Note: This discussion contains spoilers for Avengers: Age of Ultron; I recommend watching the film first.

I come to praise Joss Whedon, not to bury him. There is much to enjoy about Avengers: Age of Ultron, and it touches on a number of themes worthy of further exploration. Astonishing visuals do a lot of narrative heavy lifting; the action choreography reveals a lot about the characters and their relationships. Consequently, the film has plenty of opportunities to share what’s on its mind. And apparently, that’s God.

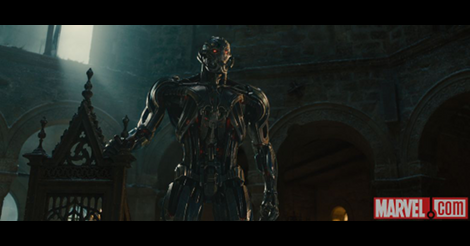

God has a strong presence throughout the film. The titular antagonist, Ultron, lives in a church, quotes the Bible — actually, he quotes God as quoted in the Bible — and appoints himself the ultimate judge of mankind. This self-styled deity also a son who is compassionate and humane, inhabits a body of flesh, and risks his life to save mankind. There’s even a moment where that son, Vision, declares “I am” while the music and editing make sure we don’t miss it.

Christ figures are no stranger to films, so its tempting to read Vision as one, declare the film an endorsement of Christian theology, and be done. I’m not terribly comfortable with that conclusion, though. For one, we are still left with the stereotypical dichotomy of Ultron as the angry Old Testament God and Vision as the loving New Testament God. Furthermore, Ultron himself quotes Jesus (“Upon this rock I will build my church”), so I’m not sure the film wants to be so neatly bisected. Also, both Ultron and Vision are man-made, perhaps implying God is manufactured as well. Most striking is the way Ultron regularly says or does something he regards as human, only to be extremely annoyed to be echoing his creator, perhaps a comment on how often the gods we create wind up seeming so very like us.

Late in the film, Vision observes, in reference to humans, “a thing isn’t beautiful because it lasts.” In my experience, this is a common refrain of secular humanism. Where many religions offer some form of eternal existence, secular humanism embraces the idea that this life is all we get. Where Christians argue that meaning can only derive from that which is eternal, secular humanism regards the finiteness of existence enhances its significance. Hearing Vision express that sentiment, I wonder if we are meant to draw an evolutionary line of development from a wrathful God to a loving God to no God at all.

Now, even though my reading of the film makes me wonder if it has a secular humanist message at its core, that doesn’t diminish my appreciation or endorsement of it. As I’ve discussed previously, I find value in having folks like Joss Whedon, who see the world differently, take the time to express their perspective. We can never hope to engage with people who think differently if we never understand how they think. And in this particular case, I think there is actually a lot in this film we Christians can embrace, rather than only focusing on the places where our theology differs.

To the extent that humanism values humans and human agency, I think there is much to be appreciated about it. Couldn’t we say God is a humanist in that sense? After all, he thought enough of humans to become one of us for a time, and he encourages human collaboration in his plans. In this vein, the sentiment that most reminded me of Jesus actually came from Captain America. (Come to think of it, Captain America had the most explicitly Christian line in Whedon’s first Avengers film: “There’s only one God, ma’am, and I’m pretty sure he doesn’t dress like that.”) The climax of the film involves a rescue attempt to thwart Ultron’s plot for human eradication. There’s a “needs of the many”/”needs of the few” dilemma, but Cap rejects that choice and declares no amount of human loss is acceptable, putting his own life on the line to emphasize the point. Didn’t Jesus risk his own life, and indeed even lose it, to enact his rescue plan for all of humanity?

Also noteworthy is the film’s discussion of evolution. The role of extinction events in evolution is particularly emphasized. Evoking both the story of Noah and the asteroid that may have done in the dinosaurs, Ultron talks about God periodically chucking a rock at the Earth when his creation goes off track. I think this highlights one of the key sticking points in relating evolution and Christian theology. If our theology maintains that there are no coincidences, that God is in control of everything, and if our notion of evolution is one centered on violent death and extinction events, then affirming evolution as natural history yields a rather unflattering picture of God. Obviously, some therefore decide to reject either evolution or Christian theology. That decision is at least partly driven by how the conversation is framed, and a film like this, seen by millions, almost surely plays a part in the framing. I prefer a different approach which reconsiders how we think and talk about God’s will, and how we think and talk about evolution.

While we’re talking evolution, I think the idea that our concept of God is evolving needn’t be dismissed outright. As we noted, it’s overly simplistic to label the Old Testament God as angry and the New Testament God as compassionate; for starters, the Old Testament law shows a lot of concern for the weak and marginalized. At the same time, reading the Bible roughly chronologically, one gets a sense of God’s character being continually revealed. We can try to deny that observation, or we can conclude the whole thing is a human invention. But can’t we also conclude that the language we humans have for talking about God has evolved? This allows us to acknowledge that the way God is described has changed over time, while also affirming the existence of God.

Finally, one of the more intriguing elements of the film is the fact that Tony Stark creates Ultron, sees the problems that result, and then turns around and tries again, which ultimately creates Vision. There is an inclination to accuse Stark of hubris, of playing God, when he creates Ultron; surely then he needs to be redeemed by doing things differently. Yet the film suggests Stark’s sin wasn’t attempting something ambitious, it was believing he could do it himself without accountability. Redemption comes when he acknowledges his need to be engaged in a community; what he creates then is life-affirming. Perhaps this suggests that the more we isolate ourselves, the more we imagine God as someone for us and against everyone else, and the more we interact with others, the more we understand that God is for them too.

Andy has worn many hats in his life. He knows this is a dreadfully clichéd notion, but since it is also literally true he uses it anyway. Among his current metaphorical hats: husband of one wife, father of two teenagers, reader of science fiction and science fact, enthusiast of contemporary symphonic music, and chief science officer. Previous metaphorical hats include: comp bio postdoc, molecular biology grad student, InterVarsity chapter president (that one came with a literal hat), music store clerk, house painter, and mosquito trapper. Among his more unique literal hats: British bobby, captain’s hats (of varying levels of authenticity) of several specific vessels, a deerstalker from 221B Baker St, and a railroad engineer’s cap. His monthly Science in Review is drawn from his weekly Science Corner posts — Wednesdays, 8am (Eastern) on the Emerging Scholars Network Blog. His book Faith across the Multiverse is available from Hendrickson.

“[God] thought enough of humans to become one of us for a time.” I’m at a complete loss as to how Christianity deems itself monotheistic or takes itself seriously with such blasphemous statements like this.

This is such a blatant perversion of the original and absolute monotheism espoused by Abraham and Moses.