Here on the ESN blog, we’ve often blogged about differing views of education, particularly the conflict between education as personal formation and education as professional training. I encountered these differing views in two articles recently. I expected to see competing visions of education to make an appearance in a column on faculty as role models for students, but it was a bit of surprise to find them in a light (so I thought) opinion piece on the “books for boys” genre.

First, the expected: last week, Inside Higher Ed published a column by Lee University’s Kevin Brown, under the unfortunate title Lacking the Mission(ary) Zeal. I say “unfortunate” because Lee is a Christian college, and the reference to missionaries only confused matters. The column actually addresses the mission of a university. Brown compares and contrasts his own university’s stated mission with that of four nearby secular institutions, focusing on universities’ vision for student formation and the role of faculty in that formation.

The conventional wisdom states that universities mostly gave up their in loco parentis role over the past few decades. Brown found that universities’ mission statements told a much different story.

However, out of the four institutions, three of them also mention some aspect of students’ lives that goes well beyond the idea of academic training and moves into the area of changing their lives in some rather drastic ways. The community college, for example, says that it will “enhance quality of life, and encourage civic involvement,” while the state university will “prepare students to lead lives of personal integrity and civic responsibility in a global society,” “conduct research, teaching, and outreach to improve human and animal medicine and health,” and “contribute to improving the quality of life.” Here at Lee, in addition to the spiritual goals we have for students, we hope to foster “healthy physical, mental, social, cultural and spiritual development.” Only the private institution does not go beyond the basic academic goals in its mission and values.

Brown’s next two paragraphs are key, but I won’t reproduce them here in order to keep this post from just becoming a long quotation. Read the full column instead. Brown makes two points worth considering:

- Most professors assume they have little direct role in the personal formation of students.

- Yet professors constantly attempt to shape their students’ lives and beliefs in all sorts of ways, sometimes quite radically.

We’re now in the same territory as Stanley Fish’s Save the World on Your Own Time.

The second place I encountered these contrasting visions of education was wholly unexpected: a Wall Street Journal column on gross-out books for boys. Thomas Spence, who runs a conservative publishing house, notes the growing gap in literacy between girls and boys, and observes that common tactics for getting boys to read —”gross” books like SweetFarts or reward systems that “bribe” boys with video game time —are counter-productive and ineffective. Here’s where the column took a turn I didn’t expect. Spence cites Aristotle, Plato, and C. S. Lewis on education as the “formation of manners and taste,” then writes:

One obvious problem with the SweetFarts philosophy of education is that it is more suited to producing a generation of barbarians and morons than to raising the sort of men who make good husbands, fathers and professionals. If you keep meeting a boy where he is, he doesn’t go very far.

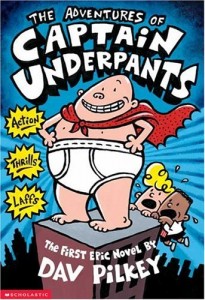

As the father of a young boy, this makes sense to me. As a parent who reads out loud to his children, I also would prefer to read Kidnapped than Captain Underpants. (Though I was also convinced by Michael Chabon’s Manhood for Amateurs that children need literature and other entertainments that don’t meet their parents’ approval.)

I won’t try to draw too many connections between these two articles, except to ask:

If personal formation begins in childhood and extends into our adult years, what’s the proper role of educators in the formation of their students?

The former Associate Director for the Emerging Scholars Network, Micheal lives in Cincinnati with his wife and three children and works as a web manager for a national storage and organization company. He writes about work, vocation, and finding meaning in what you do at No Small Actors.

As a prof in English, I am concerned by the lack of basic reading skills my students have… let alone the lack of critical thinking skills they have with regards to moral issues. For instance, today, I can’t say I was very surprised that a number of my 250+ freshmen were “upset” to learn that “Little Red Riding Hood” is a story about rape, just as Disney’s “Beauty & the Beast” is a positive depiction of battery… because a whole bunch of those students could not even spell the word “raip” or “baitery”… Sad.

Michael, you raise a point that may be part of the problem here… that kids are encouraged to read “anything” as “long as they are reading”… Or answer “anything” as “long as they are participating” or take “any courses” as “long as they complete the degree” etc..

Indeed, our university also has a mission statement/vision which they plaster on everything recently… but such visionary statements aside, their bottom line is still “as long as student enrollments are on the rise” and “as long as money comes rolling in”…

Mediocrity, market-place mentality, as-long-as- assembly-line-production, call it what you will, but it certainly ain’t zeal.