Yesterday, USA Today published an opinion column by University of Chicago professor Jerry Coyne called “Science and religion aren’t friends.” Coyne, the author of Why Evolution Is True, opposes any attempt to reconcile, integrate, or otherwise bridge the gap between science and religion. To Coyne, religion is less than worthless:

…pretending that faith and science are equally valid ways of finding truth not only weakens our concept of truth, it also gives religion an undeserved authority that does the world no good. For it is faith’s certainty that it has a grasp on truth, combined with its inability to actually find it, that produces things such as the oppression of women and gays, opposition to stem cell research and euthanasia, attacks on science, denial of contraception for birth control and AIDS prevention, sexual repression, and of course all those wars, suicide bombings and religious persecutions. [Emphasis added.]

I’ve not read anything by Coyne except for this op-ed article, but it’s apparent that he greatly values truth – “true truth” as Francis Schaeffer would have called it. Throughout the op-ed, Coyne contrasts scientific and religious understandings of truth:

Science operates by using evidence and reason. Doubt is prized, authority rejected. No finding is deemed “true” —a notion that’s always provisional —unless it’s repeated and verified by others. We scientists are always asking ourselves, “How can I find out whether I’m wrong?” I can think of dozens of potential observations, for instance —one is a billion-year-old ape fossil —that would convince me that evolution didn’t happen.

[Several paragraphs later]

And this leads to the biggest problem with religious “truth”: There’s no way of knowing whether it’s true. I’ve never met a Christian, for instance, who has been able to tell me what observations about the universe would make him abandon his beliefs in God and Jesus. (I would have thought that the Holocaust could do it, but apparently not.) There is no horror, no amount of evil in the world, that a true believer can’t rationalize as consistent with a loving God. It’s the ultimate way of fooling yourself. But how can you be sure you’re right if you can’t tell whether you’re wrong? [Emphases added.]

I won’t address the question of whether Coyne’s description of how science works is accurate —except to suggest that it might not be. Instead, I want to address this common claim that, because religious claims are not falsifiable, they are therefore meaningless.

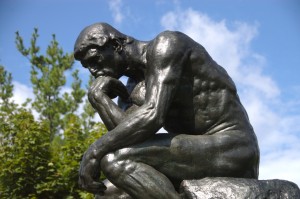

Photo credit: steven n fettig via Flickr

First, the concept of falsifiability is more complex than Coyne suggests. Back in the spring, at the 2010 Stone-Campbell Journal Conference, Richard Knopp of Lincoln Christian University delivered a paper on “The Relevance of the Philosophy of Science for Christian Faith” —I don’t think it’s online anywhere, but I wish I could link to it because Knopp offered an excellent review of 20th century philosophy of science debates as they relate to Christian belief. Instead, I’ll point you to Alvin Plantinga’s “Naturalism Defeated” (PDF) and other works related to the concept of warrant. Unfortunately, Coyne’s editorial follows a trend of proponents of atheism working with philosophy that’s about 75 years behind the times. Novelty is not a virtue in itself; however, to write as if no one has ever answered or even considered these ideas is surely an academic vice. (And, of course, Plantinga’s ideas have also been challenged by other philosophers.)

OK —let’s leave philosophy behind and get to something I’m more comfortable and familiar with: American religious trends. Coyne claims that no Christian has ever been able to tell him “what observations about the universe would make him abandon his beliefs in God and Jesus.” Coyne contradicts himself in his very essay: he claims that he was formerly a religious believer, so surely there must be something that can convince religious believers that they’re mistaken.

Indeed, millions of Americans have found things that convince them to change their religious beliefs. This is a common occurrence in American society. Allow me to cite the ever useful Pew Forum U.S. Religious Landscape Survey, which made religious transience one of its major themes in 2008:

More than one-quarter of American adults (28%) have left the faith in which they were raised in favor of another religion – or no religion at all. If change in affiliation from one type of Protestantism to another is included, 44% of adults have either switched religious affiliation, moved from being unaffiliated with any religion to being affiliated with a particular faith, or dropped any connection to a specific religious tradition altogether. [Emphasis added]

Read the full report on Changes in American Religious Affiliation (PDF). It’s fascinating stuff.

If Coyne is right —that there is literally nothing that can convince a religious believer that he is mistaken —then why are people changing religious affiliations (or abandoning them altogether)? Is it random? A product of sociology? Changes made for economic benefit? For example, a religious young person seeking a career as a university scientist would probably have an easier career path if he embraced atheism (a choice which seems to mirror Coyne’s own story).

Or could there be something else? Could Coyne’s definitions of knowledge and truth be too narrow —or even mistaken at their very core? Even in science, there are many claims which are either impossible to prove/disprove (e.g. speculations about what “must” have happened millions of years ago in the evolution of the human brain) or claims which could be theoretically proven, but whose proofs are turning out to be so difficult that it may very well turn out to be practically impossible (e.g. the Higgs boson).

If someone were to interview Americans about their religious beliefs, I suspect that one would find all sorts of different reasons for their conversions —some based on evidence, some of relationships, some based on pure reasoning, and many, many more.

For me, it was the realization that Jesus of Nazareth knew more about how to live than I did and a subsequent decision to follow his ideas wherever they led. About a year later, I decided to ask my girlfriend Elizabeth to marry me, based on my enjoyment of her company and the optimistic conclusion that it would be better to be married to her than not (among other factors). My decisions in these matters were not scientific, but does that mean that they were wrongly made? I have only one life to live, so far as I know – how could I possibly attain a scientifically acceptable standard of repetition and verification to confirm these decisions?

I’d suggest that a better way of understanding science is that it is a specialized form of investigation constructed for a specific set of purposes, not the standard by which all other aspects of life are measured.

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

Updated to include link to Coyne’s original column. [October 13, 2010 at 1:52 PM]

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

I like your response, Micheal. Particularly your challenge to Science’s claims to authority over all universes of knowledge. I suspect a full response would require a similar categorization of religious or relational knowledge. Of course, i long for an overarching epistemology that can hold various avenues of knowledge together in healthy tensions and relationships. Perhaps Gadamer, Lonnergan? my knowledge of these two is certainly less than yours…

Thanks, David. I wish I knew more about Gadamer and Lonnergan – my knowledge consists of Everett Hamner telling me I should read some Gadamer.

And it was “science’s” acceptance of eugenics that led the Holocaust. Before anyone condemns faith as the cause of evil, one needs to understand power, and how power can appropriate any system of knowledge.

Coyne’s arguments also bring to mind a counter-argument that is commonly made within cultural anthropology. I’m reminded of discussion of fatal granary collapses by the anthropologist Evans-Pritchard in his book WITCHCRAFT ORACLES AND MAGIC AMONG THE AZANDE (pp. 69-70). Granaries provide shade, so sometimes a person is sitting underneath a granary when it collapses. Evans-Pritchard states that the Azande accept the explanation that old granaries collapse due to structural weaknesses caused by termite damage, but that the Azande astutely point out that this explanation is not sufficient to explain why a particular granary collapses the moment somebody is sitting underneath it. That, they say, can only be explained by witchcraft. On page 73, E-P states “Zande belief in witchcraft in no way contradicts empirical knowledge of cause and effect.”

As a way of knowing, science deals poorly with what it elides as “coincidences.” Zande beliefs in witchcraft provide a valid (in the logical sense) explanation of coincidences while accepting empirical knowledge of cause and effect. This means Zande beliefs provide an epistemological foundation to explain more about our world than Western science. So should we all, including Coyne, accept Zande beliefs?

No, but I will point out that about a decade after publishing WITCHCRAFT ORACLES AND MAGIC AMONG THE AZANDE, E-P professed his faith in Christ and joined the Catholic Church in England.

Interesting Micheal, thanks!

Two quick thoughts… first, Christianity IS falsifiable… as Paul relates in 1 Corinthians 15, if Christ did not rise from the dead, it’s all completely worthless. E.g., if they ‘found the body’ or Christ and his death/resurrection was somehow proved to be a hoax, Christianity would be finished.

Second, on what is “scientific” and what is “unscientific”, Meyer and Laudan and others have cogently argued that these terms today are more emotive and perjorative and generally useless. (e.g. http://www.discovery.org/a/3524 )

What is more important, as you alluded to, is truth. Whether or not something is ‘scientific’, is it true?

Another important point to consider here is that those who believe science is superior to religion with respect to knowledge need to give some sort of argument for this, and when they do so, they are making use of philosophical knowledge and argument. When the door is opened to philosophical argumentation, then all sorts of arguments can be made about the veracity of religious claims.

That’s a good point, Mike. It reminds me of C. S. Lewis’s observation (among others) that, as soon as one starts to claim that one action or way of life is “better” than another, you’ve entered the world of moral absolutes (since “better” implies a standard by which the actions ought to be judged), which then leads in all sorts of interesting directions.