a Christian intellectual presence at Oxford. This did not so much seem by design, but rather the recognition of these men in each other a vision for such things that they fueled and refined through their weekly discussions. I think of other such groups, like the “Clapham Sect” who gathered around William Wilberforce and brought about both religious renewal and social reforms including the abolition of slavery in early nineteenth century England. What particularly marked the Inklings, it seems to me, was a combination of intellectual rigor and personal affection (sometimes tried and tested) that contributed both significant scholarly work (such as Lewis’s preface to Paradise Lost, or Barfield’s work on language and poetic diction) and works of great popular impact.

This is a book to be savored both by Inklings lovers and a newer generation that may wonder about the world that gave us the likes of Lewis and Tolkien. It is sympathetic without indulging in hagiography. It is real about the shortcomings of the principle Inklings without descending into a hatchet job on their lives. In it we see mere humans (and some mere Christians) whose fellowship birthed an ethos and enduring works that have touched the lives of many.

Editor’s Note: Thank-you to Bob Trube for sharing his reviews with Emerging Scholars! Bob first posted the above review on Bob on Books. The INKLINGS reminded of the importance of engaging in dialog with fellow believers regarding one’s work. With whom do you regularly and/or periodically meet for encouragement, sharing of ideas/drafts, etc? If you don’t have such a fellowship, join or gather one for the coming year. ~ Thomas B. Grosh IV, Associate Director, Emerging Scholars Network

Bob Trube is Associate Director of Faculty Ministry and Director of the Emerging Scholars Network. He blogs on books regularly at bobonbooks.com. He resides in Columbus, Ohio, with Marilyn and enjoys reading, gardening, choral singing, and plein air painting.

Leave a Reply