“How can you believe in God and science at the same time?”

Even though I am rarely asked this question so plainly, it is often implied in conversation. Many atheistic advocates think that there is a conflict between the two. They may suspect that a belief in the supernatural is used primarily to explain the physical world with non-physical means and to “fill in the gaps” for conundrums for which there is no better or more reasonable determination. They may believe that beliefs are driven by a search for meaning and cohesion, and that this persistent pursuit of Reasons may mistakenly (and somewhat ironically) lead people to become more irrational. They may believe that science, as the ultimate paradigm in methodically inductive, deductive, and reductive Reasoning, is consequently the most obvious arbiter of truth. They may then believe that the willful denial and rejection of conclusions arrived at by science is therefore illogical, irrational, and subsequently idiotic. It is therefore reasonable to see why people would automatically consider those who believe in the supernatural to be willfully ignorant, regarding them with suspicion, condescension, and/or frustration.

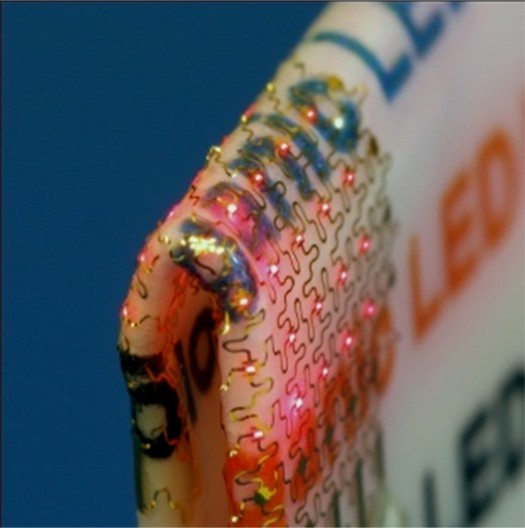

I grew up saturated in both religion and science. My father is an electrical engineer, well accomplished and respected in his field. As a child, I was surrounded by gizmos and textbooks, not understanding what “GaAs Semiconductors” were but curious to find out. His approach to the world has always had the paradigm of a scientist: always thinking, observing, and making his own private conclusions. He had a very strong moral sense, but it was strongly grounded in a Confucian sense of discipline, orderliness, and character virtue. He was not a Christian at the time and he generally took an agnostic and aloof stance towards religion, seeing it as a generally positive force in shaping his family’s sensibilities but still regarding it cautiously. It was almost as if he was wary towards the existence and significance of a God who seemed to be a relatively benign but otherwise untested hypothesis.

My mother is a firm Christian and a nurse, nearly opposite to my father in temperament and belief. Where he is cool and detached, she has been deeply suffused with emotion. Where he sought out natural principles and laws of order in the physical world, society, and human relationships, she has been attuned to spiritual precepts and looks to them as Rea sons why things are what they are. She is diligent and meticulous in this way, always keeping an eye out for them, an ear cocked for the whis per of a con se quence or a les son. Most were sim ple illus tra tions and object lessons of basic char ac ter: an irri tat ing per son was placed in my life to teach me patience; a flat tire the day after a stingy finan cial deci sion was a reminder to be more gen er ous; an unex pected piece of good news was an exam ple of God’s con sis tent good ness. Some links were easy to see and under stand. Oth ers were not.

I grew up lis ten ing to both these nar ra tives, never really seeing a conflict between the two paradigms. They are both internally consistent in their logic. They are both meticulous in assessment and constantly rework the available evidence into a deterministic and causal understanding of the world. I had been taught that, though science could inform much of the “how” of life, only religion could provide the “why” with any degree of functional certainty. I sup posed it was the way in which every one learned to make sense of an oth er wise hap haz ard world, how we main tained the hope to cope through dif fi cult sit u a tions. But as I grew older, rea son began to chal lenge the Reasons.

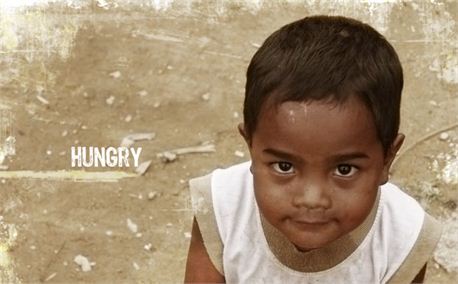

It started with the big ques tions. Were peo ple really poor because they were lazy? Was HIV really God’s pun ish ment to homo sex u als? Was evo lu tion really at odds with Chris tian ity? And of course, the biggest of them all: is there a Rea son for suffering?

For nearly each of these ques tions, I had trouble accepting the answers from my mother. We would go through end less cycles of argu ments, some of which were very heated and charged with bit ter words. Some times I held on to prove a point, but I often found myself fight ing out of sheer stub born ness and pride. I was chal leng ing the Rea sons because I began to doubt that there were any. I was not certain that any amount of goodness truly governed the natural world, and strongly suspected that humanity was alone in its struggle to survive sentiently. This breakdown in faith in the divine, which began in college, blossomed in medical school.

Mad ness and chaos. That was what dis ease seemed to me, the strug gle between life and death in the hos pi tal wards. Kind and gen er ous patients suf fered from hor rific fates while those who were malin ger ing and mali cious fed off of the system’s gen eros ity with out pun ish ment. The hos pi tal was a new and dis ori ent ing place in which the old rules, the old Rea sons (either physical or spiritual) no longer seemed to apply. Who lived and who died was less a func tion of moral ity as it was of bio log i cal processes, state vari ables, and lots of luck. In a world where so much was at stake, only the new rea sons, the Evi dence of hard data and tight cor re la tions mat tered. And yet even there, the most basic assump tions about stan dards of care were chal lenged and occa sion ally over thrown by the lat est and great est stud ies, and many rea son able, long-standing asso ci a tions between health and dis ease once thought to be clinically objective dis in te grated under closer scrutiny.

My own shift in per spec tive was sub tle at first, and I wasn’t able to artic u late my dis com fort with it until one of my friends began using “evi dence based argu ments” for every thing. He would launch into a polit i cal dis cus sion with oth ers and pep per them with the ques tion, “Where’s your ref er ence? Show me the study.” It was an irri tat ing thing for him to do in the con text of oth er wise casual con ver sa tion, but the inflam ma tory nature came from the real iza tion that most of what we say on a daily basis is com pletely speculative. We make con clu sions based on very lit tle evi dence because that is how we must deal with the com plex i ties of daily life, but if we truly real ized how une d u cated and spo radic those deci sions were, we would lose the con fi dence to make it from one moment to the next.

Some thing in me hard ened. My faith in God, the Ulti mate Rea son, which had once been so strong began to set tle for lesser things. God may count the hairs on your head, but I can tell you now that it will be exactly zero once your chemother apy is started. You can pray for a mir a cle, but if we don’t ampu tate that leg tomor row you might lose your life. Pray ing is good, but pray ing 20 hours out side in the snow is not; please restart your bipo lar med ica tions or we won’t let you out.

And so prayer, some thing I once loved to do, became more an act of des per a tion and a super sti tion than one of faith. I didn’t know what to pray for, mainly because I was tired of being dis ap pointed. I began knock ing on wood and cross ing my fin gers because they seemed to be just as effec tive: barely, if at all. I was tired of BS and really just wanted to admit: I don’t know I don’t know I don’t know.

Finally, at the end of a long year in clinical rotations, a collapsed lung (pneumothorax) knocked me out long enough to mull it over in my mind. True to form, my mother insisted that there was a Rea son behind my lung col lapse, that the tim ing, the method, the stresses I was going through were all too coin ci den tal to be due to any thing else. And we talked, per haps for the first time, about what it meant to use rea sons and to look for Rea sons. It reminded me of the Tower of Siloam:

There were some present at that very time who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had min gled with their sac ri fices. And he answered them, “Do you think that these Galileans were worse sin ners than all the other Galileans, because they suf fered in this way? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all like wise per ish. Or those eigh teen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them: do you think that they were worse offend ers than all the oth ers who lived in Jerusalem? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all like wise per ish.” —Luke 13

When ever I talk at length about the nature of suf fer ing, I men tion an exam ple a men tor once used. Suf fer ing is just the push that tips a cup over; it has no bear ing on what comes out. This is what I have come to believe about suf fer ing, ill ness, death, and all Events with con se quences for which we seek a Rea son: they reveal what is inside me, deep down inside that refuses to come out oth er wise. I may have no con trol over my envi ron ment or the insan ity of this small earth we inhabit, but there is always some thing in me that I can ask to have transformed:

Do not be con formed to this world, but be trans formed by the renewal of your mind, that by test ing you may dis cern what is the will of God, what is good and accept able and per fect. —Romans 12

It made me reconsider epistemology, or the study of how we know anything to be true at all. It made me wonder why I should remain decidedly Christian.

[To be continued…]

David graduated from Princeton University with a degree in Electrical Engineering and received his medical degree from Rutgers – Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a Masters in Public Health concentrated in health systems and policy. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at Christiana Care Health System in Delaware. He continues to work in Delaware as a dual Med-Peds hospitalist. Faith-wise, he is decidÂedly Christian, and regarding everything else he will gladly talk your ear off about health policy, the inner city, gadgets, and why Disney’s Frozen is actually a terrible movie.

Leave a Reply