Rick Mattson, InterVarsity staff and author of How Faith Is Like Skydiving: And Other Memorable Images for Dialogue with Seekers and Skeptics(InterVarsity Press, 2014), continues his series. Rick will be speaking at Urbana in a seminar called “Love Your Atheist Neighbor,” and he’s giving us a preview here. Read Part 1. Interested in doing a series on Urbana or an interview with an Urbana speaker? Email us here.

Responding to the Science-only Objection

In my prior post I replied to the question, Who is my atheist neighbor?, by suggesting that he/she is a friend to serve, an author to read, an enemy to love.

In any of these cases it’s common to hear the “scientific objection” to Christian faith, as made to me by Jonathan, an atheistic engineering student in Chicago:

“Science is rational and based on reason. Faith is just the opposite. It’s basically irrational. So unless God proves himself to me scientifically, I’ll never believe in him.”

How might we reply to Jonathan? Of many possible ways, here are two:

Response 1. The demand for scientific proof of God’s existence is not science per se but simply a philosophical preference.

Had I pointed this out to Jonathan (which I didn’t) he might have honestly admitted that yes, proof is an extremely high standard to meet. And while proof isn’t possible or necessary in many areas of life, when it comes to the question of God it’s the only thing he, Jonathan, would accept.

This seems reasonable because our friend is simply being autobiographical. He’s giving a personal preference for proof in a certain segment of life.

But as the conversation unfolded, that’s not what Jonathan said to me. Rather, he insisted that his was a scientific worldview, meaning that all of life is under the domain of science and its rigorous methodology.

This is a huge and unsustainable claim. Does his mother love him? Will he be safe walking home this evening? Is his memory of childhood events accurate? Does he truly have “free will”? None of the answers to these questions (and many others) are provable by the scientific method. Yet he lives as if the questions are, in fact, settled beyond doubt.

So the inconsistent application of the scientific method across one’s whole experience is something to point out. But even more basic is the notion that the demand for scientific proof is not, strictly speaking, practicing science. It can’t be measured for mass or velocity or other physical properties. It’s simply a philosophical preference.

Response 2. Science is helpful in finding God because it studies nature, which is a reflection of God’s glory. But by itself science is an insufficient tool.

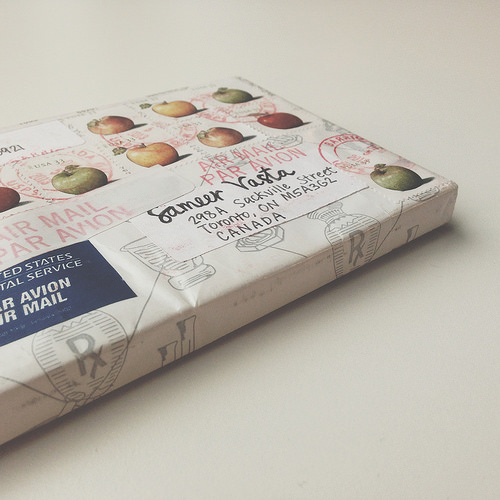

To illustrate, let’s say that in order to receive packages at my house I cut a two-inch opening in my front door, and I instruct the FedEX, USPS and UPS drivers to slip all my parcels through the slot.

Imagine the many deliveries I’d miss, simply for being too narrow minded.

This is, in fact, what I pointed out to Jonathan. I said that we need to come to God on his terms, not our own — and that God was under no obligation to play by our rules. He is God and we are not. So if we create a two-inch slot in our lives which is called the scientific method, we’ll miss out on much of God’s self-disclosure.

Wouldn’t it be better to open ourselves more widely to the ways in which God might reveal himself? Let God define the terms of engagement? Expand our narrow expectations?

So the transaction between ourselves and God is at least partly a matter of the will on our part — the willingness to drop our guard, widen our mail slots and accept God’s methods rather than trying to force him into our own. When we allow God to make the rules of divine-human interaction, we are likely to find him.

The engineer’s reply.

Jonathan the engineer thought about my challenge to exchange the scientific method for a broader band of receptivity. Unfortunately he was not willing to be surprised by God. He held firmly to his system of finding truth, restricted as it was. And if God would not submit to that system, God does not exist. Period.

But wait, I say, not so fast. Maybe this isn’t the end of Jonathan’s inquiry. I’ve learned not to give up on anyone. Sometimes the outlook of skeptics—even those who are “science-only”—changes with time. That’s what happened to my atheist friend Alan. When I asked him what finally turned his thinking after so many years of skepticism, he replied, “Admitting my pride. Yes, the arguments for God were important, but it was ego that blocked the way. When my pride came down it cleared a path for my faith to emerge.”

Jonathan’s reasons for disbelieving may be different than Alan’s. In any case I pray that someday Jonathan will open himself more widely to the possibility of finding God.

Rick Mattson is a national evangelist and apologist for InterVarsity, speaking at over eighty campuses the past few years. He lives in St. Paul, MN with his family. He studied at Bethel Seminary of St. Paul, MN, where he received his masters in the philosophy of religion. As part of his current duties he serves as evangelism coach for graduate students at several universities. Rick’s a committed family man and serious golfer. He is the author of three books: Faith is Like Skydiving, Faith Unexpected and Witness in the Academy.

I think I understand what you’re trying to say – that there are areas of knowledge beyond naturalistic observation. However, I don’t think Jonathan or many others familiar with the scientific method will agree that you cannot apply the scientific method to the examples you provided. You can gather evidence to support your conclusion that your mother does/does not love you. You can take data on your previous walks home and on tonight’s walk home and come to a statistical prediction. You can examine your childhood memories and gather evidence of others’ experiences and come to some conclusion about what may have actually happened.

I think this may point out a misunderstanding of Jonathan’s viewpoint: he’s not living his life looking for indisputable proof of absolute truth – he’s living his life based on the evidence he’s found so far. It’s an evidence-based worldview, not a worldview that requires absolute, immutable truth. Scientists (and scientifically minded) people are often fairly comfortable with a lack of absolute truth, because we are excited by the continual learning process and the promise of future discovery. So we can comfortably say “the evidence seems to point to X, so we believe X is true at this time. Next year we may have new evidence that changes our working assumptions.” We have learned to accept uncertainty, the unknown, and the willingness to change directions in light of new information.

Hi M, Unless I am missing your point, I think we agree. The basic principles of science can be used in most areas of life to gather evidence and draw conclusions — and, as you mention, there are areas of knowledge beyond naturalistic observation (sources might be rational reflection, intuition, testimony, and revelation).

Jonathan, however, was restricting all possible knowledge of God to the scientific method, and he was requiring absolute proof. This seems different than the fair-minded scientist you are describing.

So, what would constitute scientific evidence of God? Steven Pinker, in his review of Jerry Coyne’s recent book “Faith vs Fact” (http://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(15)00743-5.pdf), offered several possibilities. One was this: “A

bright light might appear in the heavens one day and a man clad in white robe and sandals, supported by winged angels, could descend from the sky, give sight to the blind, and resurrect the dead.”

Pinker’s a smart guy. Surely he must know that he has basically described Jesus, right? I’ve heard others go through the same thought process, trying to figure out what would convince them God exists and more or less describing Jesus. And yet, Jesus himself doesn’t seem to count, presumably because he didn’t come heal the blind while we were watching. We have to rely on someone else’s testimony.

That might seem counter to the empirical nature of science, but relying on someone else’s testimony is fundamental to how science is practiced. Most scientists accept that quantum mechanics accurately describes the world, although few have done the math or conducted an experiment on the more esoteric elements like entanglement. Every year, we construct the flu vaccine relying on the fact that ferret antibodies are the best way to test similarities between viruses. That protocol was developed decades ago; at this point, we rely on the testimony of the scientists who published it. Now, granted, in theory that and many other results could be retested, but in practice we don’t do that as often as you might expect. Thus relying on the published testimonies of eyewitnesses to the ministry of Jesus is not as far removed from the practice of science as it might appear.

It’s easy to find lots of examples online by googling “atheist what evidence would convince you god exists.” http://lmgtfy.com/?q=atheist+what+evidence+would+convince+you+god+exists

Greta Christina has a very good answer to the question of “what evidence would you need”: magic writing in the sky, correct prophecies in sacred texts, accurate information gained during near-death experiences, followers of one religion being much more successful than followers of other faiths.

http://www.alternet.org/story/147424/6_(unlikely)_developments_that_could_convince_this_atheist_to_believe_in_god

That’s based on this famous list of evidence that would convince (and a list of things that are not convincing):

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/daylightatheism/essays/the-theists-guide-to-converting-atheists/

RHE did an “interview with an atheist” that gives a lot of insight on this topic. In particular, Hemant The Friendly Atheist replied to this very question this way:

“what evidence or experience (if any) would cause you to believe in God?

At this point, I’d have to experience a miracle that had no natural explanation (and couldn’t possibly have one). A real miracle, too, not “God opened up this parking spot for me; it’s a miracle!” Sometimes, I’ll hear about how doctors couldn’t cure someone’s disease but it “miraculously” went away and it never takes into account that there could have been a misdiagnosis in the first place or that your body healed in a way we just haven’t figured out yet. That’s not evidence of god. Give me something irrefutable.

Or maybe god just needs to talk to me. God loooooooves talking to people who are already Christians, but he apparently hates talking to atheists 🙂 I’m always listening. I always hear nothing.”

In the intro he also said this:

“What keeps me an atheist? Continued lack of evidence for the supernatural. Whenever Christians want to convince me god exists, they cite some personal anecdote as if your cancer went away because God Did It (and not a doctor) or you met your significant other because of God’s Guiding Hand (and not via match.com or through mutual friends or pure coincidence).

In my experience, Christians tend to be very bad at explaining their reasons for why god exists (and specifically the Christian version of god) in a way that any atheist can take seriously. Usually, we can respond with a perfectly natural explanation for your “miracle.” Or, sometimes, I hear a Christian offer their explanation, and I wonder how they would feel if someone from a different faith said the exact same thing. Are they wrong?”

http://rachelheldevans.com/blog/ask-an-atheist-response

M, I do think there’s a difference between 1) What it would take to convince an atheist (such as Hemant) and 2) What God actually provides by way of self-disclosure.

It seems to me the call of all every human being is to submit heart, mind and will to #2.

If I may summarize #2: God’s general revelation in nature (Romans 1) and conscience (Romans 2); God’s special revelation in Christ, Scripture and the Church; and the testimony and case-making of caring (hopefully) Christians. Assuming an informed atheist has access to these disclosures, she is free to accept them or not.

But I think it is presumptuous of the “clay” to expect the Potter to meet the demands of #1. We see something of this Potter/clay relationship played out in Romans 9 on a different topic — divine judgment and mercy. But the principle of who sets the terms of engagement between the two is the same.

If you already accept the existence of a god and accept Christianity as the true religion, then this argument makes sense. But if you look at it from the outside, it sounds like this:

1. A god exists, loves you, and wants to have a relationship with you

2. This god is the Christian God and only reveals himself through the Bible, Christians, nature, and in your own brain

a. The Bible doesn’t look any more ‘divine’ than any other supposedly ‘divine’ books; its inconsistencies and support of very unholy, unloving practices looks anything but ‘godly’

b. Subjective evidence of Christians’ testimony isn’t any more convincing than the subjective evidence of non-Christians’ testimony, and there’s no evidence that Christians are any more moral, healthy, or better off in any way than any other religious or non-religious group

c. Nature is beautiful and amazing but also disordered and full of destruction, death, and suffering

d. Your brain doesn’t seem to have this supposed ‘impression of god’ on it

4. Too bad, that’s all you’re going to get, our God doesn’t care enough (? or isn’t powerful enough?) to show Himself in a way that will make sense to you

5. He made you this way, so I guess he doesn’t want you to know him? and if we’re talking about a more traditional Christian God, he not only made you in such a way that you can’t understand him, but he’s going to send you to hell for that

So I should come running into the arms of this inept, unconvincing, unloving God?