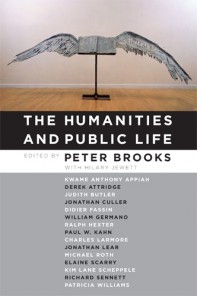

The Humanities and Public Life edited by Peter Brooks with Hilary Jewett (Bronx: Fordham University Press, 2014).

The Humanities and Public Life edited by Peter Brooks with Hilary Jewett (Bronx: Fordham University Press, 2014).

My rating: 3 of 5 stars.

There is no question but that the humanities are under fire. Budgets are being cut, sometimes whole departments. How then to justify the humanities within the university, without accepting “instrumentalization”, a term thrown around much in this book, which means roughly, being able to demonstrate some “deliverable” or bottom line worth.

Peter Brooks, the editor of the book,and organizer of the symposium from which the articles and discussion in this book was drawn, starts with the “Torture Memos”, a series of Justice Department documents from the second Bush administration that justified waterboarding and other forms of torture against detainees deemed to be “dangerous” to national security. Brooks believes this to be the result of poor and unethical reading by those who formulated these memos (an assumption I question), and something that the humanities fundamentally address.

Following his introductory essay which overviews the symposium, Judith Butler talks about the instrumentalization of the humanities and uses as a case in point the term “deliverables”. Her contention ultimately is that the humanities equip one well to deconstruct the use of this term and to engage in resistance to its application to the humanities.

Three panels follow, each with two presentations followed by two or three responses and further discussion. The symposium and book conclude with a general discussion with a number of the presenters and respondents participating.

The first panel explores the question closest to Brooks’ heart, “Is there an ethics of reading?” Both presenters basically say yes, with Elaine Scarry arguing that reading literature and poetry can develop empathy for the human condition. Charles Larmore explores the act of interpretation and taking the author or communicative act serious in how one reads and derives meaning from a work.

The second panel considered the ethics of reading and the professions with Patricia Williams exploring the challenges of the vagaries of words and language that is often overlooked in various “legal fictions”. Ralph Hexter explores similar challenges in the life of a university administrator.

The final panel took on the relation of the humanities to human rights. Jonathan Lear’s essay, perhaps the most eloquent recounts living among the Crow Indians, not as a sociologist but as a story-teller listening to their words. A group that had been studied to death came alive when Lear simply expressed interest in their stories of identity lost and re-established, going so far as to adopt him into the tribe. Paul Kahn considers the broader domain of human rights and the ability of the humanities to interpret the languages of power governments use in human rights discussions, or evasions of those rights.

I was particularly interested in the discussion of ethical reading, something most readers don’t think about, yet which is vital for those who study the works of another and review or criticize those works. Equally, as Brooks and others would maintain, it can represent the vital difference between careful adherence to versus distortion of the law. (And yet I wonder whether those who created the Torture Memos were in fact excellent readers who were looking for ways to deal with the vagaries of words to distort laws to justify their ends. Not ethical, but it may not be for the lack of “ethical reading skills”.)

Much of this had for me the feeling of a “rear guard action”, the tactics of a retreating force. Perhaps at times, the use of critical skills can indeed be used to resist authoritarian, or simply pragmatic forces. This quality, and the often jargon-laden character of presentations hardly seem adequate for a spirited public argument for the place of the humanities in higher education. For that, I might direct the reader to Anthony Kronman’s Education’s End. The title of this work suggested an elevated and challenging public argument but delivered nothing more than a refined academic discussion that seemed to me to offer little to check the erosion of the humanities in either public life or higher education.

(This review is based on an electronic version of this work made available compliments of the publisher through Netgalley.)

Thank-you to Bob for sharing Review: The Humanities and Public Life from his blog Bob on Books (6/9/2014)! In Higher Education Books, Bob notes that he has been reading more on higher education in preparation for an upcoming InterVarsity Christian Fellowship Faculty Ministry Conference he will be directing: The ‘End’ of Higher Education in Twenty-First Century America: Change and the Calling of the Christian Educator (June 21 – 27).

As some of you know, I am very much looking forward to participating in this conference (and seeing some of you there!). Please take a few minutes today and over the course of June 21-27 to pray for

- travel to/from InterVarsity’s Cedar Campus (Upper Peninsula, Michigan) — especially those of us making the journey with a number of kids 🙂

- a rich time of reflection/conversation centered around the Word of God for all those present (faculty, spouses, children . . .)

- insight for program staff and presenters in preparation, delivery of material, personal conversations, and follow-up

- growing clarity on what it means for the people of God to be creatively engaged in higher education

- the sending forth of participants in mission during a complex time of change.

- the further development of a community of conversation through online resources such as the

To God be the glory! ~ Thomas B. Grosh IV, Associate Director, Emerging Scholars Network

Bob Trube is a former Associate Director of Faculty Ministry and Director of the Emerging Scholars Network. He blogs on books regularly at bobonbooks.com. He resides in Columbus, Ohio, with Marilyn and enjoys reading, gardening, choral singing, and plein air painting.

Leave a Reply