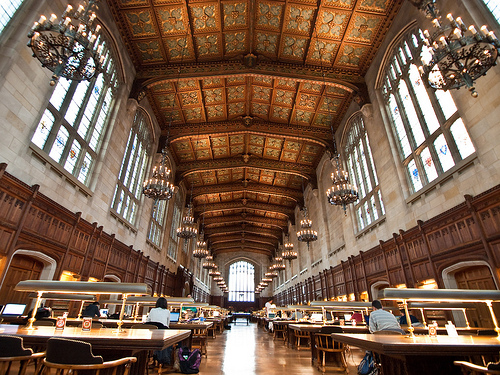

Picture: University of Michigan Law School Reading Room

Rick Mattson, InterVarsity staff and author of How Faith Is Like Skydiving: And Other Memorable Images for Dialogue with Seekers and Skeptics (InterVarsity Press, 2014), continues his series. Rick will be speaking at Urbana Student Missions Conference (December 27-31) in a seminar called “Love Your Atheist Neighbor,” and he’s giving us a preview here. Read Part 1 and Part 2. Interested in doing a series on Urbana or an interview with an Urbana speaker? Email us here.

Making Your Case

In my first post I encouraged you to love your atheist neighbor regardless of whether he/she is friend or foe.

And for atheists who present themselves as “science-only,” I suggested in my second post that science is a helpful—but by itself overly narrow—method for finding God.

The next question that needs to be addressed, then, is How does one find God? This moves us into positive case-making for Christian faith.

A stair-step diagram: One day I was invited by a philosophy professor at South Texas College to present an overview of Christianity in his Survey of Religions class. I happened to be traveling in the area so he enlisted me as a more native speaker of the faith than himself. On a massive whiteboard in the classroom, I drew an ascending staircase of arguments from bottom left to top right. On each step I wrote a word or phrase that summarized an argument, such as origins, design, the historical Jesus, experience, morality and consciousness. And I explained each argument along the way.

The structure of the staircase showed in graphic form the idea of one argument building on another to strengthen the overall case. At the top of the staircase, which was the conclusion of the argument, I wrote a word nobody in the room expected. Instead of the word “proof” I wrote the word convincing. After all, I was playing the role of religious attorney, attempting to convince the jury of students and professor in front of me that the best explanation for reality as we know it is Christian theism. Not proof. Just a persuasive case.

Cumulative case. The approach to argumentation just mentioned is known as a cumulative case. And it is a powerful—but not quick—way to present Christianity to a thoughtful seeker or skeptic.

In his massive Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, Douglas Groothuis lays out a multi-faceted argument for Christianity that moves from classic theistic arguments to intelligent design, morality, religious experience, consciousness, and the reliability of the Bible. The point is that the aggregate effect of these individual elements, what theologian James Beilby calls “a series of converging arguments,” adds up to a sturdy case for Christianity.

A helpful analogy is a civil court of law, where an attorney marshals together evidence such as witnesses, phone records, motives and the like, in order to convince a jury of her thesis. At the end of the day the jury must ask, What’s the best overall explanation of the facts as we know them?, and deliver its verdict accordingly.

The atheist objects. A common response from atheists to the cumulative case is that it functions like a series of leaky buckets, none of which “really holds water.” And if none of the individual containers is leak-proof, says the atheist, it’s unlikely the whole lot fares any better.

But atheists often focus too much on the individual pieces and not enough on the collective strength of the evidence. Let’s say we’re able to present six solid but imperfect arguments that reinforce each other and all point in the same direction—toward the truth of Christian theism. Taken as a whole, the atheist should consider the combined strength of all pieces, even if the individual parts (buckets) contain small leaks.

An example is the case for the life of Jesus as presented in the four Gospel accounts. Christians can provide very good historical reasons to trust the Gospel records by considering the authors, their motives, and the nature of the records. To summarize,

- first-century Palestinian Jews were strict monotheists and wouldn’t invent deity figures such as Christ and the Holy Spirit.

- Nor would they include humiliating material in their stories, such as their own failure to stay awake in the garden of Gethsemane or playing second fiddle to the women at the empty tomb.

- The apostles would not risk their lives for a known fabrication.

- Matthew, Mark, Luke and John provide us with multiple voices of agreement regarding Jesus, yet contain enough differences to be credible.

- Early non-Christian sources plus

- quality NT manuscript evidence add further weight to the case, so that a thoughtful, open-minded inquirer could be readily persuaded to embrace the Jesus of the Gospels.

Notice what just happened. I provided a six-part cumulative case (summarized) for the historical Jesus. But an entrenched skeptic could give alternative explanations for each piece of the puzzle:

- There was a band of polytheistic Jews in Palestine we simply don’t know about—a holdover from OT Jewish apostasy, and they invented Jesus and the Holy Spirit.

- The authors included instances of self-abasement in order to exalt Jesus by way of contrast with themselves.

- The disciples believed the opportunity for religious power outweighed the danger to their own lives.

- Multiple voices (the four Gospels) all telling the same lie represent an even greater lie.

- Early non-Christian sources about Jesus have been tampered with or are otherwise unreliable.

- The abundant NT manuscripts are copies of the original misinformation and thus get us nowhere.

Again, notice what just happened. From the skeptic’s perspective, the six-part cumulative case is recast as six leaky buckets.

So who’s right, the purveyor of the cumulative case or the skeptic?

Dismissibility. Recently I was sitting at a restaurant with one of my atheist pals. Lee is an ex-pastor and an outspoken critic of Christianity. He asked me, as he has dozens of times in the past, what real evidence there is for Christianity. His contention is that there’s not much. I presented in summary form the cumulative case mentioned above, and he responded with the leaky bucket analogy.

Many atheists like Lee dismiss any and all arguments for Christianity because they fall short of proof (the buckets have leaks). This I readily admit. There are no proof-positive arguments that I know of. But if everything we say about God is potentially dismissible, what is the real state of Christian argumentation? Is “dismissibility” a liability? I’ll address that question in my next post.

Suggested resources:

Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, by Douglas Groothius

Echoes of a Voice: We are not Alone, by James Sire

A Jigsaw Guide to Making Sense of the World, by Alex McLellan

Why Christian Faith Still Makes Sense: A Response to Contemporary Challenges, by C. Stephen Evans

Rick Mattson is a national evangelist and apologist for InterVarsity, speaking at over eighty campuses the past few years. He lives in St. Paul, MN with his family. He studied at Bethel Seminary of St. Paul, MN, where he received his masters in the philosophy of religion. As part of his current duties he serves as evangelism coach for graduate students at several universities. Rick’s a committed family man and serious golfer. He is the author of three books: Faith is Like Skydiving, Faith Unexpected and Witness in the Academy.

I don’t think finding leaks in your buckets means your arguments are necessarily wrong, but it also doesn’t mean non-Christians (not just atheists) are fixated on the details and can’t see the forest for the trees. They’re just saying your “cumulative case” is not convincing. Just like you, they’re not requiring absolute proof, just a convincing case – and they’re finding it less than convincing.

What do you do with the fact that proponents of other religions make the exact same “cumulative case” which they find entirely convincing? Are you convinced by their “cumulative case” as well, or do you reject it for similar reasons as your non-Christian friends reject yours? Is the fact that Mohammed and his disciples did (and still do) risk their lives proof that Islam must be true? A 7th-century Arab wouldn’t make up being a prophet, and the similarities between the Koran and the Bible and other historical/theological documents prove its authenticity, so a thoughtful, open-minded inquirer should be readily persuaded to embrace Islam, right? Plenty of people make such arguments, and I’m betting you don’t buy it (http://lmgtfy.com/?q=proof+that+islam+is+the+right+religion)

Since Joseph Smith and his followers willingly risked their lives, does that mean Mormonism is true? A 19th century American would never make up receiving a revelation from God, right? And the similarities between the Book of Mormon, the Bible, and other texts are thoroughly convincing, aren’t they? If you don’t think so, are you not being a “thoughtful, open-minded inquirer” because you’re just fixating on the holes in the Mormons’ leaky buckets? (http://lmgtfy.com/?q=proof+that+mormonism+is+true)

Hi M, You are a thoughtful critic, which I appreciate. If I may respond . . .

You say: “They’re just saying your “cumulative case” is not convincing. Just like you, they’re not requiring absolute proof, just a convincing case – and they’re finding it less than convincing.”

But many people do require proof. I enjoy the privilege of traveling to college campuses around the country — more than 50, the last five years — and I can tell you that I FREQUENTLY hear from nonChristians the demand for proof. Example: an atheist philosophy professor that I debated at UM Duluth. For him, it is proof or nothing. But of course I never make the claim to have proof. Thus the expectations of many nonChristians and the cumulative case (CC) that I provide do not match up. But I can’t help that. I can’t change their expectations.

For those who don’t require proof and who find my CC (not mine, of course; the Christian community’s case, of which I am a spokesman) “less than convincing,” what more can be said? Many people come to faith in Christ based on the CC. Others don’t. That’s how it is with God. He gives us a choice to join the family — or not. Those who find the case for faith convincing will join, those who don’t, won’t.

Sorry if I am missing your point here, M. I do not mean to be evasive or difficult. Please clarify if I have misunderstood you.

You ask: “What do you do with the fact that proponents of other religions make the exact same “cumulative case” which they find entirely convincing?”

But they don’t make the “exact same” CC. To illustrate, in a civil court of law both sides are making their own CC (preponderance of evidence, inference to best explanation, etc.) to the jury. But that doesn’t mean both cases are “exactly the same.” One is more convincing to a jury than the other. That’s the whole point — one CC competes with another. One has more to offer than the other.

You say: “Are you convinced by their “cumulative case” as well, or do you reject it for similar reasons as your non-Christian friends reject yours?”

Precisely. Their CC is not convincing to me. If it were, I would change religions.

(Note that not all non-Christians reject the CC for Christianity. Some find it persuasive and place their faith in Jesus.)

You ask: “Is the fact that Mohammed and his disciples did (and still do) risk their lives proof that Islam must be true?

Reply: No. It only shows that they believed it to be true, that they believed it was not a fabrication. The fairly small claim about the disciples of Jesus being willing to die for their faith is that they would not have done so had they known it to be a fabrication.

You say: “A 7th-century Arab wouldn’t make up being a prophet, and the similarities between the Koran and the Bible and other historical/theological documents prove its authenticity,”

Reply: Sorry, I’m not following you here. Similarities between these religious texts prove the Koran’s authenticity? In what way?

You say: “so a thoughtful, open-minded inquirer should be readily persuaded to embrace Islam, right? Plenty of people make such arguments, and I’m betting you don’t buy it.”

M, I would only buy it if I found it convincing. I’m not faulting their methods. You seem to be saying that similarity of method cancels out the method altogether. I’m fine with other religions having a similar method, just as two disputants in a court of law will employ similar methods of case-making. But that doesn’t make them both right. The jury is convinced by one, not the other. It’s the content of the case that counts.

You ask: “Since Joseph Smith and his followers willingly risked their lives, does that mean Mormonism is true?”

Reply: No, same as above regarding Islam. They would only risk their lives if they believed Mormonism to be true. But if they KNEW Mormonism was a fabrication, they wouldn’t risk their lives.

You ask further: “A 19th century American would never make up receiving a revelation from God, right?”

I’m not quite catching your point here. I think you may be trying to establish a connection between Joseph Smith and the disciples of Jesus. Perhaps you’re saying this: Since a 19th c. American could easily make up a revelation about God — a 1st c. Palestinian Jew would also.

That sounds like odd logic to me but, as mentioned, I might be misinterpreting you.

In any case, the Jews just mentioned are thought to have been strict monotheists and thus possessed a built-in disincentive to create deities, whereas the American had no such disincentive (aside from general social pressure) that I know of.

In any case, I should be clear that “willing to die for your faith” is not an argument about the truth of the faith per se — whether Christian, Muslim or Mormon — but about what the followers believed. If they believed it was false, they wouldn’t have died for it. They would only have died for their religion if they THOUGHT it was true. So the whole argument simply focuses on what they believed (not on whether their belief was true).

You say: “And the similarities between the Book of Mormon, the Bible, and other texts are thoroughly convincing, aren’t they? If you don’t think so, are you not being a “thoughtful, open-minded inquirer” because you’re just fixating on the holes in the Mormons’ leaky buckets?

Reply: Much could be said here. I’ll pick one angle: I have heard the case for Mormonism in person and in writing many times, and I can’t think of a single presentation that used a CC approach. A true CC for Christianity is extremely comprehensive — it covers every discipline, every human condition, every field of study. It claims that the aggregate of all the smaller cases fits together like a giant puzzle to solve the meaning of the universe. But Mormons usually just say “read the Book of Mormon and pray about it. Listen to your inner voice . . . If you hear God speaking to you, respond in faith.” In fact, I once asked the former director of the Mormon Institute in Salt Lake City (a lovely person, by the way) how the world came to be, and he really had no answer. It seems to me that a worldview lacking in basic explanatory power isn’t suffering from minor leaks; its defects run all the way to the bottom. But again, if Mormonism DID have explanatory power and the case was both comprehensive and cumulative, I would listen.

Thanks again for writing, M.

What I mean is, from an outsider perspective, this CC *does* sound exactly the same as the CC for Islam, Buddhism, or any other religion: they all make the same claims with the same amount of evidence. Exactly as you find the others’ CC’s unconvincing, it’s easy to see how a non-Christian would find the Christian CC unconvincing for exactly the same reasons.

You can find plenty of studies that show that the CC that a given person will find “most convincing” will, on average, be the one they grew up with/are most surrounded with in their community. From an objective PoV, that’s particularly damning for this kind of argument – it means we’re all just choosing what we were socialized to choose, not that there’s any real, objective truth in our chosen path.