Models

There are perhaps as many models for helping as there are universities in Africa. I hope through this forum to learn more from other readers of the variety of options and discuss what may or may not be effective.

Much of the pioneer work in post-secondary education in Africa was done by starting bible colleges. Faculty were most often not traditional US academics with advanced degrees (apart from seminary degrees). Many of these schools have become universities, but in doing so struggle to attract sufficient master’s and doctoral staff to meet true university accreditation requirements.

At the other extreme, I think that history shows that support of US based graduate training for African academics often ends in brain drain.

Christian (and secular) volunteerism has proved helpful, but some options for Americans with private African universities can waste and abuse short-term and long-term donations of money, talent and time. Short-term and mid-term experiences of inadequately prepared individuals, often facing language barriers and finding students at a level below what they expected does not use resources wisely. Frustration leads to broken relationships, inadequately educated students and damage to the careers of volunteer faculty.

Options that twin partner institutions in the United States with African universities have been particularly prevalent in (secular) medical education. However, American secular universities are not international charities. In many twin programs experienced faculty rarely spend extended periods of their careers teaching in Africa and much of their effort is directed toward supervising visiting American students.

The new Clinton Foundation Human Resources for Health partnership in Rwanda brings health care faculty from leading US universities for up to one year (though faculty can renew). The goal is to create more than 500 medical specialists for Rwanda in the next 7 years. However, it is not clear how senior the full-year visiting faculty are and this partnership is extremely expensive. To learn more click here.

Again in a secular framework, Fulbright scholarships have supported American faculty for up to a year. European governments have done the same, as has the Wellcome Trust. Long term Wellcome Trust grants have added to research in Africa, often training African academics.

One Christian agency placing professors internationally, including within Africa is Global Scholars (http://www.global-scholars.org). They have placed over 230 Christian scholars from over 50 academic disciplines in scores of public universities in 34 nations since 1988. In sub-Saharan Africa these nations include Nigeria, The Gambia, Cameroon, Uganda, Rwanda, Botswana and South Africa. It has not used the team model.

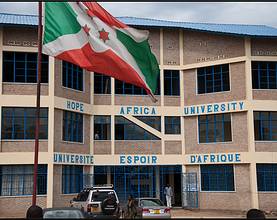

After beginning a program of the twinning type for a secular institution (now established with rotating faculty and trainees), I have decided to explore the longer-term Christian team vision. I am gathering a team for Hope Africa University in Bujumbura, Burundi through World Harvest Mission (www.whmathau.com).

In 2003 Hope Africa University had 110 students. Today it has 5,700 including 300 medical students spread over 6 years and the beginnings of a dental and pharmacy program. The need is great. Most indigenous faculty are adjunct faculty. Burundi is recovering from years of genocide, civil war and the flight of skilled workers. Half of the population is under 16.

In the past, the university has asked for short term professorial help via partner denominations and the American charity, Friends of Hope Africa University (www.haufriends.org). Now it is partnering with World Harvest Mission (www.whm.org) in finding longer-term medical and non-medical faculty. WHM is sending one all-medical team to teach and treat at a remote campus. It is gathering a second medical and non-medical team of expatriate professors to teach at the main campus in the capital (interested parties may apply!).

I encourage readers who know of other successful models to report them in this space. The need to respond is compelling. But we must to do it well. One size will not fit all.

Finally, I would like readers to prayerfully consider their own place in responding to this need.

- Are you willing to help construct an academic environment in American institutions that allows peer academics to respond to this need without making career-ending choices?

- Are you willing to consider spending a portion of your career in Africa?

- Are you financially willing to support those who may be willing to go?

For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich. — 2 Cor 8:9

I know that the Lord secures justice for the poor and upholds the cause of the needy. — Ps 140:12

Dr. Bond is currently in French language school preparing for a new role working under an American NGO providing medical education, pediatric consultation and recruiting professors for Hope Africa University in Bujumbura, Burundi. He and his wife expect to be on site in Bujumbura in early 2014.

Dr. Bond was the Medical Director of the Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center and Professor of Clinical Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati 1999-2012. Prior to this, he held the same positions at the Blue Ridge Poison Center at the University of Virginia 1989-1999

Dr. Bond completed a fellowship in Medical Toxicology at Good Samaritan Hospital/Samaritan Regional Poison Center (now Banner Samaritan) in Phoenix, Arizona. He has practiced pediatric emergency medicine and medical toxicology for over 25 years.

Dr. Bond is a past-president of the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology and a former chair of the American Board of Medical Specialties’ examination sub-board in the specialty of Medical Toxicology. He has served as an Associate Editor (for Toxicology) of the Annals of Emergency Medicine and is on the editorial board of Clinical Toxicology. Dr. Bond was awarded the 2012 Louis Roche Lecture by the European Association of Poison Centres and Clinical Toxicologists, its highest honor. His topic was the Underappreciated Problem of Pediatric Medication Errors in the Developing World.

Dr. Bond has authored more than 50 toxicology articles or chapters and delivered more than 100 major toxicology lectures in the United States and 30 around the world. His particular career interests have been in pediatric poisoning injury, acetaminophen toxicity and the epidemiology of drug abuse. He has participated in the training of more than a score of toxicology and pediatric emergency medicine fellows and innumerable residents.

Dr. Bond has long been interested in international medicine. In 1985-1986 he served as the sole doctor for a rural area of Kenya with a population of 30,000-50,000. He has lectured to physicians throughout the world. He serves on the board of World Harvest Mission, an NGO with health related work in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan. He has assisted the World Health Organization (WHO) in developing rural triage criteria for pediatric hydrocarbon exposure and pediatric pesticide exposure. He has served the WHO as an onsite trainer of physicians and other health care workers at the site of the outbreak of severe pediatric lead poisoning in northern Nigeria. In 2012, he pioneered a long-term on-site presence for Cincinnati Children’s Hospital at Kamuzu Central Hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi. As a result, that work is funded through 2017.

In terms of other models, the London Mathematical Society, together with the African Mathematics Millennium Science Initiative, have a current call for research mentors from UK institutions. Details here: http://www.lms.ac.uk/grants/mentoring-african-research-mathematics

Thank you for including the thoughts about “career-ending choices”. As a former overseas volunteer, I know that the threat of this danger is quite real and can prevent terms of service.

Hi Randall, thanks for your follow-up post.

Westerners must indeed do this well if their involvement is to be anything more than dubious (colonial history being what it is).

The various one-year placements you refer to above are surely not an unqualified disaster, but the limitations of this timeframe are severe and, in my experience, the very nature of a short-term visit hampers our ability to actually appreciate these limitations.

But perhaps we can at least say, frankly, that short-term visits are the most bare-bones response possible.

And, as interested Westerners, we surely need to be prepared to offer more than the minimum, to ask What is best? and — if indeed we are endeavouring to approach this as servants — to consider that question from a local perspective.

To put this another way: the fact that an African university is making an open-handed invitation and is endeavouring to promote Western-style education does not either qualify the need for long-term visits, or justify the existence of short-term visits.

So here’s a question: what makes “long term”? I want to pose this as an open question — I can only speak from the experience of my own backing organisation, which considers 6 years as the normal timeframe to become settled and responsive in an intercultural setting.

Your question is partly rhetorical but I do not think the barriers are so high as to preclude effective participation for less than (for example) 6 years. Others may have different ideas and I invite more responses. My goal has been to broaden the view of mission careers to include academics—serving for any duration–where Africans are asking for help. Every situation has risks—for both parties. My hope is that more will be humbly willing to accept the risks, knowing we have a sovereign God.

For life on life impact there is nothing like a long-term life on life relationship. You may be right about the length of time for forming friendships, effectively participating in the life of the department/university/society/church as an equal.

Within any specific invitation, however, many issues are interwoven. One must consider:

1) Who determines the need—the inviting institution or the expatriate? It must be the host.

2) What is the nature (servant heart) of the individual expatriate—how receptive is that expatriate to learning and submitting to the ways of the host culture? What is their past experience? Who will screen them?

3) Are those expatriates entering with the hope/expectation of being replaced by one of their students? How quickly could that happen?

4) What is the nature of the work? A specific surgical technique may be demonstrated and taught in a relatively short period of time. That example is a way of saying the degree to which the requested work is content or technique heavy as opposed to relationship, general knowledge or teaching skill heavy certainly will matter. In my, limited, experience, African requests for academics tend to reflect this distinction (and the competition for talent) with greatest requests in medical fields, science and engineering and business. What is the institution recruiting the expatriate to do that can’t be done locally without them? How important is that need for the needs of the university or the society? [Note that here host governments and host institutions may have competing priorities.]

5) How well are the “wheels greased” by prior relationships at an expatriate institution to host institution level? How experienced are expatriate peers and host institution peers at receiving and integrating new expatriates?

6) I am sure there are a host of neglected issues I will leave to others to bring up.

Circumstances are different in every environment but to the extent that hosts are asking for help, we need to prayerfully consider how to respond.