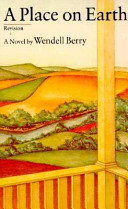

The main character of Wendell Berry’s A Place on Earth, as in many of his novels, is the fictional town of Port William, Kentucky. While Berry is a masterful storyteller, the narrative is less important than the relationships that the characters have with each other, with the town and surrounding farmland they inhabit, and with the land itself.

Berry continually returns to the question of what effect a character has on the people, town, and land around him. When a character is introduced, Berry will often describe the condition of the person’s farm, home, or workplace. For example, Berry contrasts the relatively wealthy Roger Merchant with Roger’s tenant Gideon Crop. Roger inherited a large, profitable farm from his father, but has allowed it to fall into disuse; even Roger’s rental income is handled mostly by his lawyer. Gideon, meanwhile, inherited almost nothing from his father except a tenant relationship with Roger. What little Gideon has, however, is well-maintained and attended to. In Berry’s vision of the world, your stewardship of your home and workplace is a moral dimension of your character. It’s not the complete judgment, but it’s important.

Relationships are also part of this stewardship. One of Roger’s few friends —perhaps his only friend —is Mat Feltner, one of the heroes of Berry’s universe. Mat describes his friendship with Roger as “perplexing,” because Roger regularly calls on Mat for his counsel, keeps Mat engaged in long, rambling, over-complicated discussions of minor issues, and never takes Mat’s advice. Despite this frustrating pattern, Mat still invests time and care in his relationship with Roger. Mat’s attitude toward Roger, in many ways, mirrors his attitude towards farming: care, hard work, and good stewardship are their own rewards, regardless of the outcome.

Campus as a Place on Earth

As I have been reading A Place on Earth, two comparisons have come to mind. The first is the campus as a place made up of a combination of land, people, and relationships. In Berry’s novels, the history of an individual or a family is never far from the surface, and he will often interrupt the narrative with a back story that gives deeper meaning to the immediate situation. Isn’t it so often the case on campus that we can’t understand what’s happening without knowing the history that has led up to this moment?

Campus ministers newly arrived to a university are often at a great disadvantage when dealing with faculty because of their lack of history. Undergraduates don’t know the history either, so they and the campus minister are working from the same place of ignorance. Faculty, on the other hand, have often been on the campus for a long time and have deep memories of the place. Like the good stewards in Berry’s novels, good faculty are concerned for the long-term health of their campus. A brand-new campus minister is an unknown factor. Is this person going to give to the campus or merely take from it? Does this campus minister love the campus as much as I do?

Voting as Shallow Stewardship

Today, of course, is Election Day in the United States. My Twitter and Facebook streams have been inundated with friends and strangers telling me to vote. For months, I’ve been hearing about how important this vote will be, how much my vote counts (or doesn’t count), how our side (whichever that might be) has to get out the vote, et cetera, et cetera.

Here’s the thing, though: voting is about the smallest thing you can do to contribute to the well-being of your community. It’s important, for sure, and I vote in every election —national, state, and local. But the act of voting, and even the political process that it’s part of, is only one element of civic life.

Berry often refers to the membership of Port William, meaning the people who make up the town and the relationships between them. In many organizations, including churches and our nation (if “membership” is extended to include citizenship), voting is the right of members. However, it’s only one part of being a member, and there’s a danger in attributing too much importance to it.

At my former church, there was a guy who showed up at every annual meeting and debated point after point of the budget and annual report. He would stand up and raise a question every few minutes, making sure his voice was heard before every vote. I can’t tell you this guy’s name, because I never saw him except at the annual meeting. I’m sure he attended church regularly, but I never saw him volunteering, teaching, helping with worship, serving as an usher, or doing anything at church, other than debating points at the annual meeting and making sure his vote counted. He was certainly a member of the church in the sense required by our by-laws, but he was not a part of the membership as Berry uses the term.

Membership in Community

Regardless of how the vote turns out today, I hope that your vote is only the beginning of your involvement in your community. I also hope that you view your role on campus as that of a good steward, working to contribute to the place rather than simply taking what you need.

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

- How you seen campus history impact the lives of faculty, students, and campus ministers?

- What’s your sense of the role of voting in civic and community life? How important is it?

- Do you think the campus is a membership in the same way as a small town or church?

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

Great post, Mike! I think one of the hardest things about being a good steward on campus is that college campuses tend to be transient places for a lot of people. If you’re a faculty or staff member you may be there for years, but if you’re in undergrad or even graduate school there’s often a strong sense that you won’t be there forever.

It’s hard to invest in a place that is only sort of yours. I wish I’d paid more attention to the place itself and its virtues when I was in graduate school. It’s hard to do that with all the time pressures, but I could have done simple things, like rotating where I studied between coffee shops I wanted to support, local libraries, nearby parks when the weather was good, etc. I’ve found paying more attention to places makes me more able to invest in them when simple opportunities arise – the local library is looking for $5 pledges toward a project, the special collections at my own school has a comic book exhibit that my undergrad class would love, and so forth.

I’d love to hear other people’s thoughts on investing well in a place that might seem temporary.