May we point to the path, at times narrow and dark, but never without the Light.[i]

Reflection

In the movie Secondhand Lions, Robert Duvall tells Haley Joel Osment’s character:

It don’t matter if it’s true or not. Sometimes you just gotta believe in some things like courage and honor, ’cause that’s what it’s all about.

If truth is up to the individual, then there is no secure foundation for being courageous or honorable. The problem that confronts Secondhand Lions is a pragmatic moralism; if doing good works, it must be right.

Eat, Pray, Love is a movie dedicated to the focal point of life: me, myself, and I. Where else but in a movie can a person leave her job for a year, go find herself in India, and come back to the same well-paid position? The impracticality of the film’s premise is only upstaged by its philosophy of self-fulfillment.

Cider House Rules begins with the premise that we make our own set of laws. Relativism—where ethics become a personal choice—should be the arbiter of decision making. Pleasantville, in a similar vein, questions authority as a whole. If everything is relative and no absolutes exist, individualism becomes the standard of conduct.

Pragmatism, relativism, and individualism are born of certain philosophies—the reason why people do what they do. Acting on my philosophy of life produces certain results. Like it or not, my behavior is premised on my point of view. Movies are dependent upon an outlook of life. Here are five principles which can help form the foundation for a Christian philosophy of film.

Universal Principles Answer Universal Questions[ii]

People everywhere ask, “Why am I here? What’s my purpose in life? What is right and wrong?” God’s answers are the same for all people, places, cultures, and times. Fatherhood is universally accepted as important, as exemplified in movies. The Place Beyond the Pines tells the sad tale of two fathers and two sons and the impact the former has on the latter. A Bronx Tale tells the important story of how impressionable a young boy can be and how his life can be swayed by an older man. Of course, movies like Father of the Bride with Steve Martin and Father of the Bride with Spencer Tracy tug on father/daughter heartstrings. Finding Nemo and Mr. Mom tell dramatically comedic stories of a father’s importance. Film depends on the established roles that God set in Genesis for stable families.

All Truth Is God’s Truth[iii]

Movies are premised upon the universal standards that God has created. Whether acknowledged by humans or not, the world was made and is interpreted by God. Justice, love, comedy, redemption—all stories about life—are based on the way God made His world. Toy Story 3 develops the importance of friendship, maturity, fidelity, loyalty, and stability. Thirteen Conversations About One Thing asks:

What is happiness? Can happiness mean something to one person and something totally different to another? How do we view our happiness in relationship with others?

The Big Kahuna investigates how we communicate with others: do we treat people as people or projects? Relationships, community, and sociology of all kinds depend on truth communicated from heaven to earth. No movie can function without true truth.

The Ministry of Reconciliation[iv]

The Ministry of Reconciliation[iv]

Any movie that contains concepts of redemption or forgiveness is woven with the threads of scriptural truths. God considered all people from every nation as important, calling them to repentance and rejoicing. Even God’s judgments were designed specifically to demonstrate to other nations that “there was no one like Yahweh in all the earth.” Therefore, depending on one’s vocation, all believers can be mediators to the church and the world. The movie Cars asks:

How do we teach children how to reject their own pride? What is important in friendship, and what matters most in life?

Rails and Ties conveys a storyline consumed with human frailty and the courage necessary to meet it. Gran Torino, Clint Eastwood’s work, shows sensitivity toward Christianity that should not be missed. Clint’s symbolic gesture in the climactic scene is a sober moment. We must learn that justice may be won only by sacrificing ourselves. Traumatic tales consider the difficulty of sin and the necessity of reconciliation.

Salt and Light in the World[v]

God’s people are to bring the light of the gospel to others. There is hope for all nations, even in the afterlife. The preservation of, illumination of, and attraction to “true truth” remains the responsibility of believers. Movies like Crash force us to confront our own prejudices while providing us glimpses of Providence, even when we fail to see them. Apocalypto reminds viewers at the outset that “a great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.” Juno wants us to consider that life is precious, even while it may seem peculiar. Shades of pain paint Bella‘s story, yet compassion draws us and compels our viewing. One cannot help but celebrate the wonder of conscience and sacrifice through redemption, whose cost cannot be counted but whose life can be shared through Bella. Movies give us opportunity to point at truth, goodness, or beauty to say, “Look! See!”

Becoming All Things to All People[vi]

The message does not change but the methods may. Even Paul was compelled to make physical alterations so that Timothy might be accepted. The apostle’s modus operandi was to meet people “where they are.” Movies help us rejoice to find ways to identify and to discover ways of communicating truth. Hachi shows us that everyone longs for camaraderie. The film is based on a true story, one recounted in Japan today. Hachi is the dog of legend; a statue is erected in his honor at a Tokyo train station. Frozen River gives motherhood a new definition: the dogged determination to the death that says, “I will provide for my children, no matter what.” Black Snake Moan, a movie confronting terrible circumstances, makes us rely even more upon the sustenance of Scripture and Jesus’ sure salvation. Movies can be the connection that believers long to make with our unbelieving friends.

Philosophy—literally “love of wisdom”—bids us to share heavenly insights, loving our neighbors, through film. Everyone brings this philosophy of life to answer the why questions of any film. Every movie invites us to consider someone’s belief; the response of each Christian should be to compare and contrast it with his or her own. Relativism, individualism, pragmatism, or any other “ism” may present itself before our eyes on the big screen. Knowing what we believe and why we believe it will prompt us to question what we see when the lights go down.[vii]

Questions

- Philosophy answers the why question—what is the meaning, purpose, or reason we do anything? What philosophies give foundation for our thinking about watching movies? How do we answer the question, “Why am I watching movies?”

- What universal principles do we hear people regularly discuss (for example, freedom or compassion)?

- When we watch movies, do we think, “The world should not work that way!” or “I wish life worked out like that all the time!”

- In one way or another, every movie has a moral statement: this is right, or this is wrong. How can we identify the moral statement in the movies we watch?

- How have we engaged our family, neighbors, or coworkers in discussions about movies?

Prayer

Dear Lord. Help me to think biblically about the movies I watch. Help me to understand what philosophies have impacted my thinking in movies. And help me to share your answers to the question “Why?” with others. Amen.

Resource

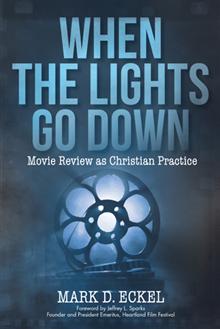

Mark D. Eckel. When the Lights Go Down: Movie Review as Christian Practice. (Westbow, 2014).

[i] From Walker Percy’s book by the same title, taken from “notes for a novel” on the frontice page of his posthumous nonfiction work: “the novelist is more apt to set forth with a stranger in a strange land where the signposts are enigmatic but which he sets out to explore nonetheless.”

[ii] Deuteronomy 4:5-8; Proverbs 11:14; 14:34; 29:18; Daniel 1:3-21; 4:34-37; 6:25-28.

[iii] Psalm 119:152, 160; 1 Kings 3:1-15; 4:29-34; 10:1-9.

[iv] Exodus 19:5, 6; 2 Corinthians 5:17-21. For example, Exodus 9:13-21, Psalms 96-100.

[v] Genesis 12:1-3; Ecclesiastes; Isaiah 42:6; 49:6; Matthew 5:13-16; Acts 28:25-28; Galatians 3:6-9; Philippians 2:15, 16. For example, Isaiah 19; Zechariah 14:16-19; Malachi 1:5.

[vi] 1 Corinthians 9:19-22; Acts 16:1-3; Acts 17:16-34.

[vii] Taken from the section “Philosophy” in Mark Eckel’s book When the Lights Go Down.

Editor’s note: The final piece of Mark Eckel’s five part movies series. What a way to wrap up as many of have spent time watching film over the weekend and plan to do much more over the summer. If you’d enjoy the opportunity to write a review of a movie’s portrayal of higher education, interaction with an important topic with which you are familiar due to your studies/research, and/or value to your campus fellowship (due to a movie night, discussion group, etc.), please drop Thomas B. Grosh IV (Associate Director of the Emerging Scholars Network) a note. He’s very interested in hearing from you this summer 🙂

Dr. Mark Eckel is adjunct professor for various institutions, President of The Comenius Institute (website), spends time with Christian young people in public university (1 minute video), hosts a weekly radio program with diverse groups of guests (1 minute video), interprets culture from a Christian vantage point (1 minute video), teaches weekly at his church (video) and writes weekly at his website warpandwoof.org.

I appreciated your series, although I have seen probably less than 5% of the films you mentioned and have not even heard of 50% of them. For many years (decades) I have avoided movies, except as a distraction on international flights, because most I have seen I either wind up (as a scientist) saying, “that’s impossible” or disagreeing so strongly with the philosophy of the film that it bothers me for days afterwards. The exceptions have been some of the historical dramas, often based on real stories, that show courage in the face of tragedy or problems. It is good to hear that there are still some good films out there.

Gerald, I’m pleased for your good note. Like you, I am “bothered” by a film’s philosophy all the time! One of the reasons we pursue our vocational venues with such passion, I suspect, is because our belief drives us to consider and critique other philosophies and theories. I hope that the book will be of benefit to you and many others throughout the years.