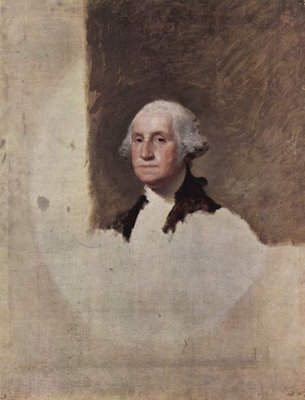

The assistant rector at Christ Church in Philadelphia, the Reverend James Abercrombie, once preached a vehement sermon protesting the “unhappy tendency of’those in elevated stations who invariably turned their backs upon the celebration of the Lord’s Supper.” Though Abercrombie did not name names, then President George Washington, who was in attendance that day, took the message to be aimed directly at him and thought it “a very just reproof.” Washington’s custom had long been to excuse himself from church when it came time to partake of the sacraments and he now realized that by so doing he had deeply offended his fellow congregants. Thus, Washington resolved from then on to skip church altogether on Sacrament Sundays (Holmes, pp. 63-4).

So, no, George Washington was not an orthodox Christian in any conventional or historic sense. Though he never went so far as to take scissors to the Bible the way Thomas Jefferson did, his faith was clearly a predictable sort of Deism with no room for the miraculous, much less the sacramental. In his letters to churches, for instance, he wrote in typical Deist-speak, variously referring to “Providence,” “the Deity,” “the Grand Architect,” and the like, but never to, say, the divinity of Jesus or the Holy Spirit.

Similarly, James Madison abandoned orthodox Christianity for Deism while in his twenties and John Adams was a Unitarian (bordering on Deism) who denied the existence of the Trinity and the divinity of Christ. There were, of course, sincere orthodox Christians among the Founding Fathers, like Patrick Henry (who, it should be remembered, sharply opposed ratifying the Constitution) and Samuel Adams (who historically was much better at brewing trouble than beer). But orthodox Christians were by no means either the most numerous or the most prominent members of the Founders.

Quickly surveying the faiths of the Founding Fathers, one cannot help but wonder how anyone ever got the idea that America was founded as “a Christian nation.” Perhaps it is because we tend to associate the colonials of our land with the deeply Protestant Pilgrims, in celebration of whose first harvest we glut ourselves each November. But, of course, we forget that Jamestown, a purely commercial colony, had been established several years before the Pilgrims sought religious refuge on these shores. We forget, too, that the Puritanism of the Pilgrims in Massachusetts was an Indian-slaughtering, witch-burning, Baptist-beating, Quaker-branding form of Christianity, far removed from the religiously tolerant spirit of the Founding Fathers, and hardly a form of faith we would like to reinstate.

As a former middle school history teacher, I often find myself ruminating on such things on the week of July 4th. To be honest, I love Independence Day and I am a pretty patriotic person. I love my country. But I have never understood the whole “Christian America” thing. Thus, this week I have found myself wondering about what sorts of challenges Christian historians might face in a contemporary American evangelical church setting. To get at some answers I called up my longtime friend Wen Reagan, who is finishing up a PhD in American Religion at Duke University. Wen is also a graduate of Duke Divinity School and is the worship leader at a local church.

So, Wen, given the prevalence of the whole “Christian America” ideology in American churches today, what has been your experience in the church as a historian of American religion? How do you navigate conversations about America’s history in church? Well, it hasn’t really come up all that often for me in church. For one thing, I never have to deal with it from the leadership because the leadership at my church has been very intentional about not conflating nationalism with Christianity. They’ve been really good about that. But it does come up within the congregation sometimes.

And what are those conversations like? Generally, they’re not really conversations. They’re usually just comments. The first thing you need to understand is that I’m not really seen as an authority —most people in my congregation do not see me as a scholar or as an academic at all. In part that’s because they see me primarily as their worship leader, which makes sense. But it’s also because I’m at Duke, which, in my denominational context, is often viewed with suspicion as a liberal or secular institution. So in this sense, my education often is already suspect.

Do you think things might be different if you were coming out of one of your denomination’s seminaries? Maybe. I suspect I might be acknowledged as a scholar if they trusted the school where I was trained and trusted me to give the “right” answers. But I think it’s a deeper problem than that. More important is the fact that we don’t really talk about American church history at all in my church context. I mean, we’ve tried to do a few Sunday school classes on the Reformation here and there but. . . .

And did you teach those? No, the elders taught those. Are any of the elders historians? No, not by training, but they do a good job for what it is. They’re all really educated people —though their education isn’t necessarily in the humanities. But they do their homework. But, no, they didn’t ask me to teach those classes.

So, wait, your church has offered Church history classes, but they didn’t ask the guy in the congregation who is getting a PhD in Church history at a top-tier school to teach them? That is really interesting. Sure. In my experience, scholars are not really tapped to be resources for the church, even when the church is talking about a scholar’s specialization. Many of our congregants have been trying to think through ways to use the scholars in the congregation: Having the scientists teach some classes on faith and science, and so on. We’re in a university town and we have a lot of PhD students in the church. But those conversations have not moved into the realm of practice.

Why do you think that is? I think a big part of it is the pedagogical stance that the church typically takes. We designate a teacher to come to the congregation and say, “I have knowledge and now I am going to give it to you.” And that’s what people are used to. It’s not Socratic. There’s little room for ambiguity or push-back. As a result, congregants aren’t encouraged to ask and wrestle with tough questions during Sunday school. But for scholars, particularly in the humanities, that’s our world. We’re used to things being complicated and to answers not being so clear-cut. That’s also how we teach, which can be a problem if the goal of the church class is to extract knowledge that can then be clearly and precisely applied to life.

How, then, do you understand your vocation as a Christian scholar, as an American historian within the church? I think scholars have the beautiful burden of helping people to embrace and grapple with the complexity and messiness of the world. History is messy. But that bothers a lot of people because they think that if history is messy, it’s not useful. Utility has a really high value in evangelicalism. We basically tell ourselves the “Christian America” story because it’s useful —it’s a political tool. It allows us to paint people we disagree with as deviating from what it means to be an American and thus, in a sense, what it means to be Christian. But it’s also comforting because we think it can give us a clear roadmap to the will of God, and thus we can interpret God’s will, even speak for God, from history.

But history doesn’t really work that way. It’s a humbling, overwhelming enterprise. It’s complex and can’t be boiled down to a few talking points. It’s not black and white. I mean, sure, in some ways our country is “less Christian” than it used to be. That’s true. But in other ways it’s “more Christian.” We outlawed slavery, right? So which do you go with? The reality is that it’s both more and less “Christian” than it used to be. But it’s this complexity, this nuance, that’s often missing from the church’s historical approach. Before we can even attempt to theologically interpret American history, we need to consider the messiness of its story. Good exegesis requires context. We need to embrace the contingencies that have shaped American Christianity so that we can listen to what the dead have to tell us.

In any case, I agree that history —when done right —is quite useful, even though it’s messy. But it’s not useful because it shows us the will of God. It’s useful because it gives us glimpses of who we are, where we’ve come from and all the competing forces, habits, and ideologies that make us tick. It shows us that we and those that have gone before us are walking contradictions. We cannot plumb the deep, dark depths of history to capture and declare God’s will. We see through a glass darkly, even when we look backwards. We can’t always know precisely what happened and we don’t have access to exactly what God thinks about it. But that’s reality. It’s complicated. And it’s messy. And that’s ok.

Anyways, I think that’s the job of Christian scholars in the church: We have the burden of bringing the church the gift of reality with all of its messiness. Whether the church wants that gift is another question. The Church has to be willing to sit in the danger of hearing what they weren’t prepared for and of having unanswered questions. That’s a posture that is naturally uncomfortable and thus has to be cultivated, and as scholars, I think that’s worth our time and effort.

We probably could have talked for a few more hours at least, but neither of us had time for that this week. But, as usual, Wen gave me a lot to think about. It strikes me that the “beautiful burden” Wen spoke of, the task of helping people to embrace the world’s messiness, is incarnational at its heart. In the Incarnation, God the Son took on all the messiness of a human nature, entering a very complex world through all of the blood, sweat, and feces of a mammalian birth, in order to embrace the world’s messiness and ours. In that way, the scholar’s task —the historian’s task, at any rate —within the Church is to help their congregations to come to terms with our creaturely contingency and with all that that entails, and to resist the temptation of oversimplification.

If you are a Christian scholar, what sorts of creative, practical ways have you found to be a blessing to your church qua scholar? What sorts of unexpected challenges have you met?

Be sure to check out the Emerging Scholars Network Blog series based on Vinoth Ramachandra’s lecture on engaging the university for more insights and ideas on how to bridge the gap between the scholars’ vocation and the life of the church.

David Williams serves part-time as an InterVarsity/Link staff on loan to the Oxford Pastorate, an independent evangelical chaplaincy that ministers to graduate students at the University of Oxford. He is currently pursuing his doctorate in Christian Ethics at the University of Oxford, writing on Friedrich Schleiermacher’s, John Henry Newman’s, and Abraham Kuyper’s divergent theologies of higher education and their potential applications to the modern research university. Before moving to England, David served for five years with InterVarsity’s Graduate & Faculty ministries at New York University. David resides in Oxford, England with his wife Alissa and son Charlie.

“In my experience, scholars are not really tapped to be resources for the church, even when the church is talking about a scholar’s specialization.”

I think this is a really interesting point, and hits the nail on the head in describing the practices of many churches. I think this often stems from the fact that many people think that scholars in specialized fields have been brainwashed or biased to an extent that they cannot offer an objective analysis of the subject at hand, which is extremely unfortunate.

Another problem that I see is that we as scholars are not often good at “translating” the jargon or methodology of our field so that it is accessible to others. It’s often frustrating as a scientist to see research picked up and taken out of context by the news media (NPR had a great piece on the debate over the vaccine/autism link last week).

It would be great to see more Christians in academia reach out and invite others into their work and vocation in order to wrestle with these big issues, including the messiness of history and the beautiful intricacy in the details of how our bodies function and fight disease.

Sorry to take so long to respond, Kelly!

“I think [churches not trusting scholars] often stems from the fact that many people think that scholars in specialized fields have been brainwashed or biased to an extent that they cannot offer an objective analysis of the subject at hand, which is extremely unfortunate.”

So true! The trouble is that this habit of prejudicially dismissing specialists as “brainwashed” allows us to acquiesce in our confirmation biases without ever having to engage arguments or evidence. The logic of it is obviously fallacious, too:

“You believe in evolution? Ha! That’s only because you’re a brainwashed biologist.”

“You believe in systemic injustices? Ha! That’s only because you’re a brainwashed sociologist.”

“You believe 2+2=4? Ha! That’s only because you’re a brainwashed mathematician.”…