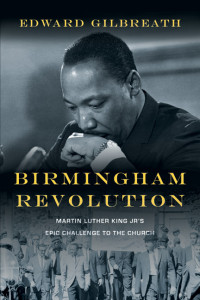

Birmingham Revolution: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Epic Challenge to the Church

Birmingham Revolution: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Epic Challenge to the Church

By Edward Gilbreath

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Solitary confinement in prison can be a shattering psychological experience, one often used to break the spirit of those imprisoned. For Martin Luther King, Jr., solitary confinement served not only to further forge the character of this civil rights leader, but resulted in one of the signature documents of the civil rights movement, indeed, one of the most important human rights documents of the Twentieth century. The document of which I’m speaking is “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

Edward Gilbreath’s new book gives us an account of King’s life centered around the Birmingham Civil Rights demonstrations and this letter that became a kind of manifesto for this movement. Rather than give us another full-blown biography, Gilbreath briefly sketches King’s early life and the tension between coming from an elite Atlanta family of preachers with a distinguished education, and the call to civil rights leadership that began in Montgomery and suffered a setback in Albany, Georgia. King found himself caught in a nexus of caution, gifting, and necessity when Fred Shuttlesworth invited him to Birmingham.

Gilbreath paints the contrast between the cautious but eloquent King and the firebrand activist Pastor Shuttlesworth. Shuttlesworth grasped that King’s visionary leadership was necessary to turn passion into disciplined action. What it also led to were confrontations with police chief Bull Conner who threw King, and eventually hundreds of child-demonstrators into prison. Those confrontations, complete with fire hoses and dogs caught the nation’s attention and began to turn the nation’s support to King.

Meanwhile, a group of eight moderate white clergymen, known to actually have sympathies with the civil rights movement, published an open letter in the Birmingham paper taking issue with the marches led by outsider King, counselling patience, moderation, and local solutions. A prison guard, perhaps to further depress King, gave him a copy of the paper while he was in solitary.

Gilbreath explores the phenomenon of latent black anger at continued injustices as a backdrop to King’s response of scribbling the “letter” in the margins of the newspaper. In it, King makes the argument, later expanded into his book Why We Can’t Wait that makes the case for civil disobedience to unjust laws and that “justice delayed is justice denied.”

The rest of the book considers King’s life after Birmingham and the response of evangelicals then and now to King. Gilbreath does not attempt to cover over the flaws in either King’s theology or life but also explores the blindness of both the eight moderate pastors in Birmingham as well as many in the white evangelical community to the biblical themes that shaped King’s vision in the “Letter” and in his preaching.

The book helped me understand not only the circumstances behind King’s “Letter” but also raised questions for me about our continued racial divides in the United States and my own temptation to identify with the moderate white pastors rather than hear the anger and pain that comes from injustices and the biblical themes that challenge me to see why justice can’t wait.

Thank-you to Bob for sharing Birmingham Revolution: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Epic Challenge to the Church from his blog Bob on Books. Below is Ed Gilbreath — on Your Neighbor (Video: 1 min, 4 sec) and Ed Gilbreath — on The Movement (Video: 59 sec). There is also a study guide made easily accessible on-line through Read Up (Lorraine Caulton, editor. InterVarsity Press, 2013). ~ Thomas B. Grosh IV, Associate Director, Emerging Scholars Network

Bob Trube is a former Associate Director of Faculty Ministry and Director of the Emerging Scholars Network. He blogs on books regularly at bobonbooks.com. He resides in Columbus, Ohio, with Marilyn and enjoys reading, gardening, choral singing, and plein air painting.

Leave a Reply