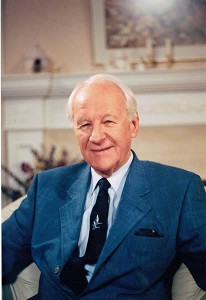

Last week, John Stott went to be with the Lord. As an author, theologian, and working pastor, few people have had as large an influence on evangelical Christianity around the world over the past 100 years. Fittingly, his death came during the IFES World Assembly, a global gathering of evangelical university ministries, symbolic of Rev. Stott’s lifelong passions for the Gospel, the university, and global Christianity.

FYI: I’ve listed a collection of obituaries and remembrances of John Stott’s life at the bottom of this post. If you’ve seen other good ones, please link to them in the comments, and I’ll update the list as I’m able.

Perhaps one of the more surprising appreciations came from NY Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, who titled his appreciation “Evangelicals Without Blowhards”. I read Kristof’s column shortly after it was published, but science professor RJS, writing at Scot McKnight’s Jesus Creed blog, caused me to take a second look at it this morning. Kristof praises two things in particular about John Stott: his thoughtfulness and his compassion.

Mr. Stott didn’t preach fire and brimstone on a Christian television network. He was a humble scholar whose 50-odd books counseled Christians to emulate the life of Jesus —especially his concern for the poor and oppressed —and confront social ills like racial oppression and environmental pollution.

A bit later, he writes:

Mr. Stott, who was a brilliant student at Cambridge, also underscored that faith and intellect needn’t be at odds.

RJS notes that there are many, many other evangelicals who exemplify this kind of intellectual rigor. Though the focus of her post isn’t social activism, she highlights Kristof’s concern for deeds done. Here’s Kristof again:

Evangelicals are disproportionately likely to donate 10 percent of their incomes to charities, mostly church-related. More important, go [sic] to the front lines, at home or abroad, in the battles against hunger, malaria, prison rape, obstetric fistula, human trafficking or genocide, and some of the bravest people you meet are evangelical Christians (or conservative Catholics, similar in many ways) who truly live their faith.

Isn’t this a bit of an odd pairing: intellectualism and activism? Academics are often criticized for living in “the ivory tower” as opposed to “the real world,” which I think is a bit unfair. Aren’t classrooms real? Aren’t laboratories real? In some ways, academic researchers are more invested in “the real world” than virtually anyone else. The ESN lunch group at Ohio State includes several entomologists, who know far more about the insects who live in my own home and yard than I do.

The “Bookish” Intellectual

Still, the distinction is being drawn between the pragmatic and the intellectual, and that’s a real distinction. Several months ago, I took the Strong Interest Inventory, which organizes types of work into six categories, based on decades of research, known as Holland Codes. Academics tend to be Investigative and “Artistic” (creative) in this system, which also means, in this system, that they tend to pull away from the Enterprising and “Conventional” (organizational) categories. Interestingly, in this system, academics are also close to the Social and Realistic (“doer”) categories. It’s not that academics aren’t “people persons” or dislike “hands on” type of work, but their approaches to these areas will look different than, say, a gifted entrepreneur or community organizer.

There’s also an introversion/extroversion dynamic at work. As Adam McHugh points out in Introverts in the Church, evangelical churches value extroverts as leaders and ministers, even though there’s nothing more inherently spiritual —or even leadenly —about extroversion. My colleague Jeff Gissing, in his appreciation for Stott, noted how he appreciated Stott’s “bookish” personality”:

He is one of the handful of pastors who I look to as a role model of being a pastor without being a corporate CEO type, or a salesman, or a politician. I work in a study not an office. I aspire to be a working theologian.

Beyond personality, though, rigorous academic study requires long periods of reflection and analysis. I often joke with graduate students that, if you aren’t an introvert when you start your PhD, you’ll be one by the time you end. One of my favorite scenes from the show The Big Bang Theory involves two physicists who need to “buckle down and work.” The song “Eye of Tiger” starts playing, which was made famous in Rocky III and now stereotypically accompanies video montages of athletic training or hard work. In this case, though, the joke is that the physicists’ hard work consists of’staring at a blackboard for hours on end and thinking. It really is hard work, though of a much different kind than Rocky’s.

Typically, whatever you practice, you’ll get better at doing, while those skills you don’t practice will stagnate. It only makes sense that, if becoming an academic requires long periods of solitary mental work, you’ll get better at that, to the detriment of other kinds of abilities.

The “Activist” Evangelical

Unlike the culture of the academy, though, the culture of evangelical Christianity greatly values pragmatic, activist work. One of the classic hallmarks of evangelical Christianity is its activist streak. Historian David Bebbington defined evangelical Christianity by four defining qualities, the last of which is:

activism, the belief that the gospel needs to be expressed in effort

In this month’s Christianity Today, David Neff interviews Mark Noll about his new book, Jesus Christ and the Life of Mind. Noll is probably best know for writing The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, in which he critiques the anti-intellectual tendencies within evangelicalism. (The interview is not yet online.) Noll makes this important point about evangelical Christianity:

Almost everything in the evangelical world that undercuts serious and sober thinking actually plays a productive role in some other aspect of evangelical life. I never wanted [in Scandal] to make a categorical statement that thinking is the most important thing. But it is important.

If you’re an evangelical academic, you’re already standing between two cultures with radically different sets of values’before we even get to questions of religion and ultimate meaning.

The Bookish, Activist Intellectual Evangelical

However, what kind of activist was John Stott? Let’s go back to Kristof’s praise for evangelical Christians:

Evangelicals’go to the front lines, at home or abroad, in the battles against hunger, malaria, prison rape, obstetric fistula, human trafficking or genocide’ (emphasis added)

I didn’t know Rev. Stott, and I’m not as familiar with his life, writings, and work as many of my colleagues, but this strikes me as a terribly misleading way of describing Stott’s own work. He was indeed “on the front lines,” but in a very different manner. Here’s one description of Stott’s “front lines” work looked like, from John Stackhouse, who relied on Stott to help him through a particularly difficult summer of manual labor when he was a college student:

To stay sane-literally-I made myself read Stott’s Christian Counterculture [published in the US as The Message of the Sermon on the Mount], his exposition of the Sermon on the Mount-for twenty minutes each morning before work. It got me started and directed for the day.

Stott was also famous for personally helping young ministry leaders from around the world, as described in Neff’s article “The Man Who Wouldn’t Be Bishop.” As you might expected, Stott’s “personal touch” took his own particular slant:

David Gitari, the now-retired Anglican archbishop of Kenya, experienced Stott’s focus in a more puzzling way. In Portraits of a Radical Disciple, Gitari tells of his days as a theology student at Tyndale Hall, Bristol. Stott invited him to stay in his London rectory (nicknamed “The Wreckage” or “The Stottery” by some). “I was at the Stottery for one full month, and to my surprise I met my host only once!” Gitari writes. Stott rose early, breakfasted alone, then went about his pastoral duties or locked himself in his study.

I don’t know how to resolve the tension between evangelicalism’s emphasis on action and the academy’s emphasis on reflection. Frankly, I’m not sure that we should resolve this tension. If nothing else, the tension pushes us toward a rhythm of inward and outward movement encouraged by many spiritual formation traditions. The tension also gives us an outsider’s perspective on both the church and the academy, which keeps us from getting too comfortable in either sphere.

Can intellectuals also be activists? Nicholas Kristof thinks so, as do I. What does “intellectual activism” look like? That’s a question for another day, but the life of John Stott gives us a good starting point.

What are your thoughts on the tension between the intellectual and activist life? How do you understand and work through the tension in your life?

The Life of Rev. John Stott

- John Stott Memorial site

- NY Times obituary

- Christianity Today obituary and special section

- Andy Le Peau and IVP

- John Stackhouse

- Jeff Gissing

- Scot McKnight, who also collected remembrances

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

I don’t have time right now to write a thoughtful response, but I do want to say thanks for this good post! Good things to think about here.

The tension of action versus reflection is one I feel keenly as a writer, and even more keenly when I’m traveling. I don’t want to “waste” a minute of my time in another culture, but in order to understand what I’ve seen and experienced and in order to write about it, I must necessarily pull out of it into a room somewhere shut away from the place I’m there to experience and learn.

Kami, Thank-you for articulating the tension of traveling-writing. I’m experiencing that right now as I’m at a regional staff conference with some ‘must finish’ tasks on my place but such a beautiful place to have conversations with God, colleagues and family. As such, must run 🙂 Time with God first.